Time to Buy Gold Bars?

Jul 31, 202022.9K Shares850.1K Views

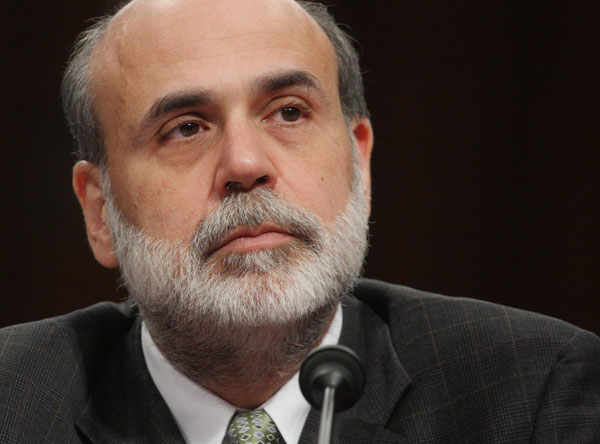

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke (WDCpix)

If Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke was hoping that the rescue of Bear Stearns would calm financial markets, he is likely to be disappointed. Last week’s Senate hearings on the details of the rescue brought more of the gory details into the light. Investors might be tempted to phone their neighborhood dealer in gold bars.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Bear Stearns, readers will recall, notified the Federal Reserve on Thursday, March 13, that it was on the point of declaring bankruptcy. The Fed provided a short-term loan, funneled through JP Morgan Chase, and over the following weekend engineered a shotgun marriage with Morgan. The Fed had to put up a $30 billion credit line, later changed to $29 billion, to induce Morgan to do the deal.

All the senior figures in the rescue, including Bernanke, testified, but the useful details come almost entirely from Timothy Geithner, president of the New York Fed, who was the point man in forcing a deal. Christopher Cox, the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and Bear CEO Alan Schwartz seemed to dismiss the entire episode as a mugging. Bear, in Cox’s words, was “a major investment bank that was well-capitalized and apparently fully liquid.” He makes its failure sound inexplicable. To Schwartz, Bear was just a victim of “unfounded rumors and attendant speculation…that grew into fear” about Bear’s solvency. Schwartz even managed to blame the Fed. He thought, he said, that he had 28-day loan, and discovered on Friday that it would be cut off Sunday night.

Though Geithner, like Cox, opened by filling the hearing room with a cloud of platitudes, he eventually got down to the real facts. After making the initial loan for “up to 28 days,” Geithner looked closely at Bear’s books, and decided he would “have been very uncomfortable lending to Bear.”

It didn’t require confidential information to get nervous about Bear.

Geithner called in Morgan because they were Bear’s clearing bank and. presumably, familiar with their portfolio. Morgan, too, when they took a closer look, became “significantly more concerned about the scale of risk” in a merger. Too bad they hadn’t exercised the same vigilance when acting as Bear’s clearing bank.

It didn’t require confidential information to get nervous about Bear. According to its SEC filings, Bear, on the most generous definition, was leveraged 20:1. Their 2007 trading books showed $138 billion of securities, funded with a $102 billion in short-term borrowing. A third of the portfolio was in mortgages, which could be valued, either wholly or partly, only by using Bear’s proprietary internal models. Lenders would just have to take Bear’s word for what they were worth. But there was a lot there to make a lender wary.

Bear’s shift toward shorter and shorter financing – a 47 percent increase in 2007 – was further evidence of the deterioration in its credit standing. Oh, and it had also entered into derivative arrangements where it guaranteed either to repay the principal par value on defaulting bonds or to guarantee specific security prices on $2.5 trillion of other investors’ assets. Nervous yet?

It gets worse. Bear put up $30 billion in “high-quality” collateral to support the $29 billion Fed line of credit to Morgan. (Morgan is on the hook for $1 billion.) How do we know it’s worth $30 billion? Because Bear said so. Fed releases and Geithner’s testimony stress that the loan is secured by “$30 billion in assets of Bear Stearns, based on the value of the portfolio as marked to market by Bear Stearns.” The supporting documentation(pdf) shows that the “assets” include unspecified “Unfunded Forward Commitments,” which, to the skeptically-minded, may just include a slug of those par value guarantees.

It’s also interesting that the Fed chose to characterize the mortgage securities that make up the bulk of the credit collateral as all “BBB- or higher.” BBB- is the lowest “investment grade” rating. Normally, one characterizes an investment portfolio by its average rating, not by its lowest. The “all BBB- or higher” wording suggests that the collateral is probably nearly all BBB-. There happens to be a trading index of BBB- bonds from standard residential mortgage-backed collateralized securities of the kind Bear is likely to own. As of last Friday, it was about 11 cents on the dollar.

Finally, despite the $29 billion in subsidy, JP Morgan asked for, and got, a waiver(pdf) of the Federal Reserve’s banking capital adequacy rules for the next 18 months. The implication is that once Morgan revalues the questionable Bear assets, the equity on the Bear balance sheet will disappear, and Morgan will find itself over-leveraged.

The blogosphere has changed the rules.

One bright spot in this dismal account is that it is no longer possible to brush such shameful episodes aside with a day or two of anodyne testimony. The blogosphere has changed the rules. A legion of dedicated, and knowledgeable finance bloggers has been diligently digging up all the details available to be dug. Readers who would like to plunge deeper into swamp should check out Yves Smith, Felix Salmon,Steve Waldmanand Alea.

But that is small comfort. The acrobatics of the Bear rescue suggest the depths of the abyss that our financial leadership has dug for us. Does anyone believe that this is the last time we will hear Fed sirens wailing in the night? And don’t we deserve a greater touch of candor on the part of officialdom? Bernanke, Cox and even Geithner, for much of his testimony, spoke of the crisis as if it was visited upon us from outer space. Is it about time for them to start pointing their fingers at themselves?

- Charles R. Morris, a lawyer and former banker, is the author of “The Trillion Dollar Meltdown: Easy Money, High Rollers and the Great Credit Crash.” His other books include “The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy” and “The Cost of Good Intentions,” about the New York fiscal crisis.*

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles