Military Commission Hearing Adjourns With Mixed Results

There was a taint in this case, back from Bagram, says Omar Khadr’s attorney. That taint is still there, and the government cannot get away from it.

Jul 31, 202063.6K Shares1M Views

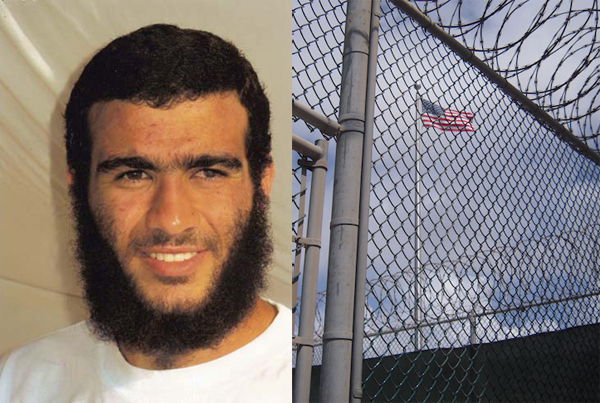

Omar Khadr and the Guantanamo Bay detention center (ZUMA, Spencer Ackerman)

GUANTANAMO BAY — Two weeks’ worth of testimony in a pre-trial hearing for the military commission of Omar Khadr, a 23-year old Canadian detained by the U.S. for nearly eight years, ended Thursday with two major declaratory statements. One was from the first man ever to interrogate Khadr, who testified that he threatened then-15 year old detainee in 2002 with rape and even death. The second was from the chief prosecutor in both Khadr’s case and the military commissions, who told reporters that the commissions “produce justice” and “produce fairness.”

[Security1] Testifying from a remote location, a former interrogator at the Bagram detention center in Afghanistan, identified to the court only as Interrogator #1, said that on August 12, 2002, he became the first U.S. military officer to interrogate Khadr, who was then restrained to a stretcher after suffering near-fatal gunshot and shrapnel wounds during his capture two weeks prior. Khadr, he said, was untruthful, providing Interrogator #1 with misleading statements, including about his identity. A few days later, Interrogator #1 began using techniques that he said were designed to illicit fear from the young detainee.

One of them involved telling a “fictitious story” to Khadr at an unspecified date in either September or October 2002, something Interrogator #1 said the interrogators at Bagram came up with after noticing Afghan detainees were “terrified of getting raped and general homosexuality.” According to the story, a “poor little 20-year old kid” found to be lying to interrogators about trivial matters was sent to a U.S. prison, where “four big black guys” and “big Nazis” eye up the fictitious detainee and the black inmates rape him in a shower — a brutalization that proves to be fatal. Army Col. Patrick Parrish, the military judge in Khadr’s military commission, said at the end of hearing, “I will stipulate as fact that the rape [threat] was said.”

Interrogator #1 later pled guilty to abusing a different detainee in a court martial and served five months in prison.

Threatening a detainee with death is a potential war crime under the Geneva Conventions. Interrogator #1′s free and open testimony raised questions — cited by the defense — that the government provided him with immunity, even though he was a defense witness. But Joe DellaVedova, a spokesman for the Office of Military Commissions, stated categorically that Interrogator #1 “did not testify today under immunity.”

Barry Coburn, Khadr’s lawyer, decried Interrogator #1′s account as an “implicit, perhaps really explicit, sort of a death threat” against his client. Eight previous military and law-enforcement officials who interrogated or questioned Khadr have said that Khadr — who is charged with the murder of Army Special Forces SFC Christopher Speer and with material support to terrorism — was a forthcoming and compliant detainee. Most of them talked to Khadr after Interrogator #1 did: one of them, FBI Special Agent Robert Fuller, may have interviewed him contemporaneously with the rape and death threat, and another, known only as Interrogator #2, participated in the first interrogation of Khadr in support of Interrogator #1.

Coburn and his team hope that Parrish considers that sequence to be as crucial as they do. The purpose of the last two weeks’ proceedings has been to determine whether statements Khadr made to his interrogators occurred in an environment so coercive as to render them inadmissible before the commissions, if and when Khadr’s case ultimately goes to trial. If Parrish rules that Khadr’s statements are considered inadmissible, then other detainees facing charges before the commissions may seek to have their own statements to interrogators excluded. While the commissions do not consider precedent to be as controlling as federal courts do, a favorable outcome for Khadr in the suppression hearing could still jeopardize a system that the Obama administration and Congress consider to be a necessary tool for trying terrorism detainees.

“There was a taint in this case, back from Bagram,” said Kobie Flowers, Coburn’s partner in representing Khadr. “That taint is still there, and [the government] cannot get away from it. Interrogator #1 brought you that in full color.”

Both Khadr attorneys cast doubt on the military commissions’ ability to provide justice for their client. “The system, the process” has been found “woefully lacking,” Coburn said. Flowers, formerly a federal prosecutor, denounced the government’s use of “secret evidence” assembled from Khadr’s interrogators, dozens of whom the defense has not been able to interview.

Navy Capt. John Murphy, the chief prosecutor for the military commissions and a prosecutor in Khadr’s case, dismissed the defense’s characterization of the state of the case during a press conference after the hearings recessed. “We are ready to move forward with our case. We are ready to go to trial,” Murphy said. Over the last two weeks, both the government and the defense have publicly confirmed that negotiations are ongoing to settle Khadr’s case out of court. Murphy said he is “generally confident in our case,” a confidence that “grows every day.”

Defending the military commissions as “part of our national legal structure,” Murphy denied that their viability was threatened if Parrish strikes Khadr’s statements to interrogators from use at trial. “Every case is assessed on its own unique facts,” said Murphy, a Naval reservist and federal prosecutor in civilian life. “I think what you see is a very fair process in terms of assessing the admissibility of these statements. I often think at times if you took away the uniforms and you didn’t realize we were at Guantanamo Bay and just walked into the middle of these proceedings, you would think you were in a traditional courtroom.”

Tom Parker, the director of Amnesty International’s counterterrorism and human rights program, disagreed with Murphy’s defense of the commissions. “I’m not entirely convinced the defense has had a completely fair shake,” Parker said, citing the difficulty the defense has had in gaining access to interrogators who spoke with Khadr, and the government’s repeated and successful attempts to suppress testimony about the general tenor about detainee treatment at Bagram and Guantanamo during Khadr’s detention in both places.

Parker cited Obama administration statements that raise the prospect of continuing to detain someone even after a court or a military commission acquits them. “The fear is that if he’s not convicted here, you know what the government’s position is, you’ve heard it in court: they will presumably decide to hold him,” Parker said. “They’re confident in their case, they don’t think it’s been diminished in any way, Capt. Murphy gets more and more confident every day. So I think we have to assume that if he’s acquitted, it’s quite likely that the government would then exercise this unconstitutional right that they now assert.”

In congressional testimony last July, Jeh Johnson, the Pentagon’s general counsel, saidthat the government’s right to detain someone “under the law of war” exists “irrespective of what happens on the prosecution side,” raising the prospect that the government could continue to detain someone even after acquittal. And Attorney General Eric Holder pledged last month to work with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC)on a statute to hold some terrorism detainees indefinitely without trial.

Shortly after the pre-trial hearing recessed for the week, the Pentagon announced that four journalists — Carol Rosenberg of the Miami Herald, Paul Koring of the Globe & Mail, Michelle Shephard of the Toronto Star and Steve Edwards of Canwest — would be barred from returning to Guantanamo Bay after they published the name of Interrogator #1. The reporters in question all used public evidence entered into trial to determine the identity of Interrogator #1, as did several of their colleagues who did not receive a ban, including The Washington Independent. Statements releasedby their news organizations vowedto appeal the ruling, which Shephard, author of a biography of Khadr, called “absurd.”

Ironically, Col. Dave Lapan, a representative of the Office of the Secretary of Defense who issued the ban, justified the ban in a letterby saying the reporters all “mention[ed] ‘Interrogator #1′ by his real name,” thereby publicly confirming Interrogator #1′s identity himself.

Parrish will likely not decide whether any or all of Khadr’s statements to interrogators must be stricken from the government’s case until at least June. On Monday, he ordered that the government can proceed with a mental-health evaluation with Khadr anticipated to last four weeks — after which the so-called suppression hearing will resume, as the defense presents its own mental health experts. Next week, Parrish will issue a ruling formally setting a schedule for Khadr’s military commission to begin.

Rhyley Carney

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles