NASA Data Points To Why Some Exoplanets Are Getting Smaller

NASA data points to why some exoplanets are getting smaller and also losing their atmospheres. In a new study using NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, scientists think they may have found out why this is happening.

Author:Rhyley CarneyReviewer:Paula M. GrahamNov 17, 20233.9K Shares62.4K Views

NASA data points to why some exoplanets are getting smallerand also losing their atmospheres. In a new studyusing NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, scientists think they may have found out why this is happening. It seems that the inner cores of these planets are pushing their atmospheres away, causing them to shrink.

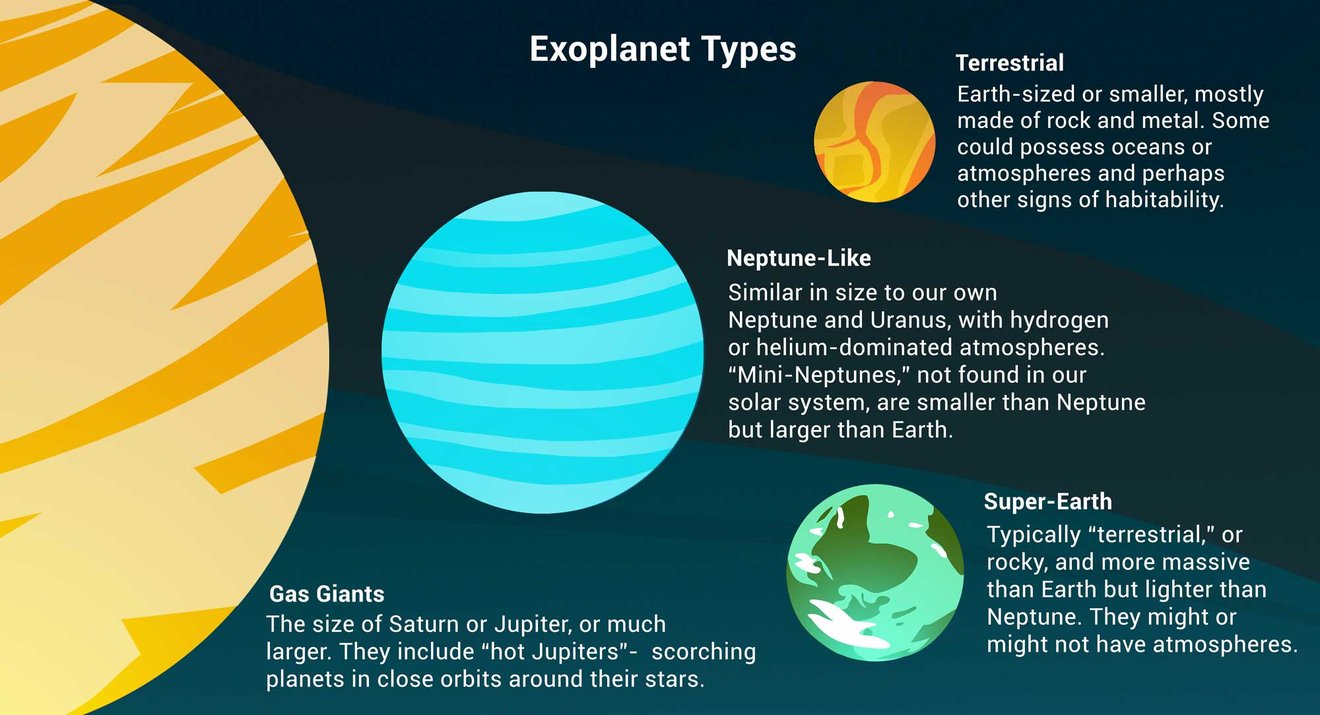

Exoplanets can be very different in size, ranging from small, rocky ones to huge gas giants. Some are in-between, like rocky super-Earths and larger sub-Neptunes with fluffy atmospheres. However, there's a noticeable gap in the sizes of planets that are 1.5 to 2 times the size of Earth (between super-Earths and sub-Neptunes), and scientists are trying to figure out why.

“Scientists have now confirmed the detection of over 5,000 exoplanets, but there are fewer planets than expected with a diameter between 1.5 and 2 times that of Earth,” said Caltech/IPAC research scientist Jessie Christiansen, science lead for the NASA Exoplanet Archive and lead author of the new study in The Astronomical Journal. “Exoplanet scientists have enough data now to say that this gap is not a fluke. There’s something going on that impedes planets from reaching and/or staying at this size.”

Scientists believe there's a gap in the sizes of certain planets because some medium-sized planets, called sub-Neptunes, might be losing their atmospheres. This loss happens when these planets don't have enough mass and gravity to keep their atmospheres in place. So, these sub-Neptunes become smaller, similar to super-Earths, creating the gap between these two sizes of planets.

The exact way these planets are losing their atmospheres has been a mystery. Researchers have considered two possibilities: core-powered mass loss and photoevaporation. The recent study provides new evidence supporting the idea that these planets are losing their atmospheres due to core-powered mass loss.

Solving The Mystery

There are two ways planets might be losing their atmospheres, causing the gap in their sizes. One way is called core-powered mass loss, where the heat from a planet's core gradually pushes the atmosphere away over a long time. It's like the core is nudging the atmosphere from below.

The other method is photoevaporation, in which the hot radiation from a planet's host star blows away its atmosphere. It's like the star's energy is acting like a hair dryer melting an ice cube.

Photoevaporation is thought to happen in the first 100 million years of a planet's life, while core-powered mass loss occurs much later, closer to 1 billion years into a planet's existence. In both cases, if a planet doesn't have enough mass, it can't hold onto its atmosphere and ends up getting smaller.

In this study, the researchers, including Christiansen, used data from NASA's K2, an extended mission of the Kepler Space Telescope. They focused on two-star clusters, Praesepe and Hyades, which are around 600 million to 800 million years old. Since planets are usually believed to be about the same age as their host stars, the sub-Neptunes in these clusters would be older than the age at which photoevaporation typically occurs but not yet old enough for core-powered mass loss.

To figure out what might be happening to these planets, the researchers looked at the number of sub-Neptunes in Praesepe and Hyades compared to older stars in different clusters. If they observed a significant number of sub-Neptunes in these clusters, it would suggest that photoevaporation hadn't occurred. In that case, core-powered mass loss would be the more likely explanation for what happens to less massive sub-Neptunes over time.

The researchers found that almost all the stars in Praesepe and Hyades still had a sub-Neptune planet or potential planet in orbit. Based on the size of these planets, the researchers believe they still have their atmospheres, supporting the idea that core-powered mass loss is the predominant mechanism for these planets rather than photoevaporation.

The study compared two sets of stars observed by NASA's K2. In the younger star clusters Praesepe and Hyades (600 million to 800 million years old), almost all stars (around 100%) still had sub-Neptune planets in orbit. This suggests that these planets likely retained their atmospheres, and photoevaporation probably did not occur. On the other hand, in older stars observed by K2 (more than 800 million years old), only 25% had orbiting sub-Neptunes. This aligns with the timeframe in which core-powered mass loss is expected to take place.

The team concluded that photoevaporation could not have happened in Praesepe and Hyades because, if it had, it would have occurred much earlier, and these planets would have little to no atmosphere left. This supports the idea that core-powered mass loss is the primary explanation for what happens to the atmospheres of these planets.

The researchers spent over five years compiling the necessary data for the study, but they acknowledge that our understanding of photoevaporation and core-powered mass loss may evolve. Future studies will likely further investigate these mechanisms before confirming the solution to the mystery of the planetary gap.

Utilizing a resource run by Caltech in Pasadena under a contract with NASA, the study made use of the NASA Exoplanet Archive. This archive is part of the Exoplanet Exploration Program, housed at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. It's important to note that JPL is a division of Caltech. The collaboration between these institutions emphasizes their roles in advancing our understanding of exoplanets and planetary systems.

More About The Mission

On October 30, 2018, the Kepler Space Telescope exhausted its fuel supply and concluded its mission after operating for nine years. During this time, Kepler made significant contributions by discovering over 2,600 confirmed planets orbiting stars beyond our solar system and identifying thousands of additional candidate planets that astronomers are still working to confirm.

The NASA Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, oversees the Kepler and K2 missions for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) was responsible for managing the development of the Kepler mission.

With assistance from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder, Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation operated the flight system. The collaboration of these institutions played a crucial role in the success and scientific achievements of the Kepler Space Telescope.

Rhyley Carney

Author

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles