A Soldier’s Unnecessary Retreat

The McCain campaign’s decision to effectively concede Michigan to Obama makes no political sense because the GOP nominee enjoys key advantages in the state.

Jul 31, 2020101.6K Shares2.3M Views

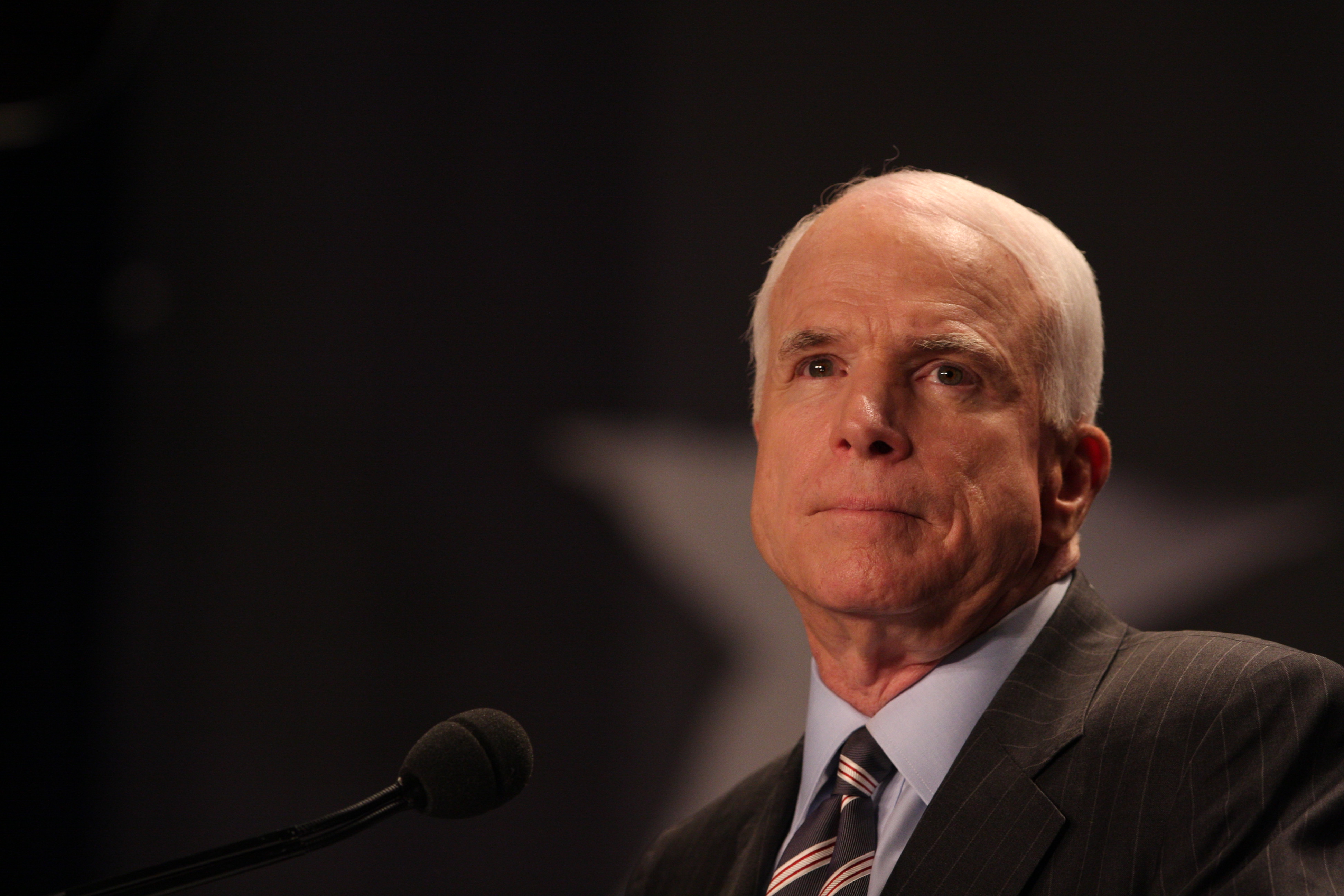

Sen. John McCain (WDCpix)

BIRMINGHAM, Mich.– Battleground no more.

For the past several months, the Republican and Democratic nominees for president have targeted this fading center of the Rust Belt, with its 17 electoral votes, as a winnable state — part of each party’s electoral strategy to take the White House.

Now, that plan for one ticket, that of Sen. John McCain and Gov. Sarah Palin, lies in smoldering ruins. As early as yesterday afternoon, reports began to filter out that the McCain campaign had suspended its efforts here and would be cutting staff as well as advertising.

McCain was essentially giving the state that George W. Bush narrowly lost, by five percentage points or less in 2000 and 2004, to Sen. Barack Obama.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

Before I traveled here, Debbie Dingell, the wife of the venerable Rep. John Dingell, talked with me about Michigan. A Democratic National Committee member, General Motors executive and political power in her own right, she explained why the state is so complicated and considered such a political prize:

“Michigan is the definition of a battleground state. It’s got a divided legislature. It’s gone back and forth on who its governors are. You’ve got two Democratic senators. But in a 15-member congressional delegation, six are Democrats and nine are Republicans. It’s a split state, and that’s what people forget. You have distinct urban agendas next to distinct rural agendas. You’ve got unions but also a strong religious community.”

To be certain, McCain’s move–or move-out–took all sides by surprise. As the darkened Detroit afternoon turned into a chilly night, political operatives and reporters alike were left a little like the characters in “Heroes” — disoriented and confused after the Haitian guy wipes away their memories.

For months now, Obama and McCain have been in a statistical dead heat — with the Democratic nominee only pulling ahead a little bit in the past few weeks. As a result, Michiganders have grown accustomed to frequent visits by the two candidates, who both promise to reroute the internal wiring of Michigan’s economic engine to make it a state that will thrive from the new, clean-energy-based economy. One half-expected McCain to ride out of Detroit in a Chevy Volt. As late as July, McCain told an audience here, “The state of Michigan, as it has in many elections in the past, will determine who the next president of the United States is.”

Now the Michigan GOP must travel alone — fighting in their leader’s name but without their actual leader. While polls over the past week have showed as much as a 10-point swing in favor of Obama, it’s precisely that volatility that made Michigan a state to stay in and fight for.

In a state where the Reagan Democrats were virtually born, there remains strong support for McCain despite recent events. But in the wake of the economic implosion, McCain has fallen behind Obama by an average of 7 percentage points in most polls.

McCain’s lack of authority on the economy and his fumbling response to the Wall Street meltdown have hurt him as the financial crisis seized the national psyche. He first said he would put his campaign on “hold” to help solve the problem in Washington, and then he returned to the hustings, which has led some voters to regard him as erratic. One report even cited that a fear among McCain campaign officials in Florida of a recent Obama surge in the Sunshine State contributed to the Arizona senator’s decision to quit Michigan.

But still, McCain defeated Bush in Michigan during their testy primary battle in 2000, and it is the home of a substantial number of white, working-class voters who Obama struggled to win over in the Democratic primary campaign. In short, this was a race McCain might have won.

“I certainly would have waited till after the debate tonight,” said Republican pollster Steve Mitchell before Sen. Joe Biden and Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin faced off in Thursday night’s vice presidential debate. “If Palin did well, that would have moved up [McCain's] numbers drastically. It’s a mystifying decision.

“It’s my understanding that it costs $1 million a week to run a campaign in Michigan,” Mitchell continued, “so it’s a multimillion-dollar decision. But it just seems like a really premature decision based on a couple of bad polls.”

McCain, by one account, had spent $8 million in television ads before pulling out.

According to many political experts, what McCain did by saying “no mas” to Michigan was to abandon a winnable race. It’s true that, to date, he hasn’t run the most efficient campaign here. More so than in some other states, the Obama campaign has been successful in linking McCain’s record to President Bush’s here.

In addition, going back to the Republican primary here earlier this year, McCain, to many Michigan business and union leaders, never really decided how to engage the auto industry. One day, he was the castigator; the next, he was ready to feel their warm embrace.

But these were supremely fixable things.

As much as McCain had going for him, several factors were also in play against Obama. Chief among them — and perhaps the one thing that many people seem most uncomfortable addressing — is race.

Late Tuesday morning, I sat down with William Black, the Teamsters’ political director in Michigan, in his office on Trumbull Avenue in Detroit. It was a cluttered space decorated with a “Hoffa” movie poster signed by Jack Nicholson and a photo of the union leader with Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton and Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm. Black was blunt about his biggest concern going into the November election.

“It’s the race issue,” Black said, leaning back in his chair, his arms folded over his chest. “It’s a concern for all of us. I don’t think it is for our age group — but it shows up in the older age groups.”

Black asked: “Will people put race over their pocketbook, over their financial well being? I think that’s the real issue here.”

Black had reason to worry. Two years ago, polls taken before the vote on a ballot measure that would have effectively eliminated affirmative-action programs in Michigan’s universities predicted a tight contest. The measure ended up winning 58 percent to 42 percent.

Moreover, Black said, the Obama campaign seemed at odds with itself. As the candidate of change who raged against the establishment, Obama had stormed into Michigan after not being present for the farce that was the Michigan primary, in which Clinton and Dennis Kucinich were the only candidates on the ballot. And his campaign hadn’t effectively used the machinery offered by the political establishment that has run Michigan for decades.

“[The Obama campaign] needs to do better outreach at the district level–I’ll tell you that right now,” Black said. “[It] needs to engage the John Dingells of the world and say, ‘John, what do you need?’ I’d like to see that. It’s not happening much, particularly down river or in Macomb County with the Reagan Democrats who need to be [targeted]. That would be the area I would be focusing on.

“John McCain is a guy you can never count out. Look at the Republican Party, look at what he did with Palin. I think he’s an amazing guy. I just can’t see him being president.”

But McCain is someone who many in Black’s own union ranks — a third of which he says are solidly Republican — could. That’s because they had seen the great promise of a young and energetic leader with limited executive experience who fizzled out as governor of Michigan.

Granholm stormed into office on the force of her personality and smarts and one term as state attorney general. In 2002, she ran for governor as the candidate of change, won and maintained a high approval rating as a new kind of Democrat.

Her approval rating remained strong until her first budget crisis. It’s been sliding with each subsequent crisis. With Michigan’s unemployment rate currently the highest in the country, Granholm’s approval rating hovers around 30 percent, equal to that of the Texan in the White House.

“[The McCain campaign] barely tied Granholm to Obama,” said Detroit News editorial page editor Nolan Finley when we sat down in his office late in the day Tuesday. “It ought to be doing that constantly. The Democrats have done a very good job of tying Bush to McCain,” added the influential conservative. “In this state, [the Republicans] could very well tie Obama and Granholm together — and do very well.”

As I’ve written before, one key reason that the presidential race remains close is that McCain is not Bush. His story–that of courage in combat, of standing against his own party when called for–has been effective when executed properly.

Indeed, given McCain’s image as a maverick, he could emphasize the idea of execution. Yes, he could say, the Bush tax cuts were a good idea, but they should have been followed by spending cuts. Yes, he could say, you hate the war in Iraq, but if I had been running things, we’d have been in and out.

“People aren’t looking for 10-point white-paper sheets,” Finley said. “They’re looking for a leader who can be confident. If he can come here and tell a story — his story — and show the confidence that he’s the guy who can lead them to a better place. He doesn’t have to come in here and say, ‘I’m going to do these six things, these eight things.’

Finley laid out how he would advise McCain to run here. “He shouldn’t give up on his foreign-policy issues just because of the financial crisis,” Finley cautioned. “He should remind people of that growing threat from Iran. Iran, Russia and other dangerous places are not going to go away.

“But he’s got to find himself domestically. One thing he could do today is say, ‘I’m going to appoint Mitt Romney as my Treasury secretary,’ and the people of Michigan would perk up and pay attention. He would have won Michigan if he’d put Romney on the ticket and said, ‘You take care of Michigan, Colorado and Nevada, and I’ll see you on Election Day.’ He needs Romney here. Whether Romney will do it or not is another question.”

Even without Romney on his ticket, McCain could still have advanced his position in Michigan with the GOP’s new political star, Sarah Palin. As Dingell has said, Michigan remains a divided state, a place where the Republican base still cares deeply about the issues that McCain holds dear–his stance against abortion, his opposition to gun control.

Palin would have drawn huge crowds from now until Election Day in the western part of the state, would have become a regular attraction on local newscasts and would have generated the kind of free publicity that a campaign relying on public financing needs. Gosh, golly, gee whiz, couldn’t you just see it? Wowzers!

But now that will not happen. The McCain campaign has all but shuttered its shop in Michigan, brushing off the state and conceding the ground that, only a few days ago, seemed one for the taking.

In coming days, McCain’s campaign advisers will explain their actions, provide a rationale that the climb was too steep, that resources were needed elsewhere. But should he lose on Nov. 4, the old soldier might look back at today as the beginning of the end, an opportunity lost. For once, McCain counted himself out.

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles