Iraqi Translators Fear Retribution

Documents obtained by TWI reveal Iraqi linguists working for the U.S. military could be in peril under new disclosure rules fostered by the Status of Forces Agreement.

Jul 31, 2020203.5K Shares3.3M Views

Documents obtained by TWI support claims by Iraqi translators that the shift of power toward Iraqi officials could put them in danger.

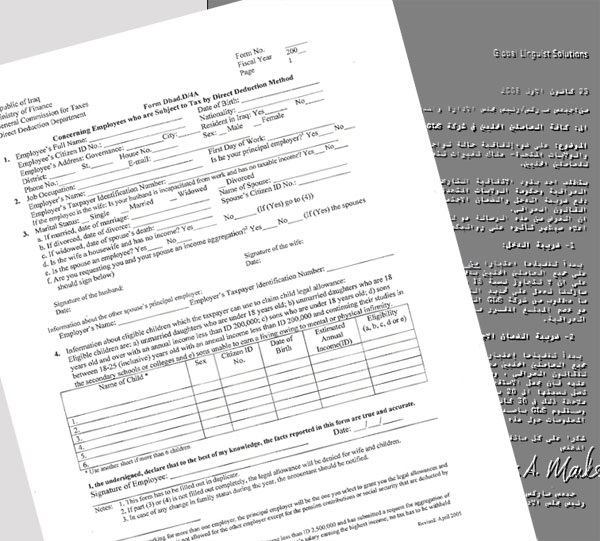

In the United States, it would be a mundane tax form, with standard provisions for cataloging an employee’s tax obligations. Full name. Citizen ID number. Address. Phone. Specifications about any children.

ButForm D/4a from the Iraqi Ministry of Finance is sending waves of anxiety through the community of Iraqis who work as linguists, translators and interpreters for the U.S. military in Iraq. For the “terps,” as many U.S. troops and diplomats call them, the form is a prelude to a disaster. Unless their identities are kept a closely guarded secret, they fear, they and their families will be hunted by insurgents, militias and death squads — many of whom are tied to or work for the Iraqi government — for collaborating with the U.S. military.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Several weeks ago, Global Linguist Solutions (GLS), the company that holds the contract with the U.S. military to provide translators, entered into negotiations with the Iraqi government about what their new obligations are for withholding employee taxes once the U.S.-Iraqi Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) — which, among other things, gives the Iraqi government increased authority over U.S. contractors — goes into effect. The company said emphatically that it has no intention of turning over identifying information for its roughly 7,000 Iraqi employees. “We’re not providing any personal identification information,” said company spokesman Douglas Ebner. “We have not done so up to now, and we’re not going to change.”

But many of these contractors don’t trust GLS to keep its word. Some are considering fleeing Iraq entirely, raising the prospect of U.S. service members losing their ability to talk and listen to Iraqis. “We either quit,” said Garrison, the pseudonym of an Iraqi interpreter, in an email, “or sign our own death warrants by turning the information [over] to the ministry.”

Terps go to extremes to safeguard their identities. Many are known to soldiers and marines by Anglicized names like Moe and Tommy and Big King Paul. When leaving U.S. bases to accompany troops on missions, it’s common for them to wear ski masks and wraparound sunglasses in the burning Iraqi heat, their hands covered in flame-retardant gloves so as not to leave behind so much as a fingerprint. Some don’t tell their families how they earn a living; others actually live on U.S. bases.

And for good reason: those who help the U.S. in Iraq are targets for insurgents, as are their families. While there aren’t available figures on how many Iraqis employed by the U.S. have been kidnapped or murdered, a well-received play, “Betrayed,” by the New Yorker’s George Packer, has chronicled the anxiety of collaborating with the U.S. in Iraq.

“There’s no future for us here,” a translator calling himself Big King Paul told me in Baghdad’s Khadimiya neighborhood in March 2007. “The terrorists know us. We can’t live in this country.”

In several cases, the terrorists are within the Iraqi government itself. Insurgents and militia members have infiltrated the ranks of the Iraqi police, and to a lesser extent, the Iraqi army — a systemic problem that retired Marine Gen. Jim Jones, now President Obama’s national security adviser, identified in an influential2007 report. Many political parties in Iraq, including aspects of the Shiite-dominated governing coalition, possess their own militias. And there remains a thriving kidnapping market in Iraq, creating a temptation among Finance Ministry bureaucrats to earn extra money by turning over case files on GLS employees to terrorists and criminals.

“Everyone knows the Iraqi police and all Iraqi security forces are either corrupt or [have] got something to do with militias or terrorist or insurgents,” said another Iraqi interpreter in an email.

Indeed, the very finance ministry that seeks employee identification information is run by a man named Bayan Jabr, who has ties to the Badr Corps militia affiliated with one of the major Shiite political parties, the Supreme Iraqi Islamic Council. In fall 2005, Jabr served as interior minister when U.S. forces discoveredthat the basement of the interior ministry was used as a torture chamber for Sunnis by Iraqi police officers. At the time, Jabr defended himself by saying, “Nobody was beheaded or killed.”

On Dec. 23, James “Spider” Marks, the retired Army two-star general who serves as CEO of GLS, sent GLS’ Iraqi employees a memorandum in Arabicinforming them of impending tax changes brought by the SOFA. “What is required from the company GLS to do as an employer is to deduct the determined amount from your monthly wages and pay it to the Iraqi government,” Marks wrote. The memorandum sparked a widespread fear among linguists, translators and interpreters that GLS would compromise employee identities as an aspect of compliance with the SOFA. A copy of the memo was acquired by The Washington Independent and translated into English. GLS would not provide the original English copy of the document but confirmed that TWI’s translation was “substantially accurate.”

Ebner, the GLS spokesman, confirmed that the company was in ongoing negotiations with the Iraqi ministries of finance and interior to determine the scope of its new legal obligations to the Iraqi government. But he said that employee concerns were unfounded. “The type of information pertaining to personal identification for employees is not going to be provided,” Ebner said. “We are fully confident that we’re going to work out procedures with the Iraqi authorities that both comply with the tax provisions of Iraqi law while fully safeguarding the personal identification information of our employees.” The company’s contract with the Defense Department, first awarded in 2006, is worth an estimated $4.6 billion.

According to Ebner, GLS site managers in Iraq have been instructed to tell Iraqi employees not to fear new company compliance changes. He attributed employee fears to the sensitivity of the issue. “In some cases, our site managers are speaking into the wind to individuals who are very concerned by this,” Ebner said.

Some GLS employees say that they’ve heard GLS denials but can’t afford to credit them. A promise not to disclose identifying information “may work with a friend or some other things but it will never work on this case,” said one interpreter. “We heard that the action was halted until further negotiations are reached,” said Garrison. “Absolutely, I fear for my and my family’s safety. The Iraqi ministries still have elements who can use this information to blackmail or threaten linguists or their families with. I have seen interpreters killed and displaced because their places of residence were identified by militants.”

A different interpreter emailed that he only worked for GLS because of their guarantees of employee confidentiality for a dangerous job. Now, that interpreter said, it is “just [a] matter of time” before insurgents are able to discover interpreter identities. “Iraq is no longer [a] safe place for us,” the interpreter said.

Another interpreter said that his site manager actually told him a different story. “ told me that they have to give my information to the [Iraqi government] because of the SOFA agreement,” the interpreter said. “I told the [project] manager in my unit that I’m willing to pay the taxes — 20 percent of my pay — but I don’t want them to give my identity information to the [government], but unfortunately the interpreters’ manager in my unit said ‘I’m afraid it is not a choice this issue is high high enough, the unit can not discuss this.’”

It is unclear what provisions of the Status of Forces Agreement mandate the additional legal compliance. While several portions of the accord suggest that Iraq has new authority to enforce its laws against U.S. security contractors like Blackwater or DynCorp — which is GLS’ parent company — none explicitly discusses Iraqi governmental power over Iraqi employees of U.S. companies. Ebner would not point to specific portions of the SOFA that prompted the recent negotiations between GLS and the Iraqi government.

For its part, the U.S. military said that the SOFA did not require companies to turn over Iraqi employee identification. “The Security Agreement does not, however, mandate any such disclosure with regards to U.S. contractors,” said Lt. John Brimley, a spokesman for the U.S. military command in Iraq. Brimley said that the military was not a party to negotiations between the Iraqi government and GLS.

Neither Ebner nor Brimley anticipated a linguist exodus because of the interpreters’ fears. “We cannot absolutely predict the future, of course, but no, based on what we have seen to-date, we do not anticipate significant loss of employees,” Ebner said. “We are confident we will continue to meet the linguist and interpretation needs of our military units in Iraq.” Brimley added, “The salaries of these positions are competitive with today’s market and thus we do not

anticipate any shortfalls.”

But some interpreters said they were already taking steps to leave Iraq. One interpreter, who said he lives with several colleagues, said in an email that he and his friends were preparing their paperwork and their passport information to flee the country. “We feel [we] got betrayed by GLS,” the interpreter said. “We are not going to continue working for GLS and absolutely we’re not staying in Iraq, we have to leave soon.”

He continued, “We all know the potential of getting killed if we stayed in Iraq, we all read history and know what we are talking about here. We never attempted [to] flee Iraq before, because most of us spend all their [lives] here! But not any more.”

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles