Frank Balances Interests on Finance Reform

Even with public anger at banks reaching new levels, Rep. Barney Frank can’t ignore the powerful finance industry.

Jul 31, 2020110K Shares2.5M Views

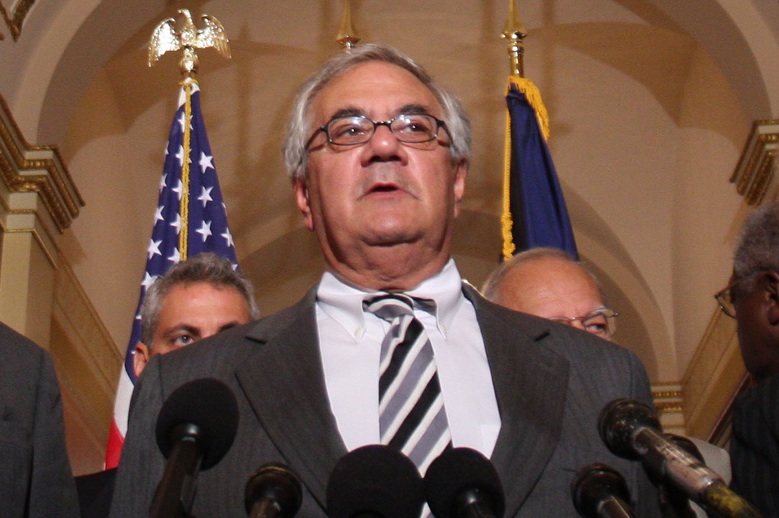

Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.) (WDCpix)

Pointing to unregulated lending as the root of the economic meltdown, the head of the House Financial Services Committee on Tuesday delivered two distinct messages before a gathering of bankers: One, you are not to blame for the crisis and, two, prepare to be regulated.

If only the regulated banks were making mortgage loans then “we wouldn’t be in the crisis we are today,” Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.) told members of the American Bankers Association, carving the oft-forgotten distinction between banks, like Wells Fargo and Wachovia, which are monitored by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and non-bank lenders, like Bear Stearns and AIG, which are not. “The bad loans were made by the people who were unregulated.”

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

The hundreds of ABA members burst into applause.

Yet Frank is also pushing a series of reforms targeting banks and non-banks alike — and opposed by both. Already this month, legislation empowering bankruptcy judges to alter primary mortgages has passed the House, and other proposals to rein in predatory lending practicesand reform the credit card industrywill likely move shortly after lawmakers return from the Easter recess. The ABA opposes all three.

In may ways, Frank is walking a tightrope between promoting the reforms he wants passed and trying not to alienate the industry those policies target. One minute he’s singing the virtues of free enterprise, telling the bankers that, “the private sector is what creates the wealth,” and, “you ain’t Sweden.” The next moment he’s warning the same crowd of new executive compensation restrictions for the largest bailed out banks, citing “a very angry public” in the wake of the AIG-bonus outcry. The success of finance reform legislation this year will hinge on the ability of Frank and other Democratic leaders, particularly in the Senate, to strike a balance between these conflicting interests.

The consequences of alienating the industry have already been made evident this year. The House-passed “cramdown” bill has stalled in the Senate while industry defenders attempt to water it down. The message is clear: The finance industry might be flailing, and it might be reliant on government bailouts, but it’s retained much of its historic sway over Congress.

That dynamic has turned Frank into one-part legislator and one-part lobbyist for the Democratic agenda. Attempting to convince the bankers of the merits of his anti-predatory lending proposal, for example, Frank said Tuesday that the bill — which prohibits lenders from making loans before securing evidence that the borrowers can repay — is based on “the banking model.”

The hundreds of bankers sat silent.

That silence should come as no surprise. When a similar anti-predatory proposal passed the Housein November of 2007, the ABA criticizedthe legislation for the “increased regulatory burden for federally insured depository institutions, lack of a national standard and the impact on a bank’s ability to provide products and services — all of which would increase costs and decrease choices for consumers.”

Reacting Tuesday to the Democrats’ plans for credit card reforms, which the Senate Banking Committee passed the same day, the ABA issued a statement warningthat “lenders of all sizes will likely have to pull back on providing reasonably-priced credit to a wide range of consumers and small businesses. It is hard to see how that makes good policy sense.”

Perhaps with such critiques in mind, Frank was careful to focus much of his attention Tuesday on those who weren’tin the room: the non-bank firms like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch, which bought and sold mortgage-backed securities without maintaining the capital reserves to prevent collapse when the housing market tanked.

Much of the confusion and public anger over the bailout, Frank said, stems from the popular misconception that there’s nothing distinguishing the regulated banks from the largely unregulated non-banks. “The public doesn’t always differentiate as well as they should,” he said.

Frank reiterated his support for empowering a new regulator to oversee such non-banks, much the way the FDIC currently monitors commercial banks, like those represented by the ABA. That regulator, he said, would prevent the non-banks from overleveraging their debts — a condition under which banks and insurance companies already operate.

“They issued credit default swaps under the assumption that property would go up and up and up,” Frank said of the non-bank lenders. The process was like selling life-insurance to vampires with the expectation that they’d live forever, he said. “And then the vampires started to die.”

Frank spokesman Steven Adamske said Tuesday that consideration of the anti-predatory lending bill, sponsored by Rep. Brad Miller (D-N.C.), was previously expected in the Financial Services panel this week, but has been pushed until after the Easter recess, which ends April 20.

That gives Frank and the Democrats plenty of time to rally support. It also lends the finance industry more opportunity to secure opposition.

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles