Obama Unlikely to Use McChrystal Flap to Change Course on Afghanistan

The White House seems committed to Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s counterinsurgency approach -- and his most likely replacements share his outlook.

Jul 31, 202024.2K Shares638.2K Views

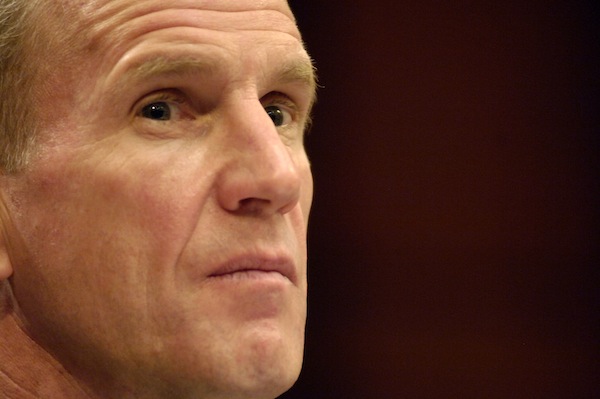

Gen. Stanley McChrystal (Louie Palu/ZUMApress.com)

By the time you read this, Gen. Stanley McChrystal may very well have lost his command in Afghanistan. McChrystal is headed to a White House Situation Room meeting with President Obama on Wednesday; Time’s Joe Klein reported Tuesday afternoon that the general offered to resignafter making disrespectful comments about senior Obama administration officials to Rolling Stone’s Michael Hastings. Whether Obama takes him up on his offer is a different story.

[Security1] And in some ways, it’s a less important decision than another one Obama must make: whether to take the opportunity to change the course of the administration’s strategy in Afghanistan. But if Obama has a chance to use the McChrystal controversy to overhaul his strategy, all signs indicate that he’s not interested.

The past two months in Afghanistan have been brutal. Since returning from a Washington summit with Obama, President Hamid Karzai acrimoniously parted ways with two of his top security officials, men trusted by the U.S. who believe Karzai’s attempts at outreach to the Taliban to bring the war to a close represent capitulation. A United Nations report released this weekend documented a rise in violence in southern Afghanistan ahead of a crucial attempt at pushing the Taliban out of Kandahar, the south’s most populous city. McChrystal had to slow down his push to provide what he calls a “rising tide” of security for Kandahar in order to secure buy-in from residents, as Karzai pledged his support for the operation at a mostly supportive local shura only last Sunday.

What remains unclear from any Kandahar planning is the effect even a successful operation will have on the overall strength of al-Qaeda’s allies in Afghanistan — and al-Qaeda itself, across the border in Pakistan. “There was good reason to drive al-Qaeda out of Afghanistan, but there’s no good reason to stay in the place,” said Douglas Macgregor, a retired Army colonel and a skeptic of counterinsurgency. “I don’t see any evidence [Obama's] suddenly going to summon the wherewithal to change course, but frankly this is an opportunity for him to do precisely that.”

If Robert Gibbs’ press briefing Tuesday was any indication, Macgregor has a point about Obama’s wherewithal. Gibbs, the White House press secretary, couched his and the president’s disapproval of McChrystal’s comments by questioning whether McChrystal was committed to implementing Obama’s strategy. “We’re here to implement a new strategy,” Gibbs said in his Tuesday briefing, and “that’s what we want everybody from the ambassador to the combatant commander to anybody else involved with this to focus on.” Gibbs emphasized that the mission in Afghanistan “is bigger than anybody on the military or the civilian side” — signaling that no officer is irreplaceable — and that it’s incumbent on the administration’s national security team “not to re-litigate” the internal autumn debate over Afghanistan strategy.

It was a surprising remark from Gibbs. McChrystal’s comments to Rolling Stone didn’t express any dissatisfaction with either the strategy or the resources he’s received to implement it. That’s probably because Obama ultimately embraced most of McChrystal’s favored approach: a rededication to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, backed by an increased complement of 30,000 new troops until July 2011, after which Afghan police and soldiers are to gradually assume primary security responsibilities. In the article, McChrystal merely sniped at his civilian superior, Vice President Joe Biden, who favored a more modest course in Afghanistan, and disrespected two of the senior State Department officials who are key to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan this year, Amb. Karl Eikenberry and Richard Holbrooke, the administration’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan.

But while McChrystal may not have meant to damage the strategy he helped create, the dismissive attitude toward the Obama team that he and his senior aides displayed to Rolling Stone put the president in a corner. “To take McChrystal out now and keep the deadline in place means that everything goes somewhat rudderless while time advances,” said a former senior U.S. diplomat who would not talk for the record because of the sensitivity of Obama’s impending decision. “That would be very deleterious to the policy. But to keep him in place would be harmful to the president’s authority. He has to decide what hit he wants to take.”

An additional factor: The short list for replacing McChrystal is heavy on counterinsurgents, further underscoring Gibbs’ emphasis on fidelity to the current strategy. Army Lt. Gen. David Rodriguez is McChrystal’s deputy, head of the International Security Assistance Force’s Joint Command, responsible for overseeing day-to-day military operations. Marine Gen. James Mattis, the head of U.S. Joint Forces Command, is perhaps the Marines’ leading counterinsurgency advocate. (A spokeswoman for Mattis told The Washington Independent on Tuesday, “General Mattis serves at the pleasure of the President, and is completely focused on his assignment as Commander, U.S. Joint Forces Command.”) Marine Lt. Gen. John O. Allen is the deputy commander of U.S. Central Command, where he serves under the military’s foremost counterinsurgency theorist-practitioner, Gen. David Petraeus. A choice that would indicate Obama intends to shift course would be Navy Adm. Eric Olson, the head of U.S. Special Operations Command, who recently criticized counterinsurgency for an insufficient focus on “countering the insurgents”— that is, battling them instead of securing populations from them — but Olson said at a recent conferencethat many of his criticisms are issues of degree, rather than wholesale rejection.

If Obama ends up making no changes to his strategy ahead of a scheduled December review and opts to keep his chastened commander, McChrystal will have to repair his relationship with his civilian partners if he’s to have any hope of achieving the unity of effort that counterinsurgency theory considers imperative. “I don’t know if I’d say it’s untenable, but he’s obviously in a difficult position,” said Mark Moyar, the author of a recent book on command in counterinsurgency who will arrive in Afghanistan next month to advise the U.S. military. “Most of [the offensive comments] came from his staff. Perhaps if he changed some members of his staff, it’d be possible to salvage” McChrystal’s command.

Sean McFate, a fellow with the New America Foundation and foreign policy adviser to the Obama campaign who used to work for McChrystal as a young officer with the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, said the administration’s approach in Afghanistan had yet to resolve a fundamental “disunity” that stretches beyond the personalities at the top of particular civilian and military billets. “The national security establishment has to decide if this is ultimately a civilian mission or a military mission,” McFate said, echoing a discarded proposal last year to appoint an official to oversee the implementation of both civilian and military aspects of the strategy. The Rolling Stone article “points to a fallacy of the ‘whole-of-government’ approach. It’s not clear if it’s civilian or military, and it’s certainly not both.” McFate made it clear that he has not spoken to McChrystal in years.

Officials and analysts cautioned that not all of the 30,000 surge troops have yet arrived in Afghanistan, making firm judgment on the strategy’s prospects ahead of December premature. Administration officials pledged last year that as they implement their strategy, they will take “a hard look at the strategy itself” in a review scheduled for December, as Defense Secretary Robert Gates told Congress. But last week, Petraeus and Undersecretary of Defense Michele Flournoy played down the importance of the review, characterizing it as a more aggressive version of the monthly administration-wide examinations of progress — which McChrystal will attend on Wednesday.

In his only public comments on Tuesday ahead of meeting with McChrystal, Obama said his decision would be “determined entirely on how I can make sure that we have a strategy that justifies the enormous courage and sacrifice that those men and women are making over there, and that ultimately makes this country safer.”

But that only begs the question of whether that’s Obama’s current strategy or some alternative. In Kabul and Islamabad, the former diplomat said, the U.S.’s chosen Afghan and Pakistani partners are looking for guidance as to the meaning of Obama’s July 2011 timeline, regardless of how often administration officials have publicly stated they want “long-term partnerships” with both Afghanistan and Pakistan. “Is it a conditions-based start of a slow process [of withdrawal], as Petraeus and Flournoy said, or is it more [in line with] quotes from Biden and impressions given by the president stressing the deadline” as the beginning of the end of the U.S. military presence in the country, the diplomat asked. “That’s a strategic question, one that only Obama can ultimately provide guidance on.”

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles