Democrats Fed Up With Bailed-Out Banks

Democratic congressional leaders are increasingly unhappy with how the $700 billion rescue plan is being implemented. They want banks to make more loans to consumers and businesses, not continue to pay dividends to shareholders. A storm of new regulations may be coming.

Jul 31, 2020211.7K Shares3.1M Views

Bring on the finance regulations.

That’s the message this week from a growing number of Democratic leaders, who are increasingly irritated by the reluctance of the financial industry to put capital it received from the Bush administration’s $700-billion bailout to work.

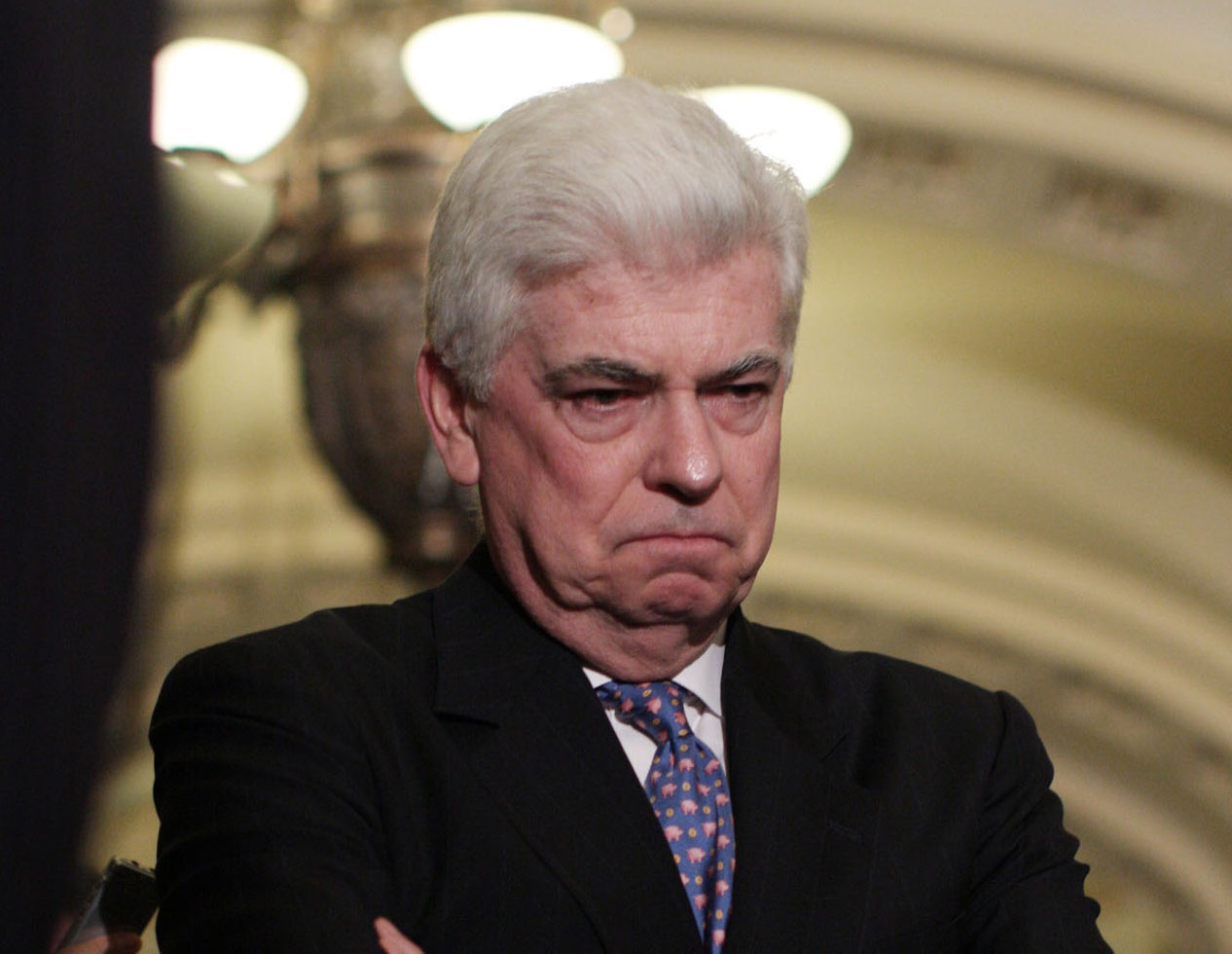

Lenders not lending. Executives keeping large pay packages. Banks distributing dividends to shareholders. The reports have been numerous. This is not, according to Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.), chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, the way the program was supposed to work.

“Let me say as clearly as I can: hoarding capital and acquiring healthy banks are not — I repeat, are not — reasons why Congress authorized $700 billion in emergency funding,” Dodd told finance industry representatives during a Thursday hearingon bailout oversight.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Dodd called on the industry to step up its efforts to stem foreclosures, accelerate lending and rein in executive pay. “And if that progress is not forthcoming,” he added, “we are prepared to legislate — now if possible, but next year if necessary.”

Like many Democrats, Dodd seemed surprised that banks and other financial institutions would be driven by profit motives. So Democratic leaders share part of the blame. After all, they caved in to administration pressures and included only minimal restrictions on how the bailout money would be spent.

The debate is at least partly ideological. The administration and many congressional Republicans oppose more industry regulations, arguing that free markets work best when governments stay out of the way. But in the middle of an economic whirlwind caused largely by poor investment decisions by banks and other financial firms, that argument has lost some steam.

“What we’ve learned over the last number of months is that consumer protection and economic growth go hand-in-hand,” the Connecticut senator said. “In fact, when you fail to do the first, you end up doing severe damage to the latter.”

Dodd’s comments come a day after Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, largely echoed Dodd. Charging that mortgage servicers have been too quick to refuse loan modifications, Frank said legislation is likely needed to encourage them.

The two Democrats’ remarks arrive as the struggling financial industry — the recipient of billions of dollars in federal help in recent months — has been slow to use the money as Congress intended.

Instead of increasing lending to thaw out frozen credit markets, for example, some banks have bought other banks. Instead of using the capital infusion to modify home mortgages and prevent foreclosures, many lenders continue to pay out dividends. In some cases, banks participating in the bailout program have given large bonuses to some employees.

Sen. Tim Johnson (D-S.D.) called for “punitive actions” if bailout funds are “misused.” Dividends and large pay packages, Johnson added, “should be rewards for a job well done — and that is currently not the case for many in this industry.”

Appearing before the Senate panel Thursday, representatives for some of the nation’s largest banks — including Bank of America, Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase — vowednot to use bailout funds for executive pay. But they defended the continuation of dividend payments, contending that those funds come from a pool of “retained earnings,” not the “capital-base” pool recently supplemented by the bailout. Also, they said, that practice will not likely change.

“We would anticipate that dividends will continue to be paid out of our earnings stream and not out of our capital base,” said Barry L. Zubrow, chief risk officer at JP Morgan Chase.

Dodd said he is “a little nervous about this distinction because … money is money.”

Under the $700-billion ressue package, passed in a din of controversy last month, the Treasury Dept. has the power to use the cash on virtually anything it deems necessary to stabilize the flailing economy.

Originally, the plan called for the Treasury to buy up toxic mortgage-backed securities and residential loans on the books of banks and other financial institutions. Treasury Sec. Henry M. Paulson Jr., however, switched gears. The government used $250 billion to recapitalize the firms in exchange for equity stakes in them. Another $40 billion went to prop up insurer American International Group.

The strategy changed again yesterday, when Paulson announced that the remainder of the bailout funds would be used to bolster consumer credit markets. But the administration must first get congressional approval, and that gives Democratic congressional leaders some leverage to alter the program, though they would have to pass new legislation to do so.

There is some indication that they will press for more transparency on how the Treasury is using the bailout money. Rep. Charlie Rangel (D-N.Y.), chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, said Thursday that the department has abused its authority in implementing the bailout. “We think they’re going beyond the discretion given to them,” Rangel said during an interview with CNN. “We are going to really legislate, if they don’t come clean with this.”

Speaking of greater transparency, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) on Thursday announced plans to reintroduce legislation to rein in another largely unregulated sector of the financial system: hedge funds. The bill would require hedge funds to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Currently, the funds are exempt from SEC oversight.

Democrats might also push the administration to do more to slow the rate of foreclosures, which triggered the financial crisis. Many experts say the larger economic crisis cannot be fixed without first stabilizing the housing market — and that means curbing foreclosures. Dodd said that it’s “still confounding” why Paulson hasn’t tackled the problem directly.

Meanwhile, the economy continues to tank. In the first week of November, the number of first-time applicants for unemployment insurance jumped to 516,000 — a seven-year high — the Labor Dept. reported Thursday.

The dismal figures may have emboldened Democratic leaders to press the administration to accept economic-stimulus legislation this month aimed at boosting consumer spending.

“Americans losing their jobs every day cannot wait for the next administration to take action,” House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) said in a statement Thursday.

Central to the plan is new spending on state infrastructure projects like bridges and roads and bailing out Detroit’s automakers — proposals the White House has resisted. In what will likely be the final squabble between the Democratic Congress and outgoing President George W. Bush, lawmakers are expected to return to Washington next week to consider the bill.

Lining up behind the administration, many congressional Republicans have fought these spending programs, as well as new regulations for the finance industry. They question the logic of attaching more restrictions on companies already down. “I think we should be very careful in moving in a direction where we’re going to mandate that mortgage companies have certain behavior,” Rep. Randy Neugebauer (R-Tex.) said this week.

Dodd, however, rejected the idea that government oversight strangles private enterprise.

“I think we need to get over that notion … that if you’re going to protect consumers, it’s going to hurt our economy,” he said. “I think we’ve learned painfully how false that statement is.”

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles