Buffett Defends Credit Ratings Agencies, Concedes System’s Flaws

The so-called Oracle of Omaha largely shifted the blame from himself and Moody’s, in which Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway is a major stakeholder.

Jul 31, 202063.9K Shares1.9M Views

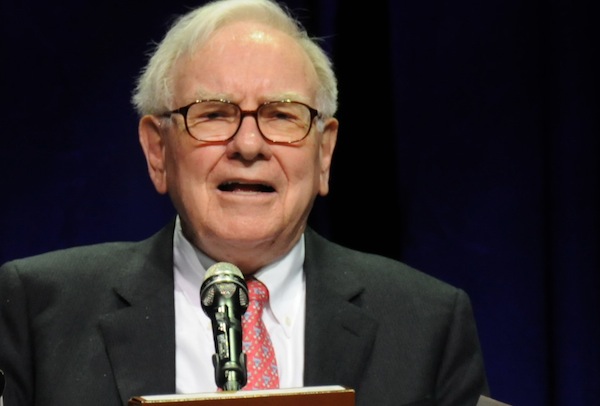

Warren Buffett (Xinhua/ZUMA Press)

Testifying before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission this afternoon, Warren Buffett — the legendary value investor who heads Omaha-based investment giant Berkshire Hathaway — defended the behavior of the country’s credit ratings agencies and his own role in them, while acknowledging that the model under which they operate creates a flawed system of incentives.

[Economy1] The FCIC, now notorious for its grilling of Wall Street executives, mortgage originators, government regulators and others complicit in the boom and bust, summoned Buffett to discuss the ratings agencies, which assess the chance that a financial product will default and assign it a grade that determines its price and risk. Berkshire Hathaway is a major stakeholder in Moody’s, one of the country’s two main ratings agencies — a lucrative duopoly that gave wildly inaccurate assessments of mortgage-backed securities before the crash.

As a stakeholder, one might have expected Buffett to defend the industry. And he did to a certain extent, arguing that Moody’s executives were not negligent and do not deserve to be fired, for instance. But he also undercut his own defense, noting that he “hates” the ratings agency business model and seemingly admitting that he invested in Moody’s for its profitability rather than its soundness. It made for an anemic stand for a business on the verge of major regulatory changes.

The so-called “Oracle of Omaha” largely shifted the blame from himself and Moody’s, arguing that systemically important financial firms that require government life support should have their shareholders wiped out and managers fired — but not Moody’s. And he did not acknowledge the ratings agencies’ unique role in precipitating the financial crisis, instead saying that Moody’s main mistake was to miss the trillion-dollar housing bubble along with “the rest of America.”

He actually had to be compelledto testify before the commission, declining two invitations before the FCIC subpoenaed him, saying, “YOU ARE HEREBY COMMANDED to appear and give testimony.” Still, the 79-year-old appeared unruffled and energetic, dressed in a dark suit and a red tie, seated alongside the chief executive officer of Moody’s, Raymond McDaniel.

Bill Thomas, the vice chairman of the FCIC, broke the tension in the room as he opened his questioning. “Notwithstanding the subpoena, I want to thank you for coming,” he began.

Buffett quipped back, “I want to thank you for the supboena!”

But the exchange soon became heated, with Buffett providing defensive and gruff answers to questions. Phil Angelides, the head of the FCIC, said that he had found “a lot of fingers pointing away” and “very little self-examination” at the credit ratings agencies. There were “significant failures in the product your company offered,” he said, and ratings “proved to be highly defective, not just by a small measure, but by a large amount.”

Angelides added, “If we flipped a coin, it would have been five times more accurate” than Moody’s ratings of structured products — 90 percent of which needed to be downgraded.

But Buffett said that Moody’s just made the same “mistake that 300 million Americans made” and that he did not believe its business model should change or its management should be fired. “Rising prices are a narcotic,” he said, a narcotic that intoxicated investors including himself.

Angelides pressed him on whether he should have seen the housing bubble, given that government regulators and market participants started sounding the alarm in 2004. “The Cassandras were there,” Buffett conceded. “But who was going to listen to [hedge fund investors] John Paulson in 2005 or 2006 or Michael Burry?” (Both Paulson and Burry called the bubble early and shorted the housing market, making billions as the economy collapsed.) Buffett said, “I recognized something pretty dramatic going on,” but he thought it was a “bubblette” rather than a “four star” bubble.

He also said that while he recognized real faults in the credit ratings business, he did not think that changing the model was necessary. “I hate issuer pay,” he said, describing the system by which the companies that produce financial products pay agencies like Moody’s to rate them — a conflict of interest at the heart of the business, as financial firms pressure agencies to give them better ratings and shop around for triple-A marks.

But Buffett said that he did not think anything else would work better. When asked whether the United States should adopt Sen. Al Franken’s (D-Minn.) proposal to have the government assign a rater to a financial product, he demurred. “I suppose it could happen,” Buffett said. “I’m not arguing this is the perfect model. I’m just saying it’s hard to change.

“The wisdom of somebody picking out raters — is that going to be perfect? I don’t know,” he continued, noting that the Nebraska insurance authorities tell him which ratings agencies he needs to hire to rate his products.

At another point, Angelides criticized the “very structure of credit rating agencies,” saying, “It does seem in the end, there’s lots of upside but very little downside” if Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s misrate financial products. “I think much of corporate America is tilted that way,” Buffett said, before wanly arguing, “We’ve seen significant downside” due to hits to Moody’s stock price.

Buffett also acknowledged that he personally has little investment in accurate ratings. “We hope for misrated securities, because it gives us a chance to earn a profit,” Buffett said. “I think they misrate us! [Moody's] have us a notch below Standard & Poor’s.”

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, the Republican former director of the Congressional Budget Office, repeatedly noted that Buffett’s testimony showed that ratings agencies were profitable due to their duopoly, rather than the usefulness of their ratings. Buffett did not disagree, instead noting that Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s ability to “set prices” — to somewhat arbitrarily name the fee for a rating, due to a lack of competition — made it an attractive business.

Buffett conceded that as an investor, he considered the duopoly “a wonderful economic model for the business.” And he added that Berkshire Hathaway does not rely on credit ratings agencies to analyze financial products, instead doing its own due diligence in-house.

He later said that ratings agencies might function best as a monopoly. “If there were 10 ratings agencies, all equally well-regarded [and] all acceptable to the market, they would compete on price, laxity or both,” he said. “If there were just one ratings agency, they would have no reason to compete.” He also noted that Berkshire Hathaway is reducing its stake in the company.

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles