Of Fraud and Fairy Tales: The Memoir as Novel

So it happens again: another first-class storyteller dupes her agent, her editor, her publisher and a handful of high-falutin’, praise-bestowing reviewers

Jul 31, 2020205 Shares205.3K Views

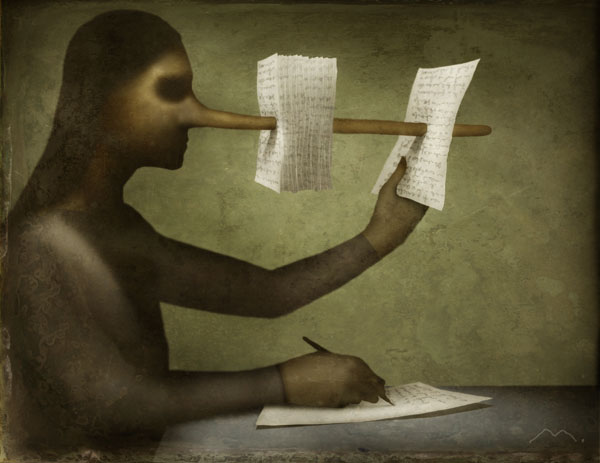

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

So it happens again: another first-class storyteller dupes her agent, her editor, her publisher and a handful of high-falutin’, praise-bestowing reviewers — including the often viperish New York Times critic, Michiko Kakutani — with a totally fake memoir, the poignantly named “Love and Consequences.” This leaves the rest of us scratching our heads and wondering just how many “literary” gatekeepers are asleep at the switch.

It’s hard not to titter a bit at their gullibility, especially in this case, especially if you hail from Los Angeles, as I do — the locale of this new tall tale. What we have here is a 33-year-old private-school graduate from Sherman Oaks in the San Fernando Valley, one Margaret Seltzer, claiming to have been a foster kid raised in drug-and-gang-infested South Central L.A. A whopper that would have, could have and should have been exposed in a nanosecond, with a few well-placed questions or phone calls.

No question, the declining book business is ever-hungry for the next big hit and when something looks this good, this juicy, this heart-tugging — half-white, half Native American girl-kid finds love in the hood with her surrogate mother, “Big Mom,” while running drugs for the gangs — it becomes an irresistible package. You just don’t do your basic background check which any decent fact-checker could do or should do in an afternoon. There’s big-time denial and big-time fear (gotta have a hit, gotta have a hit) at work here.

No question, too, memoirs are the thing of the moment, have been for a while now. We don’t have the time for fiction anymore. We don’t have the energy for it. We don’t have the patience for it. We want it real. Witness the popularity of so-called reality television — even though we know the “real,” in the best of circumstances, the most scrupulous of memoirs, is close at best, an approximation, a matter of memory.

Never mind. Give it to us as real as you can. Tell us who you hurt, who hurt you, what you snorted or shot up, when and where your Daddy molested you, your Mommy tried to stab you. Give us grit and redemption—always that combo or some variant of it: abuse and survival, self-abasement and triumph.

Make us feel good about ourselves (I didn’t have it that bad!). Make us feel good about America, about the promises of the Promised Land. These memoirs are our edgy new national fairy tales. See, you can survive anything here. Look at this foster kid. Wow. A victim and a toughie and a drug-runner and — the icing this time — a girl, and more, a girl who can spin literary gold out of her wounds. Street cred meets literary cred. What a find.

And what a fraud. What in the world went through Seltzer’s head over the years, three at least, that she was working on this book? Did she really think she was going to pull it off?

Did she think no one was going to notice somewhere along the way? Does she think that we all, in effect, live in a fantasy-world where one’s identity is negotiable. Push a little here, embellish a little there and, whammo, you are no longer a white private-school girl, but, by a true sleight of the imagination, an inner-city foster kid with a story to tell, rather, to sell. And more, a do-gooder who—on a web site and on the back-jacket copy of the book—talked about a foundation she had started to stem inner-city violence. Whoa—a foster kid with a golden tongue and a heart of gold. She became her very own fairy tale, a literary sociopath so deep in she could convince herself no one would notice—or perhaps care if they did.

Someone did notice: her very own sister, who called The New York Times after seeing a piece last week about Seltzer (that’s a great story waiting to be written, if our author wants to stab at the truth the next time). In her own defense after being outed, she said the most astonishing thing, a tip-off to her thinking. She said that she wrote the book while sitting in Starbuck’s in South Central and that she talked to gang kids there.

That’s it: slip into the locale, slip into the identity, like stepping into a movie screen. Maybe here, in L.A., that’s always the beguiling temptation — to re-imagine yourself, become the star of your own invented story. That’s what all those contestants on all those reality shows are doing, stepping over a border into dreamland—even “Survivor” dreamland where people pretend to starve. In effect, Seltzer simply cast herself as the ultimate survivor.

Perhaps down the road, she will try to work the TV redemption circuit—or she could do it on the Net with a Website. It’s a trick — but doable. She’d have to study James Frey’s attempt because it just didn’t work, didn’t play. He didn’t have enough heart, evidence enough self-abasement (speaking of self-abasement), certainly, to please Oprah — who had previously sung his praises and herself felt wrathful humiliation at his unveiling.

At least Seltzer didn’t cross her. That’s a career-ender. Not that Seltzer necessarily has one left, even as a novelist—which, of course, is what this should have been. Even though there’s a good chance (let’s be honest here) it would not have been published.

Meanwhile, as she licks her wounds or whatever she is going to do, she might take a look at the real casualties in the country’s inner cities, all those young black men in prison or dead on the streets — yes, girls, too. She spun them into her fairy tale. That’s her real shame. But then again, there is shame enough to go around.

Anne Taylor Fleming is a novelist, commentator and essayist for “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.” She is the author of a memoir, “Motherhood Deferred: A Woman’s Journey.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles