A Personal Primary

Jul 31, 202092.5K Shares1.9M Views

Image has not been found. URL: /wp-content/uploads/2008/09/obamamic.jpgSen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.) (Joe Crimmings, Flickr)

In her concession speech Saturday, Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton appealed for party unity. But did Clinton’s endorsement of Sen. Barack Obama come too late? Has the bruising primary battle so divided the party and so weakened its presumptive nominee that Obama is vulnerable to defeat despite an unpopular war and a troubled economy?

On the surface, Obama’s prospects for healing the wounds in his party look grim. In many past campaigns, bitter nomination fights like his tangle with Clinton have so undermined the eventual victors — Democrats like Hubert H. Humphrey (1968), George S. McGovern (1972) and Jimmy Carter (1980) and Republicans like Barry M. Goldwater (1964), Gerald R. Ford (1976) and George H.W. Bush (1992) — that they lost the general election.

Image has not been found. URL: http://www.washingtonindependent.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/politics-150x150.jpgIllustration by: Matt Mahurin

In many cases, these breaches not only sabotaged bids for the White House, but cost the party congressional seats. Sometimes, prominent opponents of the eventual nominee even supported the other ticket — or bolted the party entirely and launched third-party candidacies.

But Obama need not worry too much about the rifts in his own party. In every one of those cases, bruising primary battles reflected a deeper ideological split — a fundamental debate about the party’s direction and principles. Other races have witnessed contentious nomination fights — the Republicans in 1952, the Democrats in 1960. Those races, however, focused on personality rather than policy; with little ideological difference between the contenders, those battle-tested nominees triumphed in November.

The ugliest nomination fights, then, have reflected fundamental divisions, struggles for the political soul of a national party. In 1964, Sen. Barry M. Goldwater, leader of a potent grass-roots conservative movement, won the Republican nomination in a long, bitter campaign against New York Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller, the embodiment of the party’s moderate Eastern Establishment.

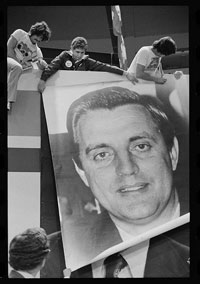

Image has not been found. URL: /wp-content/uploads/2008/09/fordcampaign.jpgRaucous Goldwater delegates practically booed Rockefeller off the stage when he tried to address the convention. “This is still a free country, ladies and gentleman,” Rockefeller shouted over the jeering crowd. While Goldwater appealed to some shared Republican principles, his acceptance speech made it clear that he valued ideological purity over party unity. “Let our Republicanism, so focused and dedicated, not be made fuzzy,” he warned the party. “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice — and let me remind you also, moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

Twelve years later, Ronald Reagan — the man who would popularize the party’s “11th commandment” against speaking ill of a fellow Republican in the 1980s — nearly deposed Ford in a primary battle that lasted until the party’s August convention. Leading the party’s emerging conservative faction, Reagan denounced Ford’s foreign policy as submission to Soviet domination and called on the party to abandon its generation-long accommodation to big government.

Thanks to an incumbent’s control of the party machinery, Ford barely held Reagan off and dumped Rockefeller, his moderate vice president for a conservative running mate, Sen. Robert Dole, in a futile attempt to paper over his party’s ideological divide. Ford lost the November elections, in part because Democrat Jimmy Carter ran strongly among white Southerners and conservative evangelical Protestants that Ford could not enlist in his coalition.

Image has not been found. URL: /wp-content/uploads/2008/09/carterdnc.jpgBut Carter himself fell victim to intramural party strife in 1980, as the incumbent president faced a tough challenge from Massachusetts Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, the champion of the party’s liberal wing. Kennedy challenged Carter’s more business-oriented approach to domestic affairs and his efforts to discipline labor unions and other liberal interest groups. Only after winning a procedural vote at the convention did the president finally clinch the nomination. Kennedy offered Carter a lukewarm endorsement — he never posed arm-in-arm in the traditional unity photograph. Many administration insiders insist that Carter never recovered.

In 1984, the Democrats divided again. Former Vice President Walter F. Mondale won the support of labor and party professionals, while Colorado Sen. Gary Hart ran a “new politics” campaign with strong appeal to affluent and young voters more interested in political reform, the environment and lifestyle issues than in the bread-and-butter concerns that drew blue-collar voters to the party. One columnist joked that Hart’s “yuppie” supporters favored the construction of a “trans-Atlantic Perrier pipeline” and the establishment of a “National Tennis Elbow Institute,” but Hart’s insurgent campaign took the struggle down to the San Francisco convention and signaled an enduring rift in the party’s ranks.

Indeed, the Hart-Mondale contest eerily echoed the Democratic primary battles of 1968 and 1972, when “new politics” candidates Eugene McCarthy and McGovern energized young Americans, brought minority voters into the process and attacked the party leadership for its corruption and, especially, its support of the Vietnam War. Hart, like Bill and Hillary Clinton, cut his political teeth as a McGovern campaign operative in 1972.

To be sure, Obama’s primary battle with Clinton has been as nasty and as difficult as any of those struggles — every one of which led to defeat in November. But bitter as it was, the 2008 race did not reflect a major political split within the Democratic Party. All the leading Democrats opposed the war in Iraq (they argued merely about who was first to that position), advocated expanded health care and called for aggressive steps against global warming. Clinton and Obama sparred over experience and judgment, electability and “elitism.” Their positions varied little; they certainly did reprise the ideological clashes of 1968 or 1980.

In fact, 2008 most closely resembled the 1960 democratic contest, when a young, charismatic senator–John F. Kennedy — wrested the nomination from a group of more seasoned politicians: Humphrey, Missouri Senator Stuart Symington, and the favorite, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas. Kennedy overcame criticisms of his inexperience and led a united party, anxious to reclaim the White House after eight years, to victory in November.

Kennedy, of course, won narrowly — he did not even capture a majority of the popular vote. Obama faces a similarly formidable test, perhaps more difficult since he cannot as easily associate his opponent with the sitting administration, as Kennedy could with Vice President Richard M. Nixon.

But should the Democratic nominee falter, he should not blame the long primary struggle for his misfortune. His party shares his essential program, and the electorate hungers for change it can believe in.

Bruce J. Schulman is the Huntington Professor of History at Boston University. His latest book, co-edited with Julian Zelizer, is “Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s.” He is the author of* “The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society and Politics” and “Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism.” *

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles