The Columbian Mosaic In Colonial America

Get to know more about the Columbian mosaic during the Colonial American period.

Author:James PierceReviewer:Paolo ReynaMay 09, 2023524 Shares104.8K Views

We might well call America a Columbian mosaic because it was the Italian admiral who effectively bound together all of the world's continents with the shipping lanes of one continuous ocean sea. When Columbus bumped into America en route to Asia after a maritime apprenticeship in Europe and Africa, he made it likely indeed, inevitable that the peoples of the world's insular continents would no longer live in splendid isolation but would soon become a single global village, due largely to European colonialism, technology, and communications. Although he never set foot on the North American continent, he was personally responsible for introducing Europeans to America and Americans albeit in chains to Europe. It was left to Nicolas de Ovando, his successor as governor of the Indies, to introduce African slaves in 1502, just as Columbus set sail on his fourth and final voyage. The paternity of triracial America is not in doubt; the only question is, how did the new American mosaic of 1790 come about?

How Did The New American Mosaic Of 1790 Come About?

One short but hardly sweet answer, which is increasingly heard as we approach 1992, is that Columbus and his European successors found a "virgin" paradise of innocence and harmony and proceeded to rape the land, kill the natives, and pillage Africa to replace the American victims of their "genocide." There is, of course, some truth to that, but not enough to be morally useful or historically truthful. If we can take our itchy fingers off the trigger of moral outrage for a spell, we might be able to view the human phase of what is being called the Columbian Encounter less as an excuse for passing judgment than as a vehicle for understanding. For in the ideological climate of the 1990s, where our collective skin is paper-thin and intolerance has been raised to an art form, we stand in sore need of some critical distance from the irreparable problems of the past. Instead of picking through the bone heaps of history for skeletons to line the closets of our current nemeses, we might better cultivate a little disinterestedness toward both the failings and successes of our predecessors in hopes of taking courage and counsels of prudence from their struggles and solutions. Since their circumstances - their field of experiences, opportunities, and limitations - is never the same as ours, we cannot draw universal laws from their example, good or ill. We can only try to emulate their good example and to avoid their worst mistakes by paying close attention to the historical circumstances in which they acted, by recognizing that their time is not our time and that we must be equally alert to the complexity and uniqueness of our own circumstances as we strive to thread a moral path through the present. Perhaps then we can recognize that the social mosaic of the 1790s, and that, although in one sense we cannot change the facts of history, we can, through a critical and disinterested examination of its causes, suggest a few ways to improve the personal and group relations we continue to fashion in the modern American mosaic.

A test of our moral mettle and patience arises as soon as we begin to discuss the influx of Europeans or "white" people into monochromatic Indian America. On the simplest level, what do we call the process and the participants? Since all language is loaded with value judgments, it makes quite a difference whether we refer to the process as colonization, imperialism, settlement, emigration, or invasion. By the same token, were the newcomers imperialists, conquistadors, invaders, trespassers, and killers, or were they, on balance, only Europeans, whites, colonists, strangers, and settlers? If modern Indians ought to have their wishes respected as to the generic names by which historians refer to their native ancestors, surely the descendants of European colonists should be accorded the same courtesy (recognizing, of course, that there may be stylistic or other reasons for not fully granting either group's wishes). It has been one of the cardinal rules of the historical canon that the parties of the past deserve equal treatment from historians - equal respect and empathy but also equal criticism and justice. As judge, jury, prosecutor, and counsel for the defence of people who can no longer testify on their own behalf, the historian cannot be any less than impartial in his or her judicial review of the past. For that reason, I suggest, we should avoid language that is inflammatory or prejudicial to any historical person or party, which is not to say that, once we have proven our case, we may not call a spade a spade, an imperialist tool, or a killer of innocent worms. If we have presented the pertinent evidence on all sides of the issue with fairness and accuracy, our audience can make up their own minds about the judiciousness of our verdicts.

How And Then?

The short answer is that Europeans emigrated in great numbers to the Americas and, when they got there, reproduced themselves with unprecedented success. But a somewhat fuller explanation must take account of regional and national variations.

The first emigrants, of course, were Spanish, not merely the infamous conquistadors, whose bloody feats greatly belied their small numbers, but Catholic priests and missionaries, paper-pushing clerks and officials who manned the far-flung bureaucracy of empire, and ordinary settlers: peasants, artisans, merchants, and not a few hidalgos, largely from the cities and towns of central and southwestern Spain. Since permission to emigrate was royally regulated, "undesirables" such as Moors, Jews, gypsies, and those condemned by the Inquisition reached the New World only in small, furtive numbers. In the sixteenth century, perhaps 240,000 Spaniards slipped into American ports. They were joined by 450,000 in the next century. The great majority was young men; only in the late sixteenth century did the proportion of women reach one-third. This meant that many men had to marry, or at least cohabit with, Indian women, which in turn gave rise to a large mestizo or mixed population. The relative unhealthiness of Latin America's subtropical islands and coasts also contributed to a slow and modest increase in the Spanish population. When the mature population finally doubled by 1628, it had taken more than fifty years, and only half the increase was due to biology; the other half was contributed by emigrants from home.

In sharp contrast to the Spanish was the French in Canada, which Voltaire dismissed as "a few acres of snow." In a century and a half, Mother France sent only 15,000 emigrants to the Laurentian colony, the majority of them against their will. Only five hundred paid their own way, many of them merchants eager to cash in on the fur and import trade. The rest were reluctant engages (indentured servants), soldiers, convicts (primarily salt smugglers), and Filles du Roi or "King's girls," sent to supply the colony's super-abundant, shorthanded, and lonely bachelors with wives. Not until 1710 were the Canadian genders balanced. But even in the seventeenth century, Canadiennes married young and produced often, doubling the population at least every thirty years. Fortunately for their Indian hosts and English neighbors, this high rate of natural increase was wasted on a minuscule base population. When Wolfe climbed to the Plains of Abraham in 1759, New France had fewer than 70,000 Frenchmen, a deficit of colonial population on the order of thirty-two to one.

Sources

The biggest source of white faces in North America was Great Britain. In the seventeenth century, she sent more than 150,000 of her sons and daughters to the mainland colonies and at least 350,000 more in the nest. In 1690, white people numbered around 194,000; a hundred years later they teemed at three million-plus. Emigration obviously accounted for some of this astounding growth. In the eighteenth century, 150,000 Scotch-Irish, 100,000 Germans (many of them "redemptioners" from the Palatinate), 50,000 British convicts, and 2,000 to 3,000 Sephardic Jews made their way to English lands of opportunity. But the proliferation of pale faces was predominantly a function of natural increase by which the colonial population doubled every twenty-five years, at that time the highest rate of increase known to demographers. After an initial period of so-called "gate mortality," when food shortages, new diseases, and climatic "seasoning" might exact a high toll, white couples in most of the English colonies began to produce an average of four children who lived to become parents themselves.

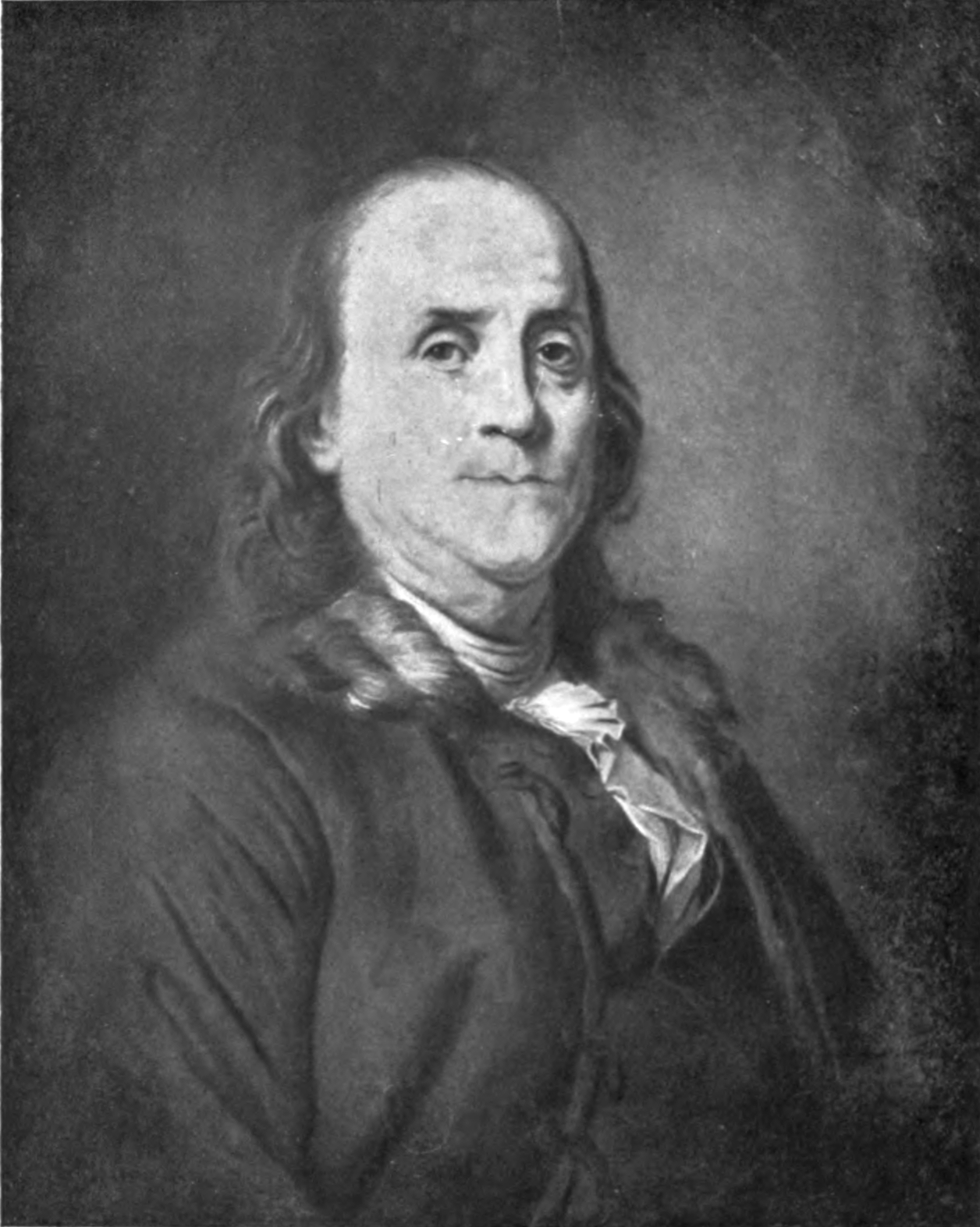

Ben Franklin

The reasons for their success were mainly two: In the words of Ben Franklin, "marriages in America are more general, and more generally early, than in Europe." Colonial women married at the age of twenty-one or twenty-two, about four or five years sooner than their European sisters, and they remarried quickly if their helpmates died, both in part because men tended to outnumber women. When their children were born (at the normal European rate), fewer died in infancy and childhood (before the ages of one and ten, respectively), and fewer mothers died in childbed. Women continued to have babies every two years, in the absence of Catholic prohibitions (as in Latin America and Canada) and birth control. But American mothers were healthier and lived longer than European mothers, thanks to sparser settlements, larger farms, more fertile land, fuller larders of nutritious food, and less virulent diseases. They, therefore, produced larger, taller, and healthier families, who in turn did the same.

The results of all this fecundity were impressive to imperial administrators, catastrophic for the Indians. The Powhatans of Virginia couldn't have been too alarmed by the initial wave of English settlers and soldiers because 80 per cent of them died of their own ineptitude and disease. But by 1640 the pale-faced population had recovered from the deadly uprising of 1622 to reach some 10,000 largely through persistent supplies from England. By 1680 the contest for the colony had been decisively won by the tobacco-planting English, who now outnumbered the natives twenty to one.

James Pierce

Author

Paolo Reyna

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles