Obama Military Commissions Vision Takes Shape

Obama administration officials laid out in their greatest detail thus far on Tuesday for how the administration seeks to revamp the Bush administration’s use of much-criticized military commissions for foreign terrorism suspects.

Jul 31, 2020112.2K Shares2.1M Views

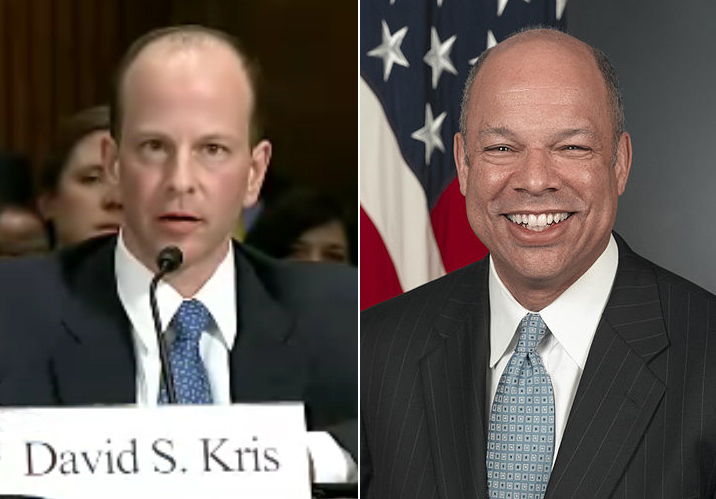

David Kris and Jeh Johnson (Senate Judiciary Committee, Department of Defense)

Obama administration officials laid out in their greatest detail thus far on Tuesday for how the administration seeks to revamp the Bush administration’s use of much-criticized military commissions for foreign terrorism suspects in order to withstand review by the courts. But the senior Justice and Defense Department officials spearheading the administration’s military commissions efforts left several aspects of their plans unclear in testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee, including the standards by which a statement from a detainee could be introduced into evidence; the criteria by which a detainee would be tried in a military commission as opposed to a federal civilian court; where the commissions could be held; and whether an acquitted detainee could be released into the continental United States.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

While reforming the military commissions is part of the Obama administration’s efforts to close the Guantanamo Bay detention facility by President Obama’s January 2010 deadline, many civil libertarian critics believe that retaining the commissions — created after 9/11 and subjected to numerous judicial-ordered modifications while only resulting in three convictions in seven-plus years — is inherently flawed. One of them, Army Reserve Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld, is a former military commissions prosecutor who resigned from the process in protest last September. “Tinkering with the machinery of the commissions will accomplish nothing,” Vandeveld said in an interview.

The Obama administration disagrees. Two senior officials, Assistant Attorney General David Kris and Pentagon General Counsel Jeh Johnson, pledged support for a Senate Armed Services Committee proposalattached to the 2010 Defense Authorization bill that restricts but does not eliminate the admissibility of hearsay evidence into the commission trials and establishes a system of appeals for commission verdicts in civilian courts for those convicted of violating the laws of war. Johnson called the panel’s commissions bill an “important initiative” to make the commissions “fair and credible.” One of the architects of the proposal, Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), the committee chairman, said he anticipated the Senate would debate the bill early next week.

Yet differences remained between the administration and the committee over the bill. Both Kris and Johnson said that they believed the commissions ought to premise the admissibility of statements from terrorism suspects captured on the battlefield on whether the statements were voluntarily provided, in order to prevent the commissions from accepting coerced testimony — a standard the committee’s legislation does not employ, although it does reject evidence obtained through torture or duress. But Vice Adm. Bruce MacDonald, the Navy’s judge advocate general, told the panel that battlefield captures are “inherently coercive,” as soldiers do not read Miranda rights to their detainees, and so predicating admissibility on voluntariness creates too restrictive a standard. “This is an area where I do disagree with the administration and I think the [Senate Armed Services] committee got it right,” MacDonald said.

But Kris said that the courts were unlikely to uphold on appeal any standard for admissibility of evidence that hinted at coercion. “There’s a serious risk that the courts will find that the voluntariness standard is required by the due process clause,” he toldSen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), the committee’s ranking Republican. Since 2004, the Supreme Court has twice ruled that the military commissions do not provide the accused with sufficient due process. MacDonald conceded that much of the deliberations over the commissions were predicated on predicting how much process protections would be necessary to provide defendants in order to placate the courts.

Vandeveld, a veteran of both the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, said the issue was a red herring. Rather than proceeding with military commissions that allow for evidence obtained through coercion, Vandeveld said that there would be evidence obtained from the battlefield that did not depend on confessions of dubious admissibility. “I was on the Joint Detention Review Committee in Iraq, which reviewed the files of security internees captured on the batlefield,” said Vandeveld, who is scheduled to testify on Wednesday morning before a House judiciary subcommittee. “Without exception, every last one of them was being held because of factual statements given by U.S. servicemembers about their apprehension. None required confessions. The idea that we’re constrained to hold someone because of their confession [being inadmissible in court] is just not true.”

Additionally, the two senior administration attorneys had difficulty distinguishing between which detainees from Guantanamo Bay would be tried in federal civilian courts and which would be tried in military commissions. Johnson said that administration reviews could easily determine that detainees capable of prosecution could be “viewed to have broken both the laws of war” and federal criminal statutes. “Where feasible, we would seek to prosecute detainees in [federal civilian] courts,” he said, adding that he and Kris were still examining the issue.

Some civil-libertarian critics of the administration interpreted Johnson’s standard to mean that the administration would seek the best venues to ensure a conviction. “‘Feasible’ means the administration will use military commissions to try individuals who would be too difficult to convict in federal court,” said David Remes, a lawyer who represents 18 Guantanamo Bay detainees. “The administration will detain without trial in either forum anyone it would be too difficult to convict in either forum.”

Johnson also deferred on the question of where the commissions would be held, saying the administration had made no decisions and “continued[d] to consider various options,” and would until the end of the year. He pledged to consult with Congress on the appropriate venue for the commissions.

Under questioning from Sen. Mel Martinez (R-Fla.) about whether Guantanamo detainees acquitted at trial could be released into the U.S. — a politically controversial issue — Johnson suggested that post-acquittal detention might still be possible. Since the administration possessed the power to detain battlefield captives under both the congressional Authorization to Use Military Force from 2001 and the general concept of the laws of war, Johnson said, those powers exist “irrespective of what happens on the prosecution side.” Asked if that rendered prosecutions moot, Johnson said that if somehow a “dangerous” person “is not convicted of a lengthy prison sentence, I think we have the authority to continue to detain someone.”

A spokesman for Johnson declined after the hearing to explain his comments. But some civil libertarians thought that Johnson’s prospective post-acquittal detentions begged the question of why the administration would bother with prosecutions in the first place. Noting that the Supreme Court affirmed in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld in 2004 that the military can legitimately detain battlefield captives until the end of hostilities, “One might well ask why try such fighters at all, as those who are at [Guantanamo Bay] are now entitled to habeas corpus to challenge the claim that they are fighters,” said Kate Martin of the Center for National Security Studies.

Added Remes, “Why try anyone when you can simply detain him? In such circumstances, a trial would merely let us tell ourselves and the rest of the world that we’re honoring the rule of law. We may be able to fool ourselves, but the rest of the world won’t buy it.”

The stated intention of both the administration’s witnesses and the Senate committee is to redraw the military commissions in order to make them “fair, legitimate, and effective,” as Kris told the panel. Kris said the administration disagreed with the committee’s allowance of classified evidence “only after an agency head or original classifying authority has certified that the evidence has been declassified to the maximum extent possible,” arguing that the review would be too burdensome on agencies where “traditional” criminal procedures for protecting classified evidence would suffice. MacDonald agreed, endorsing the criminal Classified Information Protection Act as a template for admissibility of classified information in the military commissions.

Levin said that the U.S. will still face a public-confidence problem with trusting the military commissions to administer justice even if the commissions are reformed. “However,” he said, “we will not be able to restore confidence in military commissions at all unless we first substitute new procedures and language to address the problems with the existing statute.”

Vandeveld said that any effort to reform the commissions would inevitably be struck down by the courts. The reforms envisioned by the Senate committee’s legislation and the Obama administration “will be challenged all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which will take years,” he said. “In the interim, individuals held at Guantanamo who may in fact be innocent will be held for many more years if the president doesn’t scrap the commissions entirely.”

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles