With voting rights groups reeling, new registrations decline

In Florida, 26.7 percent fewer new voters have registered this year than in 2006, along with 21.4 percent fewer in Maryland and 16.9 percent fewer in Tennessee.

Jul 31, 2020511 Shares511.1K Views

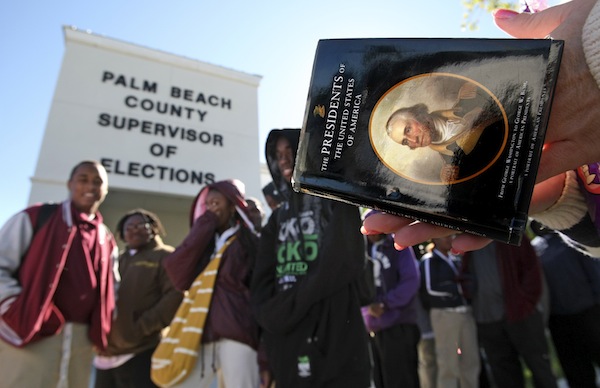

In Florida, 26.7 percent fewer new voters have registered this year than in 2006. (ZUMA Press)

After more than a decade of success expanding voter rolls, voting rights advocates are noting a disturbing trend in the run-up to the 2010 elections. Dramatically fewer groups are engaged in registering voters during the current election cycle than in previous midterm elections, and fewer voters, especially in poorer areas that are traditionally underrepresented and therefore the usual target of voter registration drives, are registering to vote as a result.

[Congress1] Registration patterns vary significantly from state to state, but 26.7 percent fewer new voters have registered in Florida this year than in 2006, along with 21.4 percent fewer in Maryland and 16.9 percent fewer in Tennessee, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a public policy and law institute at New York University. And while there’s no single cause for the decline, experts point out that many independent organizations are withering under a combination of public attacks by conservative activists alleging voter fraud and new state laws making it difficult for such groups to operate.

“A four-year wave of attacks on voter registration drives, both in terms of state laws that either shut down voter registration drives or made it too onerous to do it, and other public attacks have certainly had an effect,” said Wendy Weiser, director of the Brennan Center’s Voting Rights and Elections Project.

And while voter registration drives have languished, state governments aren’t picking up the slack. Voting rights advocates argue that many states aren’t adequately complying with requirements in the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 to register voters automatically at state agencies and keep their addresses up to date when they move. The result is a gaping hole in the country’s voter registration efforts that threatens to undo the positive strides that have been made over the last decade and a half.

The most obvious cause for the decline in voter registration is the shuttering of the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, or ACORN. At its height, ACORN had a budget of close to $35 million and was credited with registering approximately half a million voters in 2008 alone. Amid allegations from conservative activists that the group engaged in widespread voter fraud, Congress voted last fall to defundACORN, which received approximately a third of its budget in the form of government grants. The rest of the group’s funding soon dried up, and ACORN was forced to cease operations at its approximately 75 field offices soon thereafter.

But rather than rest on the laurels of their victory against ACORN, conservative activists have been emboldenedto seek outnew organizations engaging in voter registration drives and levy similar accusations against them, creating an increasingly hostile landscape for them to perform their mission.

“I wouldn’t underestimate the public attacks,” says Weiser. “It’s not a law prohibiting you, so it’s a little harder to demonstrate, but the chilling effects have nonetheless been palpable. People are nervous to do drives and support groups that do this kind of work.”

Tea Party groups, revved up by accusations made against ACORN in 2008, have workedto challenge voter registration drives and contest votes on election day in a number of states, including California, Wisconsin and New Mexico. But the clearest example of attacks launched against new groups seeking to register voters occurred in Harris County, Texas, where True The Vote, which is affiliated with the Tea Party group the King Street Patriots, dug through the county’s registrations and accused a voter registration organization called Houston Votes of engaging in widespread voter fraud in August.

The controversy centered on a number of voter registration forms filed by Houston Votes that were rejected because they were linked to vacant lots and people that did not exist. Many of these registrations, Houston Votes argues, had been made in 2008 and 2009 — before the group was founded and when many of the lots still had homes on them. But the damage had been done. King Street Patriots’ leader Catherine Engelbrecht allegedly referred to Houston Votes as the “New Black Panthers’ office”; Houston Votes responded by filing suit for defamation.

“When someone says you’re associated with racists that are trying to kill all white people, then it has a chilling effect on donors willing to give to your organization, which has an effect on the amount of work you can do. That’s pretty simple-minded stuff,” said Jim George, the lawyer representing Houston Votes. In recent months, the group has been forced to slow its activitiesto registering just 200 votes a day, down from over a 1,000 before the allegations were leveled.

But Tea Party groups pose only part of the problem for organizations hoping to launch voter registration efforts. While the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 requires states to make blank mail-in voter registration forms available to organized voter registration programs, many state legislatures, especially since the fear of widespread voter fraud began to rise among conservatives in 2004, have countered with various laws that place burdens on groups hoping to carry out that function.

These new laws, detailed in a reportby the Brennan Center, range from enacting stricter-than-usual reporting and filing deadlines for voter registration groups to shifting the cost of providing registration forms onto the groups themselves. In addition, many states have imposed stiff civil and criminal penalties on groups whose members are late or fail to comply with reporting, making engagement in the process overly burdensome or risky for small organizations.

The Republican-controlled state legislature in Florida, for instance, enacted a law so onerous that its constitutionality wassuccessfully challenged in courtin 2006 by the League of Women Voters of Florida. The legislature passed a new law in response, however, which a number of groups in Florida point to as the reason why registration efforts in their state are down more than 26 percent from 2006.

“The direct reason this year in particular is because of new legislation signed into law by the Republican state legislature that puts as many obstacles in place as possible as far as third parties hoping to register people to vote,” says Ron Mills, an area leader for the Broward County Democratic Party. “There are all these obstacles and reporting you have to do as if you are a campaign, even though you are a volunteer organization with few professional staff. … It’s got to where even the local Democratic executive committee in Broward County decided they didn’t want to go through the trouble, so we’re not qualified to register voters.”

New voter identification laws, too, are placing burdens on citizens’ ability to register to vote. Arizona, for instance, requires people to supply proof of citizenship to register to vote, and from 2004 to 2008, according to a report from Demos, the liberal public policy research organization, over 38,000 registrations were rejected as a result — despite court documents that indicated 90 percent were from residents born in the United States.

And the states, the Demos report also notes, are not filling in where outside voter drive efforts have fallen off. Many of them are failing to comply with the provisions in the NVRA that require them to keep up with voters’ address changes, which represent approximately a third of all registration activities in a given election cycle.

“If people move — and every four-year cycle it’s approximately 40 percent of the population in total who do so (and it’s more with poor populations) — one of the things that we found doing an investigation about states not complying with NVRA obligations is that they’re not updating registration addresses,” said the Brennan Center’s Weiser. “There was a huge increase in registration in 2008, and we worry with all the foreclosures and moving that a lot of folks on the voter rolls won’t be accurately reflected and might face problems when they try to vote.”

In the long run, a top-notch state voter registration system that complies with the NVRA and automates registration at public assistance agencies, schools and DMVs should be responsible for voter registration. In the meantime, said Weiser, “voter registration drives are the activities that fill that gap so they certainly perform a really needed function. Right now, there’s a very big hole out there.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles