New Rules of Political Humor

Jul 31, 2020505 Shares504.9K Views

Image has not been found. URL: /wp-content/uploads/2008/09/obama_speaks.jpgSen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.) (WDCpix)

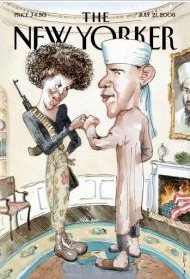

This week’s New Yorker cover, titled “The Politics of Fear,” has the distinction of being deemed “tasteless and offensive” by both the Obama and the McCain campaign. The cartoon depicts Barack Obama in the Oval Office, dressed in a turban and dishdash, and bumping his fist against that of Michele, who sports combat boots, a Soviet-made AK-47 and an afro haircut last seen on Angela Davis ca. 1970. Evidently the Obamas are celebrating Inauguration Day, and have just moved into the White House. An American flag already smolders in the fireplace, above which we see Osama bin Laden in a gilt frame. Here is Obama as a paranoid opponent might picture him in his worst nightmare.

The cartoon is obviously a parody, and its critics certainly realize this. The artist, Barry Blitt, is no great lover of Republicans and his New Yorker covers usually ridicule the Bush administration. But to judge by the outrage, Blitt seems to have crossed some invisible line that marks the acceptable limits of parody.

Just what that line is, however, is worth exploring. For it reveals something surprising about the rules of political humor, which seem different in its verbal and visual branches. It also suggests the American public’s capacity for appreciating visual humor might be changing — not necessarily for the better.

David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, defended the cover as satire: “The intent of the cover is to satirize the vicious and racist attacks and rumors and misconceptions about the Obamas that have been floating around in the blogosphere and are reflected in public opinion polls.” Unfortunately, the public, or a sizable portion of it, was unable to distinguish between “vicious and racist attack” and a parody. Blitt might have spared himself the controversy if he had placed his memorable image inside a thought bubble, and let it hover ominously over some rascally Republican head. Then it would be obvious that it is the fantasist who is the target and not the fantasy Obama. But Blitt provides no visual quotation marks to make things easy. The baffled viewer must figure out what the image is, and the slight delay before the moment of surprised realization is the cartoon’s chief pleasure.

This parody works at two levels. It not only asks us to imagine a paranoiac’s nightmare of Obama, it asks to us to imagine that The New Yorker itself was the paranoiac. In that case, the nightmare would show the genteel detachment and panache that is the magazine’s hallmark. The Obamas on the cover may be radical, but they are radical chic: they are elegant and carry themselves gracefully. It is this ironic second remove that has evidently been too much for the cover’s critics to appreciate.

Evidently, it is acceptable to say that Obama’s opponents have a warped vision of him, but unacceptable to show that warped image — even in jest. In part, this reflects hypersensitivity in the Obama campaign about any image showing their candidate in Muslim robes. They are constantly refuting rumors that the presumed Democratic nominee is a Muslim. When 2006 images of Obama dressed as a Somali elder surfaced on the Internet earlier this year, it was charged that the rival Clinton campaign was responsible.

But the discomfort seems to go deeper, and has to do with the indelible power of an image. Spoken words are less durable. People forget the punchlines of jokes, often as they are telling them, but images tend to be permanent — like the commercial jingles heard in childhood. Moreover, we look on an image as a surrogate for the person, and are acutely uncomfortable by any violation of that image, especially if it is someone we care about. For this reason, the deliberate destruction of an image — say in the hanging of an effigy — is an act with immense political ramifications, a vicarious annihilation of the person himself.

For this reason, politicians have often sought to expose the images of their opponents to public ridicule. Most bizarre, of recent examples, was the Hotel Rashid in Baghdad. Until 2003, it had a floor mosaic of the face of President George H.W. Bush. Saddam Hussein had it installed, and so forced guests to tramp on the face of the president who had bested Iraq in the Gulf War. Among the embarrassed guest who did so was Hans Blix, the U.N. weapons inspector.

The impulse to make a ceremonial image of an enemy, and then deface it, is an ancient one. According to Prof. Samuel Y. Edgerton, the author of “Pictures and Punishment: Art and Criminal Prosecution in Renaissance Florence,” such images once even performed a legal role. In Renaissance Italy, it was possible to remove a person’s reputation and good name – literally, their fama – with a legal act of defamation.

If the person was not physically present, the act of defamation was performed on a surrogate image. The town would commission a pittura infamante, a defaming picture, that showed the malefactor in the most humiliating terms. Usually, he was shown hanging upside-down by one foot, as if plunging into hell, often making an obscene gesture. Painted in fresco on the local police headquarters (in Florence, the Bargello), the person was exposed to the scorn of the town. These paintings were lucrative, and artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli are known to have competed for them. The images were taken very seriously — as we know from the frantic attempts of family members and heirs to get them removed.

In short, the controversy over Blitt’s cover is not an anomaly. In fact, it is not even the first time that a visual attack on racism has been mistaken for the thing itself, nor the first time it has involved presidential politics. In 1988, the black sculptor David Hammons painted a mural of Jesse Jackson that confronted the viewer with a spray-painted question that was also the work’s title: “How Ya Like Me Now?”

It showed a white Jackson – so pale and blond, in fact, that he might have come Stockholm – but otherwise with the same facial features. Painted during Jackson’s unsuccessful run for president, it made the argument that the only way for a black man in America to win an election was – to be a white man. When installed in Washington, it so offended viewers that a group of black man attacked it with a sledgehammer and obliterated it. Hammons, though shocked, empathized with their rage. When he rebuilt the work, he placed a set of sledgehammers in tribute to the destruction and as a kind of guard of honor.

Viewers misunderstood Hammons’s image of Jackson, just as they have now misunderstood Blitt’s image of Obama: an image meant to show the folly of an idea, by pushing it to its logical conclusion, was instead taken literally. One wonders about the American public’s ability to decode visual humor of any complexity.

It is often said that we live in a visual culture, and that visual literacy has taken the place of verbal literacy. If that is the case, the new literacy does not lend itself to ambiguity or irony.

Television watching inculcates different habits of mind than novel reading. The visual shorthand of the small screen tends to be highly literal — virtue and vice are telegraphed broadly, and the viewer tends to credit the visual truth of what is shown on the screen. The reader of a novel, by contrast, is engaged at a more active and imaginative level, and knows better than to take things literally.

Blitt asked his readers to picture the conspiracy theorist who fantasized about Obama. But for many viewers, used to being shown pictures, it is too difficult to imagine them. Whatever the ultimate ramification of The New Yorker cover, it seems safe to say that in American politics today, images can be taken only at face value.

Michael J. Lewis, an art history professor at Williams College, just received a Guggenheim Fellowship for his coming book on pietist town planning. His earlier books include “Frank Furness: Architecture and the Violent Mind” and “American Art and Architecture.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles