Senate GOPers Press for Prosecution of Bush Officials

The judiciary committee hearing seemed a little backward -- with Democratic Sen. Patrick Leahy calling for a truth commission and Republican Sen. Arlen Specter pushing for a full-fledged prosecution.

Jul 31, 202024.3K Shares1M Views

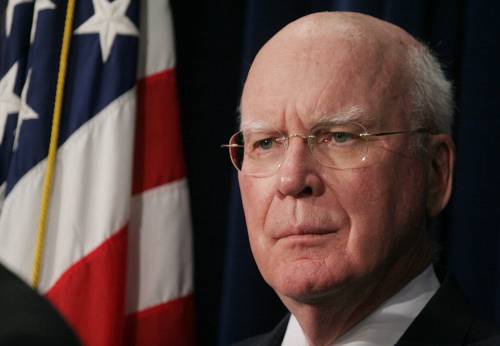

Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) (WDCpix)

Watching the Democratic chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee push for a “truth commission” while his Republican counterpart appeared to press for prosecution of Bush administration officials seemed an odd turn of events. But then, the entire Senate Judiciary Committee hearing Tuesday, “Getting to the Truth Through a Nonpartisan Commission of Inquiry,” seemed a little backwards.

“Nothing has done more to damage America’s place in the world than the revelation that this nation stretched the law and the bounds of executive power to authorize torture and cruel treatment,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) in his opening statement. “The Bush administration chose this course, but tried to keep its policies and actions secret, knowing that they could not withstand scrutiny in the light of day. How many times did President Bush go before the world and say that we did not torture and that we acted in accordance with law?”

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Leahy’s statements would seem to be supporting the prosecution of Bush administration lawbreakers. But instead, Leahy yesterday re-iterated his call for “a middle ground to get to the truth of what went on during the last several years, in a way that invites cooperation. . . I believe that that might best be accomplished though a nonpartisan commission of inquiry. I would like to see this done in a manner removed from partisan politics.”

Judging from the reactions of the Republicans on the committee – or, at least from Sens. Arlen Specter (R-Penn.) and John Cornyn (R-Tex.), the only two Republicans who attended –– there’s not going to be much cooperation from the other side of the aisle.

Specter, the judiciary committee’s ranking Republican, decried the “commission of inquiry” as a “fishing expedition.”

“If there’s reason to believe that these Justice Department officials have given approval for things that they know not to be lawful and sound, go after them,” he said, referring to recent memos released from the Office of Legal Counsel that authorized extreme and arguably illegal executive powers. “Some of the opinions that are now disclosed are more than startling — they’re shocking.”

The revelations, said Specter, who’s a former federal prosecutor, are “starting to tread on what may disclose criminal conduct,” he said.

The witnesses called to support the Republican position seemed to agree.

David Rivkin, a former Justice Department official in the Reagan and first Bush administrations, called a truth commission “a profoundly bad idea, a dangerous idea, both for policy and for me as a lawyer for legal and constitutional reasons.”

Such a commission “is to establish a body to engage in what, in essence, is a criminal investigation of former Bush administration officials,” he said. Matters such as the interrogation and treatment of terror suspects and domestic warrantless wiretapping, however, are “are heavily regulated by comprehensive criminal statutes.” Any such investigation, then, “ensures that the commission’s activities would inevitably invade areas traditionally the responsibility of the Department of Justice.”

Rivkin went on to strengthen the case for a criminal prosecutions by arguing that if a commission were to unearth evidence of criminal activity and not prosecute it, it would leave former Bush administration officials open to prosecution abroad.

“One of the commission’s most dangerous effects would be to increase the likelihood of former senior U.S. government officials being prosecuted overseas, whether in the courts of foreign countries or before international tribunals,” he said. Noting that Bush administration officials have been accused of violating “not only U.S. criminal statutes but also international law, and which are arguably subject to claims of ‘universal jurisdiction’ by foreign states,” foreign prosecutors could use the facts set forth by the commission – “especially if it is the only ‘authoritative’ statement on the subject by an official U.S. body – as a ready pretext for their bringing charges against individual former U.S. officials.”

Such prosecutions could not go forward under international law if the United States were to conduct prosecutions in its own criminal justice system.

Jeremy Rabkin, a law professor at George Mason University who serves on the board of the United States Institute for Peace, similarly testified at the hearing yesterday that a truth commission is an inappropriate substitute for criminal prosecution.

In South Africa and Chile, and “in many other countries in Latin America, in Africa, in Eastern Europe, truth commissions were established as an alternative to prosecutions because prosecutions would have endangered precarious transitions to democratic, or civilian, government,” he said.

“We are not remotely in that situation in the United States. If actual crimes were committed by officials of the Bush administration, there is no reason at all why they should not be prosecuted in the ordinary way we prosecute crimes.”

Oddly, it was the Democrats at the hearing who were arguing for a softer but broader fact-finding approach. Among the witnesses supporting a truth commission — although not necessarily in lieu of prosecutions — were Ambassador Thomas Pickering, Retired Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, former 9/11 commission senior counsel John Farmer and Frederick Schwartz, who was chief counsel to the Church Committee that investigated intelligence abuses in the 1970s. All spoke eloquently in favor of the need to expose the full truth about the abuses committed as part of U.S. counter-terrorism policy after September 11.

Schwartz, now chief counsel at New York University Law School’s Brennan Center for Justice, said that how the United States has handled counter-terrorism is “too important to sweep under the rug. Those who don’t understand errors of the past are condemned to repeat them and surely will.” Schwartz characterized a truth commission as a “first step” to knowing all the facts – “how were decisions made, who was consulted and who was not consulted. What were the consequences of our actions. And what are the root causes of having gone down a path that was inconsistent with our values and seems to have broken the law.”

Democratic Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (R.I.) and Russ Feingold (Wis.) also spoke in support of a truth commission. But the fact that only three senators on the Judiciary Committee asked questions, and only five showed up – and some didn’t even stay for the entire hearing – does not suggest overwhelming support for the idea.

In fact, a truth commission remains a controversial propositionacross the political spectrum. Leahy has repeatedly said that a commission would not be designed to further potential prosecutions, but Republicans attack it as an unlawful stealth prosecution, while many civil and human rights advocates insist that prosecutions of any senior officials who developed illegal policies and authorized illegal activities are necessary.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and the National Religious Campaign Against Torture, to name a few, have all called for independent prosecutors to investigate criminal activity, although they all also support a broader inquiry.

The ACLU is advocating for a Select Committee that, like the Church Committee of the 1970s, would have broad jurisdiction but would be an exercise of the Congressional oversight role.

“It can tell the comsplete story,” said Chris Anders, legislative counsel for the ACLU after yesterday’s hearing. “It’s not limited to particular departments or agencies. It could be set up to cut across the government, including the White House. It’s also Congress itself exercising its obligations to the system of checks and balances and not delegating it off to anybody else. For the long term health of the democracy it’s good to get Congress in the practice of exercising its oversight muscles.” While a select committee i a good way to do that, he said, “we’ll take the truth where we can get it.”

Advocates of the Leahy-style “commission of inquiry”, meanwhile, stress the benefit of an independent commission of nonpartisan investigators who can investigate the role of the entire government and couldn’t be accused of diverting Congress from more immediately pressing issues, such as the economic crisis.

“The role of Congress really ought to be looked at too,” said Lisa Magarrell, senior associate at the International Center for Transitional Justice, who attended yesterday’s hearing. “Questions ought to be asked about whether members of Congress knew things and should have done things based on that knowledge. It’s not impossible for a select committee to ask that, but it’s more difficult.”

Even if Leahy can’t win congressional support for a truth commission, yesterday’s hearing succeeded in calling even more attention to the growing body of evidence of illegal counter-terrorism activity by the Bush administration. Earlier this week, the Department of Justice released nine memosfrom the Office of Legal Counsel that revealed that Bush lawyers pronounced that the Bill of Rights did not applyto the Defense Department acting on U.S. soil, and that the First Amendment could be suspended by the President in wartime. Many of these memos may have been used to justify illegal conduct by Bush administration officials. According to a New York Times report, the Justice Department is planning to release more such memos soon. The ACLU, CCR and others have pending FOIA lawsuits that seek memos specifically pertaining to the interrogation and treatment of detainees.

Also last week, the CIA admitted it destroyed 92 videotapes of harsh interrogations that the ACLU had been seeking in a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. Those tapes were destroyed in 2005, well after revelations of torture, rape and murder of prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

Last week the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence announced it would convene an investigation into the CIA’s interrogation tactics since the September 11 attacks.

Even if Republicans don’t support a broader truth commission, it’s notable that in opposing it, they appear to be making a strong case for criminal prosecution.

“They may be taking a calculated risk that there won’t actually be support for prosecutions, but one has to take at face value that those were genuine statements by people who were opposed to a commission,” said Magarrell, after the Judiciary Committee hearing on Wednesday. “I think the question is whether the justice department starts to look more proactively at a prosecution. Certainly there are reasons to be investigating things deeper. Pretty much everyone today seemed to indicate that that was appropriate.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles