Power Laws, Weblogs, And Inequality

A power law distribution describes how many systems and phenomena are dispersed. In a system where large is uncommon and small is prevalent, a power law holds true.

Author:Rhyley CarneyReviewer:Paula M. GrahamAug 01, 2022168 Shares2.4K Views

Clay Shirky, one of the most well-known commentators, provides a definitive explanation of how the power lawfunctions in blogs and why it is unavoidable. People who write about the social aspects of weblogging frequently mention (and typically lament) the rise of an A-list, a select group of webloggers who drive the majority of traffic to weblogs.

The pattern of this complaint is similar to what we've observed in MUDs, BBSs, and online communities like Echo and the WELL. A new social structure emerges that appears delightfully devoid of the elitism and cliquishness of the old ones. Then, as the new system expands, scalability issues arise. Not everyone can take part in every discussion. Not everyone gets a chance to speak. We all seem to be less connected than some core group, etc.

Before recent theoretical work on social networks, the typical explanations involved individual behaviors: some community members had betrayed the group, the newcomers were diluting the original spirit, etc.

These explanations are now known to be false or, at the very least irrelevant. What matters is that inequality is produced by diversity plus the freedom of choice and increases with diversity.

Even when no system members actively work toward it, a small subset of the entire population will receive excessive traffic (or attention, or income) in systems where many people are free to select from a wide range of options. No moral apathy, betrayal, or other psychological explanation can explain this. When choices are made freely and extensively enough, a power law distribution is produced.

A Predictable Imbalance

The shape of power law distributions, which gave rise to terms like the 80/20 Rule and the Winner-Take-All Society, is now well known enough to be useful. Researchers have discovered power law distributions in human systems for much of the 20th century. Vilfredo Pareto, an economist, noted that money follows a "predictable imbalance," with 20% of the population controlling 80% of the wealth.

Word frequency, according to linguist George Zipf, follows a power law pattern, with a small number of high-frequency words (I, of, the), a medium number of frequent terms (book, cat cup), and a large number of low-frequency words (peripatetic, hypognathous). Jacob Nielsen noticed power law distributions in things like website page views.

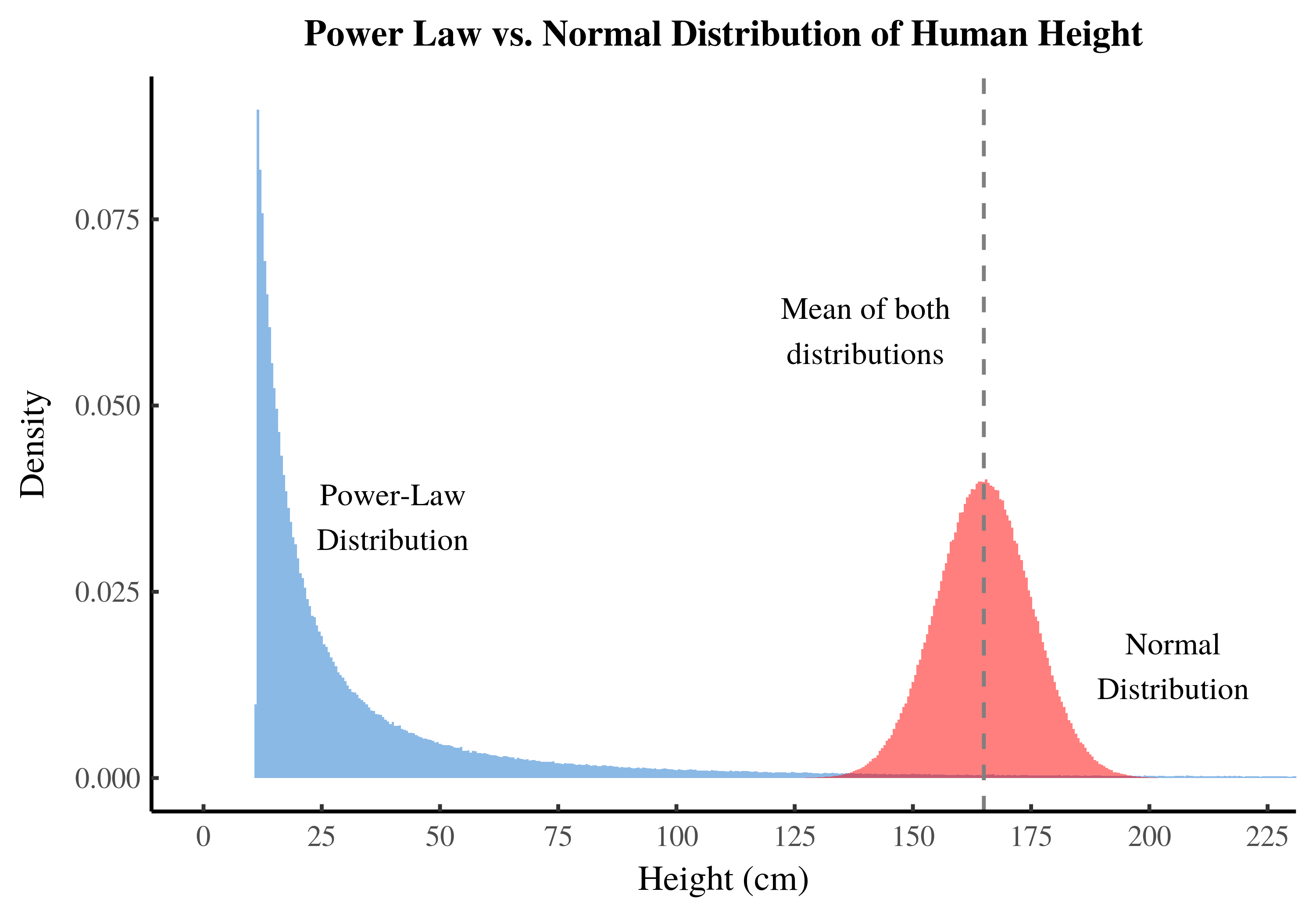

Bell curve distributions are so commonplace that power law distributions can look strange to us all. Figure #1, which displays several hundred blogs ranked by the quantity of inbound links, roughly resembles a power law distribution.

The top two websites accounted for 5 percent of the inbound links among the 433 listed blogs. Unsurprisingly, they were Andrew Sullivan and InstaPundit. Twenty percent of the inbound links came from the top dozen blogs (less than three percent of the total), and fifty percent came from the top fifty blogs (almost twelve percent).

Power law distributions are commonplace; the inbound link data is just one example. A power law distribution can be seen in the subscriber ranking of Yahoo Groups mailing lists. Figuring #2 A power law describes how friends rank LiveJournal users.

A small number of the sites will send the majority of the traffic to this content, according to the power law of traffic. If you manage a website with more than a few dozen pages, choose any time period where traffic reached at least 1000 page views, and you will observe that both the traffic from the referring sites and the page views themselves will obey power laws.

Rank Hath Its Privileges

In any system sorted by rank, the value for the Nth slot will always be 1/N. This is the basic form. The value of second place will be half that of first place, and tenth place will be one-tenth of first place, depending on what is being rated, such as money, links, or traffic.

The slope can be changed to be more or less extreme using other, more complicated formulas, but they are all related to this curve. This form has appeared in numerous systems. Until recently, we didn't have a theory to explain these observed patterns.

Now that we know that power law distributions tend to emerge in social systems where many people express their preferences among many options, thanks to a series of breakthroughs in network theory by researchers including Albert-Laszlo Barabasi, Duncan Watts, and Bernardo Huberman, among others, breakthroughs being described in books like Linked, Six Degrees, and The Laws of the Web.

Additionally, we know that the curve grows more dramatically as the number of alternatives increases. Contrary to what most of us would think, increasing the number of options does not flatten the curve; rather, it widens the gap between the top choice and the median choice.

A second counterintuitive feature of power laws is that most components in a power law are below average due to the curve's extreme favoring of the best performers. When cumulative links are divided by the total number of blogs, as shown in Figure #1, the average number of inbound links is 31.

Two-thirds of the listed blogs have below-average inbound links because the first blog with fewer than 31 links is 142nd on the list. It seems difficult to think that two-thirds of a population would be below average because we are accustomed to the bell curve's evenness, where the median position represents the average value. (The actual median has only 15 inbound links and is ranked 217th out of 433)

Freedom Of Choice Makes Stars Inevitable

Think of a hypothetical population of 1,000 people who each choose their ten favorite blogs to illustrate how freedom of choice could result in such unequal distributions. Simply assuming that each user has an equal likelihood of loving each blog is one way to construct such a system.

This distribution would essentially be flat because the same number of people will typically mark a blog as a favorite. Of course, some blogs will be more popular than others and vice versa, but this is statistical noise. The majority of the blogs will have an average readership, and their highs and lows won't deviate significantly from this average.

The writing's quality or other people's preferences have no bearing on this paradigm; there are no shared preferences, no favorite genres, no marketing effects, and no referrals from friends.

However, decisions made by one person may impact another. The system drastically changes if we believe that each blog picked by one user is more likely, even slightly, to be chosen by another user.

The first user, Alice, makes her blog selections independently of the other users, but Bob is slightly more likely than the other users to find Alice's blogs appealing. After Bob is finished, any blog that Alice and Bob both like has a larger likelihood of being chosen by Carmen, and so on, with a select few blogs growing more likely to be chosen in the future as a result of being selected in the past.

Consider the compliments as a preference premium. The approach implies that later users enter an environment that has already been formed by earlier users; the 1,000th user won't be choosing blogs at random but rather will be influenced, even if unintentionally, by the preference premiums that have already been built up in the system.

Keep in mind that this model says nothing about why one blog might be favored over another. Some writing may be superior to the norm (a preference for quality), some people may seek out recommendations from others (a preference for marketing), and some people may find it advantageous to read the same blogs as their friends (a preference for "solidarity goods," things best enjoyed by a group).

For different readers and writers, it might be one or more of the three or altogether different. What important is that any trend toward agreement, however minor and for whatever cause, can lead to power law distributions in varied and free systems.

Because it occurs naturally, altering this distribution would necessitate both worldwide control and the use of force, as it would involve compelling hundreds of thousands of bloggers to link to some blogs and remove links from others. The village would need to be destroyed in order to reverse the star system and save it.

Power Law Distribution And Its Examples And Application- Statistics Interview Question

Inequality And Fairness

Asking if there is inequality in the weblog world (or practically any social structure) is the wrong question because the answer will always be yes, given the prevalence of power law distributions. Is the inequality fair is the crucial query. The current imbalance may be essentially fair, according to four factors.

The first is, of course, the freedom that exists in the weblog community at large. The threshold for starting a weblog is only infinitesimally higher than the criterion for being online in the first place because there is no expense and no approval process.

Second, blogging is a regular activity. Even if Josh Marshall (TalkingPointsMemo.com) and Mark Pilgrim (DiveIntoMark.org) are well-liked, if they stopped or even considerably reduced their writing, they would vanish. Blogs are not the best place to savor your successes.

Third, the stars exist because hundreds of other people have chosen to point to them, not because of some cliquish preference for one another. It would be difficult to create the kind of dispersed approval that has made them famous.

Finally, since there is no discontinuity, there is no true A-list. Although descriptions of power laws, like the one presented here, sometimes focus on statistics like "12% of blogs account for 50% of the connections," these are artificial benchmarks. By definition, the #1 and #2 places in a power law contain the most significant step function. Any distinction between blogs with higher and lower traffic is arbitrary because there is no A-list that is qualitatively distinct from their closest neighbors.

The Median Cannot Hold

Although the disparity is currently fairly fair, the system is still in its infancy. Once a power law distribution has been established, it may exhibit some degree of homeostasis, or a system's propensity to maintain its shape despite external pressure. Is there such a system in the blogosphere? Exist persons who are equally talented or deserving as the stars of today, but who do not receive anything close to the attention? Doubtless. Will this issue deteriorate worse in the future? Yes.

Although there are more new bloggers and readers every day, the majority of the new readers are increasing the traffic of the top few blogs, while the majority of new sites receive below-average traffic.

As the weblog world develops, this traffic disparity will widen. It's not impossible to start a successful new blog and gain a large readership, but it's more difficult now than it was last year, and it will be even harder the following year. Weblog technology will eventually be used as a platform for so many different types of publishing, filtering, aggregation, and syndication that the term "blogging" will no longer be used to describe any especially coherent activity (possibly one we've already past).

The term "blog" will fade into obscurity, much like "home page" and "portal," words that formerly had specific meanings but have now lost them due to overuse. This will occur when the head and tail of the power law distribution diverge to the point that it is impossible to imagine Glenn Reynolds of Instapundit and J. Random Blogger acting in concert.

Webloggers who join mainstream media—a term that seems to mean "media we've gotten used to"—will be at the forefront. The change is straightforward: when a blogger's audience expands, more people read her work than she can potentially read; she is unable to link to everyone who requests her attention; she is also unable to respond to all of her emails or comments left on her blog. Due to these constraints, she eventually becomes a broadcast source, disseminating information without participating in discussions about it.

The long tail of blogs with few followers will transition to conversational in the interim. The sole criteria for success in a world where the majority of bloggers receive below-average traffic cannot be audience size. By anticipating that users would be writing for their friends rather than some impersonal audience, LiveJournal had this figured out years ago.

An essay published and read by three random people is a recipe for disappointment, but a Saturday night narrative read by your three closest friends feels more like a dialogue, especially if they respond with their tales.

Due to its superior friend and group relationship tracking, LiveJournal has an advantage over most other blogging systems. However, as generic blog technologies like Trackback become more prevalent, more blogs may be able to adopt this conversational mode.

Blogging Classic, which consists of blogs written by one or a small number of people for a moderately-sized audience and with whom the authors have a relatively complicated relationship, will fall between blogs as mainstream media and blogs as dinner conversation.

Due to the weblog industry's continued expansion, more blogs will follow this pattern in the future. However, both in terms of traffic (which is overwhelmed by blogs from the mainstream media) and an overall number of blogs, these blogs will be in the minority (outnumbered by the conversational blogs.)

People Also Ask

What Is Power Law Used For?

The power law describes a phenomenon where a few items are concentrated at the top (or bottom) of distribution and consume 95% of the resources. In other words, it implies that smaller numbers of occurrences are typical and higher numbers are uncommon.

What Are The Power Laws In Math?

The Power Rule for Exponents: (am)n = am*n. To raise a number with an exponent to a power, multiply the exponent times the power. Negative Exponent Rule: x–n = 1/xn.

What Is The Power Law In Nature?

A power law is a unique type of mathematical relationship where one quantity changes as a power of the other. Power laws are everywhere in nature. For instance, a word's frequency in a language is inversely related to its position in a frequency table.

Conclusion

For the same reasons stop-and-go traffic happens on congested roads, inequality exists in vast and unrestrained social systems because it is a predictable attribute that emerges from the regular operation of the system rather than because it is someone's intended outcome.

The early years' largely equal readership distribution had nothing to do with the nature of weblogs or webloggers. There simply weren't enough blogs to have distributions that were that uneven. There are now.

Rhyley Carney

Author

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles