Consensus Forming on Prosecution of Guantanamo Detainees

Legal experts seem to agree that any new military commissions or national security courts, even if they provide detainees with more rights, will always be viewed as suspect.

Jul 31, 2020285.5K Shares3.8M Views

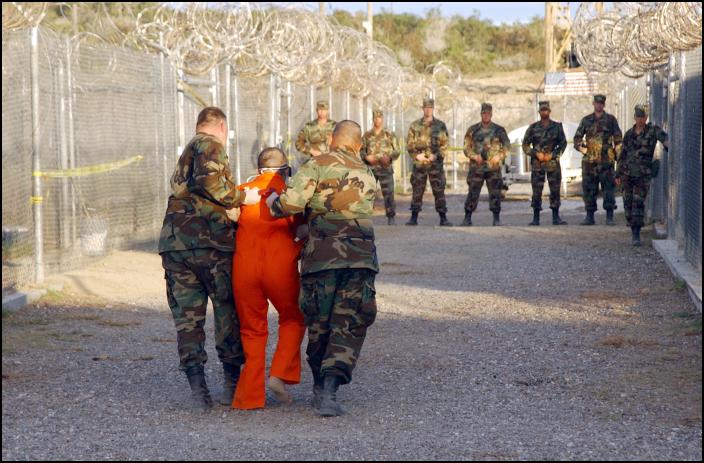

A Guantanamo detainee is escorted to his cell. (Wikimedia Commons)

On Wednesday evening during a trip to Berlin, Attorney General Eric Holder is expected to address the challenges of closing the prison at Guantanamo Bay and providing justice for the detainees still there. Whether President Barack Obama can safely return those prisoners to their home countries, resettle them elsewhere or try them in some sort of U.S. court is key to his ability to follow through on his promise to close the prison by the end of this year.

It’s also controversial. As Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said in a statement released Tuesday: “Many Americans are skeptical of the Administration’s decision to close Guantanamo before it has a plan to deal with the 240 terrorists who are currently housed there. And Americans were rightly alarmed by recent news reports that the Administration is considering releasing some Guantanamo detainees into the U.S. — not to detention facilities, but directly into our neighborhoods.”

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

McConnell was referring to Holder’s recent statementsthat he may release some of the Chinese Muslim “Uighur” detainees who’ve been cleared for release but are still at Guantanamo Bayinto the Washington, D.C. area because they can’t be returned to China for fear of persecution, and no other country will take them. Of the 240 prisoners left at Guantanamo, about 50 have told their lawyers they’re afraid they will be tortured in their home countries if returned there.

That only concerns prisoners against whom there’s little evidence of wrongdoing. Although it’s clear now that most Guantanamo prisoners are not “the worst of the worst” as former Vice President Dick Cheney often described them, at least some were involved in terrorist activities, and the challenge for the United States now is where to try them for those crimes.

In an interview with Katie Couric of CBS Newsearlier this month, Holder suggested that all options remain on the table. “We will bring, I think, a substantial number of those people who we decide to charge in Article III courts,” Holder said, referring to the civilian federal court system. “Others might be taken to military courts. Others perhaps, to these military tribunals with some – enhanced – enforcement,” he said.

Although Holder signaled that the administration is still considering the creation of some sort of new court system to try suspected terrorists, a consensus is developing among legal experts that for the vast majority of them, the civilian federal court system — where terror suspects have traditionally been tried — is still the best way to go. A broad range of experts increasingly seem to agree that any new military commissions or “national security courts”, as they’re sometimes called, even if they could be set up quickly and provided detainees more rights than did the Bush military commissions, will always be viewed as suspect and subjected to protracted challenges in federal court. And while the military justice system used to prosecute U.S. soldiers could also be used to prosecute alleged war criminals, experts say it offers few advantages over the federal court system and many practical drawbacks.

“I think it would be much better to go into a federal court system,” said Gary Solis, a retired Marine and war crimes expert who teaches international and military law at Georgetown University, and spoke at a recent legal conference on the subject. “It could be done in the military, but I don’t think it should be.”

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the Bush administration’s declaration of a “war on terror” changed the paradigm for dealing with terrorism. Instead of treating it as a law enforcement problem, which it always had been, it became a military one. That immediately changed — or discarded — the usual rules for how to treat suspects. As Judge Kenneth Karas, a federal judge in New York said earlier this month at a conference sponsored by the Center on Law and Security at New York University School of Law, “After 9-11, you didn’t have people sitting down with Miranda cards saying you have the right to remain silent. Because that’s the last thing the U.S. government wanted them to do,” he said. “So how will those cases be prosecuted?”

The problem for the Obama administration is that the suspects at Guantanamo Bay were arrested, interrogated and detained by the U.S. military and the CIA, not by the FBI, local police or federal prosecutors, who are trained to collect evidence in a way that will be admissible at trial. Evidence coerced under torture or other abuse — as described in recent Office of Legal Counsel and the Senate Armed Services Committee reports — is considered inherently unreliable and therefore inadmissible in federal court. Documents seized by the military or CIA agents, meanwhile, may not have been handled in a way that allows them to be reliably used against a defendant. And statements that soldiers or the CIA may have relied upon to capture a suspect may not be admissible in court, either, if they were based on hearsay or coerced from detainees during abusive interrogations.

That doesn’t necessarily mean we should create a new court system to get around that, argue many lawyers. “The best way to hide torture and other illegal conduct is to have a proceeding that hides some of the evidence,” said Joshua Dratel, a criminal defense lawyer who has represented detainees at Guantanamo Bay and is co-editor with Karen Greenberg of the 2005 book, “The Torture Papers: The Road to Abu Ghraib.” “The solution to a situation where there are difficulties is not to create a system that dilutes fundamental protections to the point where the court loses credibility altogether. That’s what happened at Guantanamo.”

Indeed, President Bush created the military commissions largely to get around the evidence problem. The Supreme Court struck down the first set of commissions in 2006 because they weren’t authorized by Congress and violated the Geneva Conventions. Congress passed the Military Commissions Act to solve that problem. The Supreme Court has never had an opportunity to decide if those commissions — put on hold in the early days of the Obama administration — are actually lawful. Lawyers who represented detainees tried before the commissions insisted that they were not.

Still, some prominent law professors, such as Georgetown University’s Neal Katyal, now deputy solicitor general in the Obama administration, have advocated for creation of special “national security courts”. Run by federal judges who specialize in terrorism cases, they would oversee “preventive detention” of suspects and would admit evidence that’s normally inadmissible in federal courts. Some suspects, for example, “can be tried only on a conspiracy theory that comes close to criminalizing group membership,” Katyal wrotein 2007 with Harvard Law Professor Jack Goldsmith, and “the standards of proof for evidence collected in Afghanistan might not meet every jot and tittle of American criminal law.”

But many experts say it would be a mistake for the Obama administration to create new courts now. “The Guantanamo military commissions for seven years have proven a failed and fruitless process,” Solis said. “I don’t think the international community is prepared to accept another military commission along the lines of what we had at Guantanamo Bay,” he said. “And any totally new system would be challenged just like the Military Commissions Act was.”

Kenneth Wainstein, a former federal prosecutor and homeland security adviser under President George W. Bush, acknowledged at the recent NYU conference that “as a former U.S. attorney, my bias is toward criminal prosecution, if it can be done.” He did, however, note the tension between the desire to protect classified information at trial and “the reality that in the world of counterterrorism you operate largely in a classified world.”

Many former federal prosecutors believe that world is adequately protected by current laws and procedural rules that allow judges to look at evidence behind closed doors, and allow the government to redact names of informants or to summarize critical evidence where its release in full could endanger national security. Indeed, a study of terrorism cases since 9-11conducted for Human Rights First by former federal prosecutors concluded that the federal court system is well equipped to handle such cases. The ACLU and a bipartisan coalition created by the Constitution Project, along with many lawyers who have represented detainees at Guantanamo Bay, have also argued consistently that specially created national-security courts are unnecessary and likely unconstitutional.

What’s more, as Judge Karas noted, “The perception of our allies in the fairness of how we prosecute these cases is essential for their cooperation.” U.S. prosecutors will depend on that cooperation to obtain critical evidence, so creating a new court system “has very real practical implications.”

To the extent that the current court rules don’t accommodate some of the needs of prosecuting international terrorism, those rules could be amended without creating a whole new court system, legal experts say. Some have argued that Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, for example, could be amended to make it easier to introduce deposition testimony in federal court when witnesses aren’t available.

“The questions about national security courts are complex, but the answer is simple,” Dratel said. “My answer is a categorical ‘no’. No one has yet articulated the failure of Article III Courts” to handle terrorism cases.

Although Dratel acknowledged that there could be “some tweaking in the rules,” the goal shouldn’t be to make getting convictions easy. “It’s not supposed to be easy to convict someone, to deprive them of liberty for a long time and in some cases to execute them.” The federal rules already protect classified evidence, he said, and in some cases don’t allow the defendant or even his lawyer to see that evidence. What’s more, “Confidential informants have been addressed for 40 years. It happens far more in drug cases then in terror cases. We’re not dealing with an uncharted future here,” he said, adding: “I’m skeptical of a system designed to protect evidence that will make it even more unfair.”

Of course, there’s still the military courts-martial system, whose rules are at least as stringent as those in civilian courts in terms of protecting defendants. President Obama has at times suggested that some suspects could be tried that way, since military courts have jurisdiction over war crimes. But the five-years statute of limitations on most crimes (except murder) will present a problem. “Most of these crimes, due to the length of time these folks have been held, the statute of limitations would have expired,” said Michelle McCluer, a former Judge Advocate General and executive director of the National Institute of Military Justice.

Even if the military courts could get around that problem, experts say most military lawyers, who ordinarily handle court-martials of soldiers, don’t have the sort of trial experience needed to try complex terrorism cases involving serious charges and classified evidence.

“There’s nobody in the military system who’s qualified to try these cases,” Solis said. “Not that they’re bad, just that they’re only a few years out of law school. ” Guantanamo detainees, meanwhile, “will have some of the best defense lawyers in the country,” he said, noting that some of the nation’s top lawyers rallied to defend them in habeas corpus cases and in the Bush military commissions.

If you pit skilled defense attorneys against military prosecutors with little trial experience, said Solis, who for years taught law at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, it won’t go well for the United States. “We’ll get killed.”

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles