Ties That Bind

COMMENTARY Washington again placed bets on the wrong foreign leaders. Is personal diplomacy a farce?

Jul 31, 202011.2K Shares536.3K Views

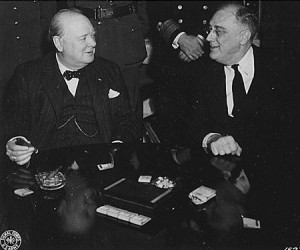

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill (Library of Congress)

One can almost hear it. “Again? We picked the wrong guy again?”

Recent events involving Pakistan, Russia and Georgia suggest that Washington has again heaped its chips on a losing number. President George W. Bush, like so many before him, succumbed to the illusion that a little personal diplomacy — oiled with a few billion in trade and aid — would secure a dependable ally in a strategic area of the world.

Then it turns out that our little buddy has flaws that should have been discernible from space. Pervez Musharraf of Pakistan was a dictator! Mikheil Saakashvili is a hothead! Vladimir Putin acts like a nuclear-armed bully who will press Russia’s interests no matter how many times Bush takes him fishing off Kennebunkport!

Can it be that personal diplomacy is a chimera – a wildly unrealistic plan for achieving basic goals? Is it possible that when we look an opponent or ally “in the eye” all we see is the reflection of our own foolish hopes?

Pundits sometimes suggest that we should just pick better. If we are going to cozy up to a Mujahadeen warlord to oust the Soviets or a Philippine senator to repress communists, we ought not to choose Osama bin Laden or Ferdinand Marcos. Bingo!

Image has not been found. URL: http://www.washingtonindependent.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/unga_ice_musharraf_pakistan-300x242.jpgSec. of State Condoleezza meets with former President Pervez Musharraf (state.gov)

Others suggest that Washington should quit trying to do anybody a favor because all you get is ingratitude. We should think in terms of interests, not good will. Leave it the Peace Corps to pass out Hallmark cards, and calculate geopolitical strategy as coldly as everybody else. In other words, accept the maxim that no nation has permanent friends, only permanent interests.

All good advice, but it ignores the historical precedents of at least four centuries.

It is the nature of diplomacy to cultivate personal relationships with foreign dignitaries no matter who they are. Ambassadors routinely serve cookies and lemonade — or caviar and vodka — to people whom they would shudder to meet under any other circumstance.

Why? Because when the proverbial excrement hits the fan, you need someone to whom you can say, “Now, Boris.”

Personal relationships are the lubricant in the machinations of government. The first job of any head of state is to protect national interests. Amicable conversation is an important venue for assessing an opponent or ally’s most cherished goals.

This is hard to do in the middle of a crisis. But on a fishing junket, or over cocktails on the veranda, national leaders hope to discover whether it is prestige, ideals, territory or money that is most likely to kindle a gleam in the eyes of an opposite number. In other words, the interlocutors cultivate insight, since this is more useful than friendship when interests collide.

And collide they will.

Perhaps the most important relationship in the history of U.S. foreign relations was that between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. One knowledgeable observer dubbed it “the friendship that saved the West.”

With all his legendary charm, Winnie initially wooed Franklin with pen and ink, sending letter after letter to the U.S. president, safe behind the Atlantic barrier. The prime minister sought the resources of the United States when Britain stood alone against Adolf Hitler. It was Churchill’s challenge to convince Roosevelt that placing his bet on the Britain would reap big rewards.

Roosevelt responded positively, even though, as he admitted to his closest aides, “I might be wrong.” One adviser, unconvinced by Churchill’s flattery, accused Roosevelt of “shooting craps with destiny.” Would this pug-faced pol prove any more resolute than Neville Chamberlain?

But even before the First Lord of the Admiralty became prime minister, FDR wrote Churchill, “I want you and the prime minister to know is that I shall at all times welcome it if you will keep me in touch personally with anything you want me to know about.”

Churchill did exactly this, assiduously cultivating the bond. When, after Pearl Harbor, the United States was finally “up to the neck and in to the death” (his words), Churchill laid down his head and “slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

But even this relationship was no bed of roses. Churchill deeply resented Roosevelt’s attempts to dismantle the British Empire. And FDR was perfectly prepared to make end runs around the prime minister if it meant achieving this objective. As much as they may have liked one another, when their goals differed, the relationship was all business.

This is not to be regretted. Politics are a bit like a market economy. The system depends on each party looking out for its own best interests — which include avoiding war, palliating local complaints, fobbing off creditors, attracting investors and making sure that neighbors stay on their side of the fence. Protecting one’s interests generally keeps people cautious and focused. Developing personal ties with all the relevant actors is a sensible move.

So where do we go wrong?

First, it is a mistake—not usually make by politicians, but common amongst the public—to think that sentimental considerations will carry anything but the lightest load. When the president says he is disappointed in his pal Vladimir Putin, it doesn’t mean that he is surprised or disillusioned. It means he hopes to sway international opinion against Russian policy. In fact, diplomats understand that while good will is important, it will never, ever trump national interest.

Second, it is naïve to wring our hands and lament that yet another relationship has gone sour when someone like Musharraf is forced to resign. He got into power all on his own. When it comes to foreign counterparts, we mostly don’t pick ‘em and we don’t control ‘em, no matter how much money we wave under their noses. They may accept our planes and tanks, but they generally do with them what they will.

A senior Bush administration official intimated last week that Washington stuck with Musharraf too long and developed few other relationships in the country to fall back on. This is the kind of mea culpa we’ve heard on innumerable occasions. Yet it’s absurd.

What if Washington had openly backed Musharraf’s opponents, and tried to bring him down? What if Bush had invited Benazir Bhutto to the White House while she still lived, or former Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif?

The reaction in Pakistan might have been akin to the American reaction when revolutionary France attempted to undermine George Washington, who was unreceptive to its demands, and then tried to sway the election of 1796 against John Adams in favor of Thomas Jefferson. All heck broke loose, and one consequence was the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts. Few things backfire as quickly as stepping over national borders to cultivate members of the domestic opposition.

The point is: you are stuck with whoever is in power. Keep your fingers crossed, cultivate “friendship” and hang on for the duration. This is called respect for national sovereignty.

Lastly, perhaps our most common mistake is to give too much money to hoped-for allies, typically for the wrong things — like buying guns.

Now, some money is reasonable. Britain’s costliest mistake in the run-up to the American Revolutionary War was to neglect alliances for which it had to pay. In those days, an alliance meant cash on the barrel-head. When the Brits decided to pinch pennies and refuse subsidies to Sweden and Russia, they had two fewer “friends” to rely on. There is no shame in spreading the wealth, especially for projects that increase social capital, like education.

Diplomacy will always be personal, but the trick is not to let it get personal – as has happened between the Russian leader Vladimir Putin and Mikheil Saakashvili. Foreign leaders are, at best, placed in power by their own people and, at worst, tolerated by them. It’s our job to paste on a smile and make the most of it.

Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman is the Dwight Stanford professor of American foreign relations at San Diego State University. She served for six years on the State Dept.’s Advisory Committee on Historical Diplomatic Documentation. She is the author of “The Rich Neighbor Policy” and “All You Need is Love: The Peace Corps and the 1960s.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles