Waxman’s Watchdog Legacy

As chairman of the House oversight committee, Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) uncovered critical information about the worst reported abuses of power in the Bush administration.

Jul 31, 20205.5K Shares556.7K Views

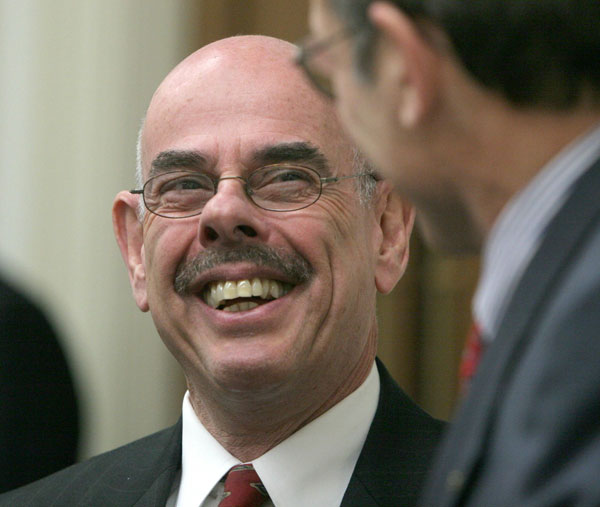

Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) (WDCpix)

?

Rep. Henry A. Waxman’s (D-Calif.) successful bid to become chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee closes the door on his brief but eventful tenure as Congress’ No. 1 watchdog over the executive branch.

After the Democrats took over Congress in 2006, Waxman, a member of the House since 1974, became chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. As head of the one congressional committee whose chairman can subpoena anyone, Waxman did what the committee under Republican leadership mostly hadn’t done — investigate waste, fraud and abuse in the Bush administration.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

The committee found plenty of corruption and incompetence in military contracting, Iraq war reconstruction, veterans’ health care, the implementation of clean-air and clean-water laws, executive branch politicization and financial deregulation, among other areas.

And its hearings made for some sensational headlines. Former CIA agent Valerie Plame testified on faulty pre-Iraq War intelligence. Little-known administration officials like Lurita Doan and Stephen Johnson became targets of national ridicule because of their on-the-job political activities. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan famously admitted under oath that his economic model was flawed and led to policy mistakes. And the committee obtained a pictureof imprisoned uber-lobbyist Jack Abramoff shaking hands with a smiling George W. Bush.

Waxman’s two years of news-making oversight raises a question: What difference did it make?

The answer, in part, is that the efforts of the Waxman-led oversight committee revealed critical information about some of the worst scandals and policy decisions of the Bush administration. In doing so, it helped check an administration that received little congressional scrutiny in its first six years.

Yet oversight probably came too late to significantly alter the course of the Bush presidency.

“Waxman was very effective and served as a deterrent to misbehavior,” said John Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College in California. “But when you’re investigating a lame-duck administration, the political impact is muted.”

Waxman, who represents Beverly Hills, established an early reputation in the House for crafting environmental, public health and consumer protection legislation. During the Bush administration, he added a second legacy — that of oversight czar. From his perch as the oversight committee’s minority leader, Waxman investigated Iraq war contractor Haliburton and faulty pre-Iraq war intelligence.

But the full committee, headed by Rep. Tom Davis (R-Va.), mostly disregardedthese and other reports.

The lack of congressional oversight from 2001 to 2006 may have hurt the administration. Former officials like Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and FEMA Director Mike Brown were excoriated only after their policies led to disaster.

“I think the Republicans in Congress did the administration a disservice,” said Barbara Sinclair, a professor of political science at UCLA. “If federal agencies know they may be looked at, the administration might not have gotten into trouble on a lot of things.”

When Waxman moved up to the committee’s chair after the 2006 elections, Time magazine called him “the Scariest Guy in Washington.” The New Republic declared “The Waxman Cometh.”

And he hit the ground running, holding four hearings in one week in February 2007 and wasting no time in using his subpoena powers.

Paul Bremer, former head of Iraq’s Coalition Provisional Authority, appeared before the committee to answer questions about the lack of Iraq reconstruction. The committee also delved into the abhorrent conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Center faced by returning Iraq soldiers.

A month later, Plame testified that the White House “carelessly and recklessly” revealed her CIA identity out of “purely political motives.” Three days after her testimony, NASA scientists accused administration officials of alteringd climate-change reports to cast doubt on global warming.

These early hearings helped establish the committee’s focus over the next two years. Iraq reconstructionwas perhaps its most scrutinized subject, particularly wartime contractors like Blackwater and former Haliburton subsidiary KBR.

The politicization of sciencewas also a subject the oversight committee frequently returned to, especially its effect on the Environmental Protection Agency’s failure to deal adequately with global warming.

But the committee wasn’t entirely fixated on administration wrongdoing. For example, in February 2008, it held hearings on the use of steriods in baseball,calling Roger Clemens to testify.

“The committee has very broad jurisdiction over all areas of government activity,” said Eleanor Hill, a partner at King & Spaulding law firm and former staff director of the Joint Intelligence Committee looking into the 9/11 terrorist attacks. “Waxman has made the most of that.”

The consensus among congressional experts is that Waxman did all he could — and it was the job of Congress and the administration to act on his oversight.

“He was the grand inquisitor,” said Ross Baker, political science professor at Rutgers University. “His job wasn’t to pass legislation but to hold hearings and do the oversight that was sadly neglected between 2001 and 2006.”

Waxman’s wide-ranging interests led him into areas that might have otherwise avoided scrutiny. Chief among these was the committee’s probe of the General Services Administration, whose head was illegally using her post to promote Republican candidates for Congress. At the end of a May 2007 hearing, Waxman called on Doan to resign. She stayed in her position for about a year.

But in other cases, Waxman was unable to get the information he sought from the administration, much less change its behavior. The most notable case involved Environmental Protection Agency head Johnson.

At a May 2008 hearing, Johnson repeatedly evaded questions from committee members about how the White House influenced the agency’s rule making on global warming and ozone standards. When Waxman asked Johnson to produce documents about his conversations with the White House, Johnson claimed executive privilege.

Atty. Gen. Michael Mukasey similarly claimed executive privilege when asked to provide a transcript of Vice President Dick Cheney’s interview with the FBI on the leak Plame’s CIA identity.

In the cases of Mukasey and Johnson, the White House appears to have succeeded in running out the clock.

Waxman wrapped up his chairmanship of the oversight committee with a flourish, though, holding five separate hearings into the causes of the financial crisis and what Congress should do about it.

The hearings exposed executive greed at Lehman Bros. and American Insurance Group, and prompted former federal regulatorslike Greenspan to admit they were “partially” wrong in their policy choices.

With Waxman moving over to the Energy and Commerce Committee, dramatic moments like Greenspan’s testimony may now be few and far between. His replacement as oversight chair has not been picked, and it’s not clear if Democrats will do what they said Republicans didn’t — keep a close eye on a president from their party.

“Waxman’s committee did show a virtue of a very divided government,” said Pitney, the Claremont professor. “And that’s vigorous oversight.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles