Plenty of Blame Still to Go Around in Massey Mining Disaster

Leaders of the Mine Safety and Health Administration Agency haven’t done nearly enough to confront coal companies that show patterns of safety violations, critics contend.

Jul 31, 202081.2K Shares2.1M Views

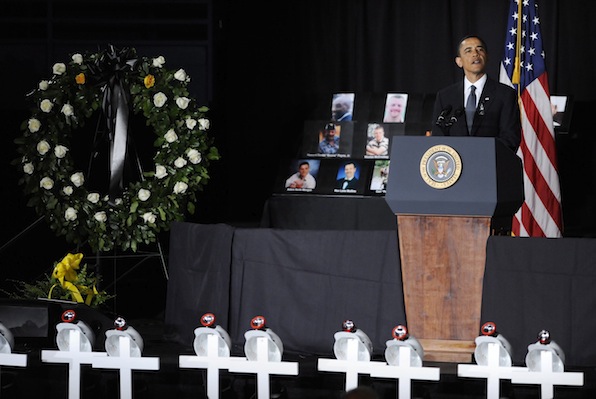

President Obama speaks at a memorial service on Sunday for miners who died in the Upper Big Branch explosion. (EPA/ZUMApress.com)

Recently released inspector notes charging Upper Big Branch operators with “negligence” on safety issues offer further evidence that the mine owner, while chiefly responsible for conditions inside the mine, wasn’t solely to blame for this month’s deadly blast, according to a number of mine safety experts. Federal regulators, they charge, also dropped the ball by failing to close the mine despite its troubled history of safety violations.

[Environment1]“This is a case not only of the operator thumbing his nose at the strictly legal requirements and regulations,” Ken Hechler, former West Virginia congressman who was lead sponsor of a 1969 law that overhauled mining safety, said this week in a phone interview. “It also involves a failure of the Mine Safety and Health Administration itself to act aggressively against the mine in order to ensure that either the conditions be made safe, as provided in the law, or to toughen the enforcement … to close the mine.”

Virginia-based Massey Energy, which owns the Upper Big Branch, “has a long history of having used every possible loophole to avoid the piling up of fines,” Hechler added, “which, of course, should have given the authority — which is clearly contained in the law — for [MSHA] to have closed that mine.”

A former MSHA manager echoed that sentiment this month, telling TWI that MSHA leaders — notably Joe Main, who heads the agency — haven’t done nearly enough to confront coal companies that show patterns of safety violations.

“[MSHA] was soft-pedaling — staying in the background, keeping a low profile,” the former official said. “And you can’t do that with this industry. You’ve got to use a big stick — especially with Massey.”

The comments arrive a few days after MSHA released inspectors notescharging operators at Upper Big Branch with “high negligence” and “a reckless disregard of care to the miners” just weeks before an explosion there killed 29 miners.

The handwritten notes, which provide further details surrounding the long-list of safety violations racked up at UBB this year, fly directly in the face of recent claims by Massey that safety is the top priority of its operations. Although these specific problems were eventually fixed, the notes could still lend clues as teams of inspectors begin investigating the cause of the blast — and Congress probes charges that Massey’s corporate culture prioritized profits above worker safety.

The inspectors notes tell a remarkable tale. One official with the Mine Safety and Health Administration visiting the Upper Big Branch on January 7, for example, found that a ventilation system — designed to flush toxic gases with fresh air pulled from outside — was pushing air in the wrong direction. “In case of an emergency,” the inspector wrote, “the men on this section would not have fresh air in primary escapeway.”

Furthermore, the mine foreman knew about the problem, the inspector noted, but when he informed higher-ups, “He was told not to worry about it.”

The vent problem, which had existed for at least three weeks prior to the inspector’s visit, “will result in fatal injuries from smoke inhalation and inhalation of harmful gases in emergency situations,” the inspector wrote, adding that such an incident is “reasonably likely to occur” in Upper Big Branch because “this mine liberates methane.”

In short, “the operator has shown a reckless disregard of care to the miners on this section and [the] men that use this escapeway,” the inspector wrote. Among those who knew of the problem, the inspector added, were Chris Blanchard and Jamie Ferguson, president and vice president, respectively, of the Performance Coal Company, a Massey subsidiary that operates the Upper Big Branch project.

That wasn’t the only instance. The same inspector, visiting another part of the Upper Big Branch on the same day, found that another vent system was pushing the toxic return air into another escapeway. The superintendent on duty knew of the problem, the inspector noted, but didn’t fix it until the inspector made a fuss.

An accident, the inspector wrote — a reasonably likely event because of the gassy nature of the mine — “will result in fatal injuries.”

“I believe [the] operator has shown high negligence [pursuant] to fact of management knowing where problem is and fixing immediately,” the inspector wrote.

There are other examples:

- On January 11, an inspector cited UBB for a misaligned belt that was rubbing another structure to the point that smoke was seen coming off the belt. A resulting accident, in that gassy mine, was deemed “highly likely,” the inspector wrote. The condition had existed for “at least two months.”

- On January 20, an inspector cited a cut in an electrical cable that wasn’t sufficiently sealed. Because the area was wet, workers were at risk of fatal electrocution, the inspector said, adding that such an episode was “reasonable likely if normal mining were to continue.” The section electrician, the inspector wrote, knew of the problem.

The notes also indicate a certain disdain among Massey managers for the MSHA officials. One company supervisor, an inspector noted on January 7, “feels as though MSHA personnel come here expecting the worst and not giving them enough benefit of the doubt. I explained to him that I would be writing what I saw.”

Appearing at a Senate mine-safety hearing Tuesday, Jeff Harris, a former Massey miner, gave a damning account of conditions in the company’s mines — testimony that was strikingly similar to accounts given by other former Massey employees.

“When we got to a section to mine coal, they’d tear down the ventilation curtain,” Harris told lawmakers. “The air was so thick you could hardly see in front of you. When an MSHA inspector came to the section, we’d hang the curtain, but as soon as the inspector left, the curtain came down again.”

Massey, for its part, has denied the claims that it doesn’t take the safety of its workers seriously — a position the company was defending as recently as this week. “Our corporate culture today stresses three priorities: safety, ethics and excellence,” reads a lettergiven to reporters Monday. “Massey Energy’s members are among the best trained, most productive and safest miners in the world.”

The company’s website reiterates that message, claiming that its “formula for success” is based on an “S-1, P-2″ model: safety first, production second. It’s a formula that some former employees are quick to dispute.

“That’s bullshit,” Chuck Nelson, a former Massey miner who’s since become an environmental activist with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, said of Massey’s safety-first claims. “You do what you’re told.”

Bolstering the critics’ claims, MSHA officials announcedTuesday that sections of three other Massey mines were shut down in recent weeks after the agency received anonymous complaints about safety concerns there. One of those withdrawals came after the Upper Big Branch explosion.

With Massey seemingly back to business as usual, Hechler said, Congress will have to play a role if policymakers hope to prevent the next mining disaster.

“Obviously, the chief burden should be on the company,” Hechler said. “But this process of writing good laws that are not enforced somehow has to be toughened to requirethe enforcement.”

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles