Are We Facing a Jobless Recovery?

Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke announced last month that the recession was “likely over” and that the economy was in the early stages of a recovery. The problem is, many Americans don’t look around and see a recovery.

Jul 31, 202067.5K Shares1.5M Views

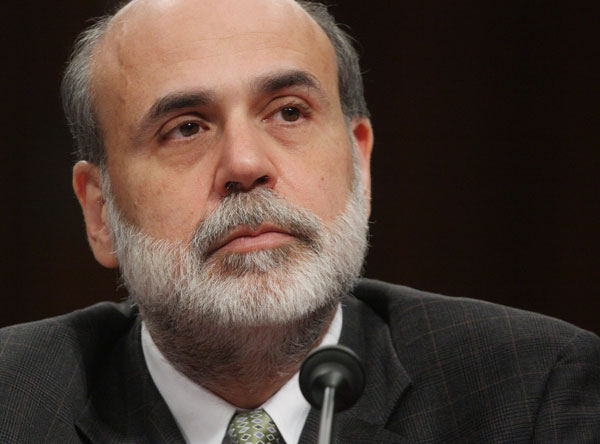

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke (WDCpix)

Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke announced last month that the recession was “likely over” and that the economy was in the early stages of a recovery. The problem is, many Americans don’t look around and see a recovery due to the still-abysmal unemployment rate. What’s scarier is that those numbers are probably going to get worse before they get better. The Congressional Budget Office predicts unemployment peaking at 10.2 percent next year and remaining at a very high 9.1 percent in 2011.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

“What people care about is numbers that affect their lives — employment, pay, housing. The story in almost all those cases looks bad,” said Dean Baker, director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “In one sense the recession will be over, but for all practical purposes, it still will be a recession for most people.”

In other words, we’re looking at a jobless recovery. “What it means is that the economy is recovering for Wall Street and business profits but it’s not distributing that prosperity effectively, and that’s not the recovery we need,” said Andrew Stettner, deputy director of the National Employment Law Project. “It’s not a true recovery until it lifts the fortunes of average Americans,” he added. Waiting for that could take a while: the Congressional Budget Office estimates it could take another five years to get back to America’s pre-crash unemployment rate.

Unlike recessions from roughly the end of World War II until the 1980s, a bounce-back in U.S. jobs isn’t going to come from the nation’s giant manufacturing sector cranking itself back up. While America still does produce goods both for export as well as for consumption at home, the 20th-century manufacturing-based economy has shifted to a service-oriented one, and roughly 70 percent of our economy these days is driven by consumer spending. As a result, recent recoveries have tended to be jobless ones in which the employment rolls take much longer to catch up with the rise in GDP that signals a recovery. After the 2001 recession, it took 17 quarters — more than four years — for the labor market to recover.

The severity of this recession as well as the enormous number of jobs lost is already creating a strain on the nascent recovery, and experts say it presents a number of challenges for average Americans as well as policy-makers. One of the most glaring is the issue of health care. The importance of the ongoing health care debate — and the need for reform — is highlighted by the plight of the unemployed when it comes to health insurance.

Currently, laid-off employees are eligible to remain in their employer’s group pool through the COBRA program for up to 18 months. Historically, many people who lose their jobs turn down the COBRA coverage because it requires individuals to shoulder the entire cost of the premium by themselves. In an acknowledgement that this is no ordinary recession, the federal $787 billion stimulus package includes a provision providing unemployed workers with a 65 percent subsidy of their COBRA premiums for nine months.

This is unprecedented, and yet many economists say it’s not nearly enough. “A lot of the people who start being unemployed aren’t reemployed after nine months,” Burtless said. The number of Americans on the jobless rolls for months or even years at a time is already swelling and expected to grow, which means it’s increasingly likely that the unemployed will run through their COBRA benefits by the time they land a new job. Even if a worker is lucky enough to land a job that includes health insurance (which is no guarantee these days, either), restrictions on pre-existing conditions kick in, leaving an untold number of Americans without a healthcare safety net.

Health insurance isn’t the only issue, though. “It’s a desperate situation because it’s going to be long term,” warned CEPR’s Baker. “Today you have people getting benefits, but people might be out of work for two or three years, and we’re not set up for having high rates of unemployment.” Baker points out that other developed nations are better equipped for a situation like this because of programs like long-term unemployment insurance, housing assistance and health care.

Prolonged unemployment is a double-whammy for those stuck without jobs for extended periods; not only are they out of work, but when the economy rebounds, they’re more likely to be passed over by the companies doing the rehiring in favor of people who have exited the workforce more recently. According to Lawrence Katz, a professor of economics at Harvard University, the unintended consequence of this escalation will be to push more workers into disability and early Medicare programs. “That becomes the only option and the difficulty with that is once people go on disability programs they basically never leave, which becomes very expensive,” he warned.

Benefits like unemployment payments are also facing a similar strain that’s likely to get worse before it gets better. Right now, laid-off workers in the states most severely impacted by the recession can draw up to 79 weeks of unemployment benefits. As with the COBRA subsidy, this is already an extension above and beyond the norm, but it’s not clear how much more of an appetite the federal government has to subsidize long-term joblessness.

There are a couple of encouraging signs that the government does understand the severity of the problem and is taking steps to address it. Support for a payroll tax credit, one oft-cited measure for increasing employment, is gaining support among both parties in Congress. One suggested version would give companies a credit of double the payroll tax for every employee hired or converted from part- to full-time. “We did a new jobs tax credit in the ‘70s that had some impact,” said Harvard’s Katz, adding that a broader wage subsidy would have a similar impact on the private sector but also offer employment support to nonprofits, as well.

The government could take a more direct role in boosting employment, Brookings’ Gary Burtless suggests. “I expect that if job creation is very anemic on private payrolls and continue to have a Democratic administration, there’s going to be a lot of initiative to somehow increase the share of the government’s stimulus efforts on job creation.”

It’s also possible that job-creation programs in stimulus bill may yet play a role in shoring up payrolls, although even pro-stimulus economists think that role will be minor. “It’s probably to date created between 700,000 to a little over a million jobs,” said CEPR’s Dean Baker. “It will make more of a difference, but it’s not big enough.”

There are still a couple of factors that could turn the tide in workers’ favor. Andrew Stettner points out that the stimulus-led investment in clean energy and “green” technology has the potential to put the U.S. back in the manufacturing game. “Right now, we’re borrowing and consuming. We need to move our economy more broadly to producing and inventing by investing in it to make it more competitive,” he said.

On a somewhat grimmer note, if America’s recovery lags behind that of our major trade partners or if the dollar is weak for a prolonged period, a surge in demand for exports could be a silver lining for the employment rate. Similarly, inventories in this country have been pared down so far that a big uptick in demand could lead to hiring, but since so much of what we consume comes from overseas, any employment boost there would be shared with other countries.

The worst-case scenario, says Brookings’ Gary Burtless, is that we experience a recession on par with the very steep one in 1981-82, but without the jobs recovery that followed. If this happens, Andrew Stettner of NELP predicts a societal fragmentation of nearly unprecedented magnitude. “I think you’ll start seeing a divided consciousness between the haves and have-nots by next year. Those who did lose their jobs and their savings will be increasingly isolated.”

Paula M. Graham

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles