A Flood of Money Slow to Fix New Orleans Schools

“The capacity to find a facility is not tied to school performance,” says one New Orleans school principal. “I understand that, but I really wish there was a clearer path.”

Jul 31, 202017.9K Shares897.9K Views

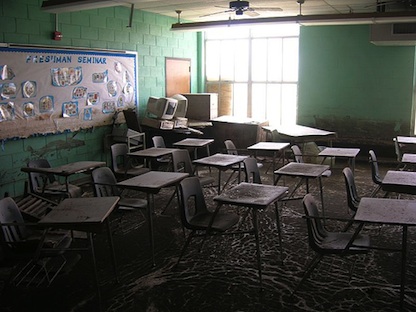

A school damaged by Hurricane Katrina. (Flickr, Paul Baker)

*This week, *The Washington Independent is featuring a series of investigative stories on the rebuilding of New Orleans, five years after Hurricane Katrina. Find all of them here.

After Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, the federal government began the most expensive long-term rebuilding project in American history. The Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other organizations sent billions of dollars — the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center puts the total at $45 billion — to the Gulf Coast for the repair and reconstruction of housing, primarily, but also for the rebuilding of infrastructure like roads, sewers, libraries and prisons. In Louisiana, however, by far the biggest chunk of infrastructure funding is going to schools. But that does not necessarily mean that schools have come back online quickly enough. Indeed, despite the government’s best efforts to funnel a lot of cash fast to education, the pace of recovery remains slow.

[Environment1] Over the past five years, the recipient of the largest slice of rebuilding money in the state has been the Recovery School District, which took over most of New Orleans’ public schools after the storm. Since Katrina, the RSD has been allocated more than $763 million, according to a TWI analysis of data from the Louisiana Recovery Authority. In his speech Sunday, President Obama touted a settlement between FEMA and New Orleans’ schools that would send another substantial injection of funding into the system. “Just this Friday, my administration announced a final agreement on $1.8 billion dollars for Orleans Parish schools — money that had been locked up for years — so folks here could determine how best to restore the school system,” he said.

Even before this agreement, K-12 public schools as a group were slated to receive more than $1.7 billion — more than three times as much as the next largest group of recipients, hospitals and health care providers. Add to that sum this new infusion, which represents more than $900 million in additional funding, along with money received by K-12 private schools ($521 million), public higher education ($195 million), and private higher education ($144 million), and the total rebuilding money for Louisiana schools comes to more than $3.4 billion.

Since taking office, the Obama administration has promised to “cut the red tape and bureaucracy” for the recipients of disaster recovery money, as the President said Sunday, and the agreement with New Orleans’ schools helps the administration argue it is keeping that promise. The process that the Recovery School District had to navigate to get to this point, however, goes a long way towards explaining why, five year after Katrina, the city is still just beginning the process of rebuilding.

As recently as December, Janet Napolitano, the secretary of Homeland Security, looked outside the Recovery School District for an example of how FEMA funding was reviving New Orleans. She held up Holy Cross, a private Catholic academy, as evidence that the administration was helping to “cut through red tape and streamline and expedite the decision-making process for public assistance” in the Gulf Coast. (The red tape trope is a refrain for the Obama administration: Secretary Napolitano used similar language when describing the RSD settlement on Friday.) Holy Cross’ old campus was located in the Lower Ninth Ward. After Katrina, the school’s leaders decided to move it to Gentilly, a neighborhood left less damaged by Katrina. In the fall of 2009, the school welcomed students to its new campus; by this winter, phase one of the school’s reconstruction, complete with a new gym and performing arts spaces, should be complete.

Holy Cross raised money from private investors to help finance its rebirth, but it is also down for $82 million of FEMA funding, more than $70 million of which the school has already received, according to the Louisiana Recovery Authority’s data. The school ranks 20th on the list of the Louisiana funding applicants who have had the most money obligated to them, according to TWI’s analysis.

Holy Cross had to overcome its share of bureaucratic hurdles, but with the help of a local consultant with experience in public assistance grants and with the support of officials from the local to the federal level and of the surrounding community, the school was able to navigate the process, says Stanton Vignes, who served on the executive committee of the school’s board for the past six years. “The process is tremendously bureaucratic and ever-changing, but we always realized it was a process,” he says. “We had a direction; we knew what we were doing; we knew where we wanted to be. That’s why we were so far ahead of the curve.”

The Recovery School District is not lagging so far behind; it opened the Langston Hughes Elementary School in August 2009, around the same time Holy Cross occupied its new campus. But ultimately, between rebuilding and repairing, the district needs to bring 87 school campuses up to snuff. (The final total depends on how the city’s population rebounds.) Langston Hughes was one of five Quick Start schools chosen for fast-tracked construction. Students occupied three additional schools in January 2010, and the fifth, L.B. Landry High School, opened in early August.

Across the city, however, more than 7,000 public school students, almost one out of every five, are still learning in “modular classrooms” — essentially, trailers. The New Orleans Charter Science and Math Academy, known as SciAcademy, has been in modular classrooms since 2008, its first year of operation, for instance. SciAcademy is one of the success stories of the post-Katrina education system: In its first two years, it has taken struggling high school students, some of whom were reading at a third-grade level, and brought them up to age-appropriate levels of achievement. This month, the school’s staff was preparing for the students’ arrival, rehearsing their plan for the first day and practicing responses to dicey situations, when the news came that they would have to pack up the entire school and move to a new, but still temporary, site.

“The capacity to find a facility is not tied to school performance,” says Ben Marcovitz, the school’s principal. “I understand that, but I really wish there was a clearer path.”

Part of the problem is that, initially, to receive funds from FEMA, the Recovery School District had to work on each project independently, which slowed down the entire process. Each building had its own project worksheet, used to assess damages and determine compensation. “Very early on, you may have had the same problem on every project, but FEMA treated every project differently,” says Lona Hankins, the district’s director of capital projects. “They’d rule differently. We’ve had to learn to fight those battles on a system-wide level.”

Without the lump settlement, it was more difficult for the district to plan the wholesale reconstruction of the school system. Earlier this month, for instance, the Recovery School District released a draft plan of long-term building assignments for all schools currently operating in the district. The reconstruction plan is divided into phases, however, and school leaders slated for buildings in later phases wondered if the district would be able to fund its ambitious plan.

Now, however, that worry is moot. The district estimated the cost of its master plan at $1.6 billion; the $1.8 billion FEMA settlement should be sufficient to rebuild or repair the rest of the district’s schools, if the process continues according to plan. The district has hired a pool of architects to take on the remaining projects as they reach the head of the line. Now all that remains to do is build the schools. The 24 new or totally renovated schools in phase one of the reconstruction plan should all be open by the fall of 2013. After that, the district will have only five more phases of construction to complete before New Orleans’ schools are finally rebuilt.

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles