Truth Commission Talk Sparks Conflict

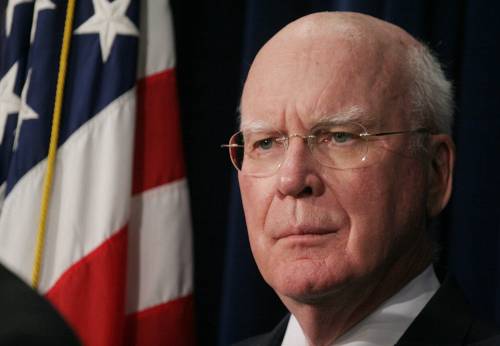

Sen. Patrick Leahy’s comments on the possibility of an investigation into Bush torture policies offered legitimacy to a debate over how to handle the past.

Jul 31, 2020140.9K Shares2.8M Views

Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) (WDCpix)

When Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) last week told an audienceat Georgetown University that Congress should convene a “Truth Commission” to investigate allegations of Bush administration wrongdoing, his remarks set off a firestorm. Within minutes, Leahy’s statements were zipping across the blogosphere, and by evening made the headlines on cable news. Although discussed for years among legal experts and already the subject of a House bill proposed in January, the idea of investigating Bush officials for crimes connected with the “war on terror” had been largely dismissed, even among Democrats, as politically implausible. The Senate Judiciary Committee chairman’s public proposal suddenly breathed an air of legitimacy and some new life into the idea.

It also sparked major conflict.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Not surprisingly, Republicans such as Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas) quickly shot it down. “No good purpose is served by continuing to persecute those who served in the previous administration,” he told CNN. Indeed, Sen. Arlen Spector (R-Pa.), the Judiciary Committee’s top-ranking Republican, had told Reuters in January that “If every administration started to re-examine what every prior administration did, there would be no end to it,” adding, “this is not Latin America,” an apparent reference to countries such as Argentina, Chile and Guatemala that have examined their own legacies of abuse.

The talk is also making some Republicans nervous. Asked Thursday by TWI’s David Weigel at an event held at the Capitol Hill Club whether he was concerned that an investigatory commission could be convened, former Attorney General Alberto Gonzales saidthat“only a fool” would not be concerned about a commission like this “in this political town in this political climate.” The former attorney general said he would cooperate if such a body convened.

Leahy’s statements were quickly embraced by many Democratic lawmakers, however, including Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Russ Feingold (D-Wis.), and supported by legal advocacy groups such as Human Rights Firstand NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, which had both earlier proposed similar ideas. Most recently, on Thursday, the bipartisan Constitution Projectchimed in with a statement, signed by 18 different organizations and a range of former government officials including Thomas Pickering, former Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs; William Sessions, former federal judge and FBI Director; and retired Major General Antonio Taguba, all calling for President Obama to appoint a non-partisan commission to examine the legality of Bush policies related to detention, treatment and transfer of detainees.

Yet the proposal has also revealed deep divisions among Democrats, legal experts and human rights advocates. That’s because Leahy was suggesting not a prosecution, but an investigatory commission, something along the lines of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that would have subpoena power and could offer legal immunity in exchange for testimony. Its aim would not be accountability for criminal actions, but to “get to the bottom of what happened — and why — so we make sure it never happens again,” Leahy said.

But that “middle ground,” as he called it, may be problematic. Many legal experts believe that eschewing prosecution is not an option: criminal prosecution is required under international law.

“The only reason to have a commission of this kind is to avoid doing what we’re obligated to do under a treaty,” George Washington University Law Professor Jonathan Turley told Keith Olbermann on MSNBC last week. “It is shameful that we would be calling for this type of commission,” he added. “We’re obligated to investigate. It’s not up to President Obama. It’s not up to Sen. Leahy.”

Margaret Satterthwaite, director of the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at NYU School of Law, agrees. “Under the [international] torture convention we are obligated to investigate and then prosecute where there’s evidence of torture,” she said.

That’s also the view of Tom Parker, Policy Director for Terrorism, Counterterrorism and Human Rights at Amnesty International USA. “Truth commissions are a great first step. But if the United States really wants to eliminate the stain on its reputation caused by these abuses, it needs to prosecute those most responsible.”

British law professor Philippe Sands, author of the book “Torture Team: Rumsfeld’s Memo and the Betrayal of American Values,” recently told John Dean, a former White House lawyer for Richard Nixon, that the Obama administration’s failure to prosecute “may give rise to violations by the United States of its obligations under the Torture Convention.”

That’s a real concern, say many legal experts. And it’s grown more serious since Bush administration officials themselves have acknowledged that torture occurred. In January, Susan Crawford, the Convening Authority of the U.S. military commissions at Guantanamo Bay, withdrew war crimes charges against Mohammad al-Qahtani, saying that he was torturedby U.S. officials and can’t be prosecuted based on the resulting confessions. In December, former Vice President Cheney confirmed that he approvedthe use of waterboarding. During his confirmation hearings, Attorney General Eric Holder said in no uncertain terms that he believes waterboarding is torture.

Add to that the recent reportsthat the Department of Justice’s own internal watchdog has sharply criticized the agency’s legal memos authorizing abuse of detainees as not meeting minimum professional standards, and former Office of Legal Counsel director Jack Goldsmith’s statements in his book, “The Terror Presidency,” calling those opinions “deeply flawed” and “sloppily reasoned,” and the Bush administration’s strenuous defense in recent years that it was reasonably following the advice of legal counsel begins to crumble.

Given these statements and reports, a number of legal experts are saying that the Torture Convention requires the United States to “submit the case to its competent authorities for the purpose of prosecution,” as Sands put it. That’s been the position for months or even years by such legal advocacy organizations as The Center for Constitutional Rights and the American Civil Liberties Union. They stepped up their callfor independent prosecutionsafter the Senate Armed Services Committee released a bi-partisan report in December revealing that senior Bush administration officials were responsible for the abusive interrogation techniques. More recently, Manfred Nowak, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, appeared to endorse their view, saying in an interviewon January 19 with a German news program that “the United States has a clear obligation” to take action against Bush administration officials who violated torture statutes.

There’s popular support for that view as well.

A USA TODAY/Gallup Polltaken at the end of January found that close to two-thirds of Americans surveyed said there should be investigations into allegations that the Bush administration tortured terrorism suspects and wiretapped US citizens without warrants. Almost four in 10 favored a criminal investigation, and about a quarter wanted investigations without criminal charges.

That may be why more and more politicians are emerging, after months of gaping silence on the issue, to favor some sort of accounting for what happened.

House Judiciary Committee Chairman John Conyers got the ball rolling, proposing legislation in early January to create a blue-ribbon panel of outside experts to probe the “broad range” of policies pursued by the Bush administration “under claims of unreviewable war powers,” including torture of detainees and warrantless wiretaps. Although not calling for a special prosecutor, his plan does not rule one out. Conyers originally had only a handful of Democratic co-sponsors, but there are now 24, including Massachussets Rep. Barney Frank and New York Rep. Jerrold Nadler.

Even House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has expressed tentative support for the plan, although she hasn’t signed on as a co-sponsor. In an interview with Fox Newsin January, she endorsed a probe into the politicization of the Justice Department, though she notably did not say whether the Bush administraiton’s torture and rendition policies merit prosecution. Such an investigation could be embarrassing to Pelosi and other Democratics, such as Rep. Jane Harman (D-CA) and Jay Rockefeller (D-W.Va.), who were briefed by the CIAon its interrogation tactics.

On the Senate side, in addition to Leahy and Whitehouse, Senate Armed Services committee Chairman Carl Levin has supported an investigation, saying “there needs to be an accounting of torture in this country,” and Sen. Majority Leader Harry Reid has said he would support funding and staff for additional fact-finding.

President Obama, for his part, has remained carefully noncommittal. In his inaugural address he boldly proclaimed that “we reject as false the choice between our safety and our ideals.” Yet when asked about Leahy’s proposal at his press conference last week, he said: “nobody is above the law and if there are clear instances of wrongdoing people should be prosecuted just like ordinary citizens. But generally speaking I’m more interested in looking forward than I am in looking backwards.”

Of course, there’s great pressure on Obama and Congress from the right, and even from some centrist Democrats, to turn his back on the past. Joe Conason, a usually liberal journalist, wrote in Salon last weekthat Obama should create a purely investigatory commission and pardon anyone who testifies “fully, honestly and publicly”. That places him in the unlikely company of National Journal and Newsweek columnist Stuart Taylor, Jr., who last summercalled for essentially the same thing.

Republican lawyers David Rivkin and Lee Casey last week arguedvehemently against any form of investigation in the Washington Post, saying a truth commission would be constitutionally suspect, while a criminal investigation would be downright dangerous. “Attempting to prosecute political opponents at home or facilitating their prosecution abroad, however much one disagrees with their policy choices while in office, is like pouring acid into our democratic machinery,” they warned. “[N]o one is entitled to hound political opponents with criminal prosecution, whether directly or through the device of a commission, and those who support such efforts now may someday regret the precedent it sets.”

Still, with Democrats in the majority and Leahy’s proposal putting at least the idea of a Truth Commission on the map, the call for some sort of accounting is gaining momentum. And experts in in human rights law are increasingly arguing that a broad-based Truth Commission that does not rule out prosecutions can actually complement any more targeted prosecutions that the facts may require.

“I would say that both processes are a good idea,” said Satterthwaite, at NYU.”Under international law you have to do prosecutions, and for the victims you have to establish the truth. So the best way forward really is to do both.”

Experts caution, however, that due to the statutes of limitations for crimes such as assault and torture, a truth commission should not be used to hold up criminal inquiries.

“For people involved in torture and assault, unless death resulted, the statute of limitations probably has already lapsed on many of those claims,” said Chris Anders, legislative counsel for the ACLU, referring to some of the early abuses of detainees at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere in 2002 and 2003. (There is no statute of limitations for murder or for war crimes, but the time limit for prosecuting torture is eight years, and for other crimes it’s five years.) Although John Conyers has recommendedretroactively extending the relevant statutes of limitations to ten years for any crimes committed, that could prove even more controversial than prosecuting them.

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles