Coal Country Lawmakers Stay Silent on Mine Safety Debate

Bruce Watzman, spokesman for the National Mining Association, told Senate lawmakers Tuesday that no new legislation is required to prevent the next mining tragedy.

Jul 31, 202019.1K Shares1.2M Views

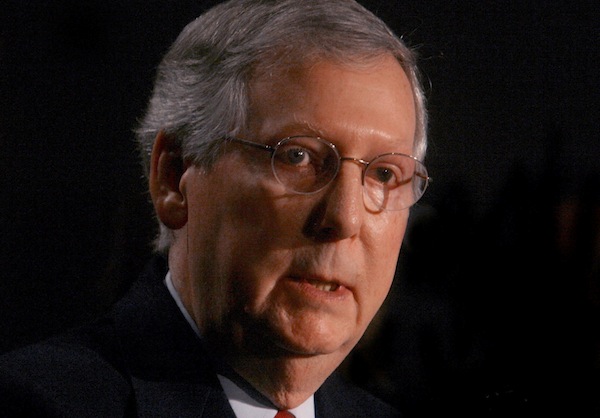

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has not addressed the need for mine safety reform in the wake of the Upper Big Branch explosion. (Zuma)

Wednesday’s fatal collapseat a Western Kentucky coal mine is a stark reminder that mine safety is hardly an issue peculiar to one state or one company. But you’d never know it based on the reaction from a long list of coal-country lawmakers.

Despite back-to-back-to-backfatal accidents at Appalachian coal mines this month, most regional lawmakers remain reluctant to enter the emerging debate over what’s gone wrong, and whether Congress should step in with new laws to protect the nation’s miners.

[Congress1] Their silence highlights the tremendous influence of coal companies in the Appalachian states, among the poorest in the country, where the industry supports tens-of-thousands of jobs and contributes hundreds-of-thousands of dollars to convince lawmakers that things like new safety measures are unnecessary. Indeed, throughout Kentucky and Virginia, the lawmakers most reluctant to weigh in on mine-safety policies this month are also those who’ve accepted the most money from the industry over the years.

That hesitancy to confront Big Coal — glaringin the wake of the deadly April 5 blast at Upper Big Branch, when West Virginia’s lawmakers were the lone Appalachian voices calling for reforms — remains on display this week, even after a roof fall at Kentucky’s Dotiki Mine killed two more miners Wednesday. Though the companies were different — Virginia-based Massey Energy owns the Upper Big Branch, and Alliance Resource Partners, based in Oklahoma, owns Dotiki — both projects have run up a long list of safety violations this year (see hereand here).

A third fatal accident — at a West Virginia mine owned by International Coal Group – occurredApril 22. All told, Appalachian coal-mining accidents have claimed the lives of 32 miners in April alone.

No matter.

Although Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) took to the chamber floor Thursday afternoon to offer condolences and prayers, there was nothing in his brief speech to indicate that the nation’s mine-safety policies might be failing miners, or that Congress has any responsibility to intervene. And his office, which had declined to answer questions along those lines in the wake of the UBB blast, went silent again Thursday.

“For now, we can only hope that their efforts are successful,” McConnell said of the rescuers searching for a missing miner, who would later turn up dead. “I ask my colleagues and the American people to keep the miners, their families, and the rescue workers in their prayers.”

The other members of Kentucky’s congressional delegation didn’t go even that far. Rep. Ed Whitfield (R), who represents Webster County, where this week’s roof collapse took place, has, as of this writing, no mention of the accident on his website** (although it does contain a statement — issued just hours before Wednesday’s accident — attackingthe Obama administration for being too tough on the coal industry). Whitfield’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

McConnell and Whitfield are hardly alone. The offices of Sen. Jim Bunning (R-Ky.), Rep. Hal Rogers (R-Ky.) and Rep. Rick Boucher (D-Va.) have also declined repeated requests for comment on mine safety in the wake of the Upper Big Branch disaster — a silence that’s continued this week following the disaster in Webster County. All three lawmakers represent prominent coal-producing districts where mining companies have racked up thousands of safety violations this year alone.

For example, Pike County, Ky., represented by Rogers, is home to Freedom Mine #1, a Massey-owned project that’s tallied more than 400 safety citations since Jan. 1. Among the violations are a number involving problems with mine ventilation systems and the accumulation of combustible materials — the same combination suspected to have caused the explosion at the Upper Big Branch. Dozens of those problems were deemed “significant and substantial,” indicating that they are “reasonably likely to result in a reasonably serious injury or illness.”

Another example: Boucher represents Tazewell County, Va., which is home to the Tiller No. 1 Mine. That Massey-controlled project has been cited more than 70 times this year for safety infractions, including vent problems, accumulations of combustibles and a failure to maintain escapeways. Forty of those citations fell into the S&S category.

And the list goes on.

That the lawmakers representing these mines haven’t confronted the companies over their dubious safety records, critics argue, owes a great deal to the steady flow of money from the industry to those members. McConnell, for example, has accepted more than $486,000 from the coal mining industry over his career, according to the Center for Responsive Politics— far and away the most of any active Capitol Hill lawmaker. Rogers ranks second, with industry contributions totaling more than $241,000. Boucher stands fifth, having taken more than $186,000 from coal companies during his tenure on the Hill. And Whitfield’s career tallyof more than $100,000 places him eighth among all active members in the House.

Not that there aren’t exceptions to the reluctance of Appalachian lawmakers to discuss mine safety in recent weeks. Sen. Jim Webb (D-Va.), for example, though not a member of the Senate labor committee, submitted a statement to that panel when it met earlier this week to discuss mine safety. “We can — and must — do better by our miners,” Webb said, “when it comes to enforcing safety regulations and ensuring that companies don’t walk away from their responsibility to their workers.”

Still, Big Coal’s influence, combined with the industry’s oppositionto any new mine-safety regulations, means there will likely be a tough road ahead for the reform-minded lawmakers already pushing for stricter rules. Indeed, Bruce Watzman, spokesman for the National Mining Association, told Senate lawmakers Tuesday that no new legislation is required to prevent the next mining tragedy.

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles