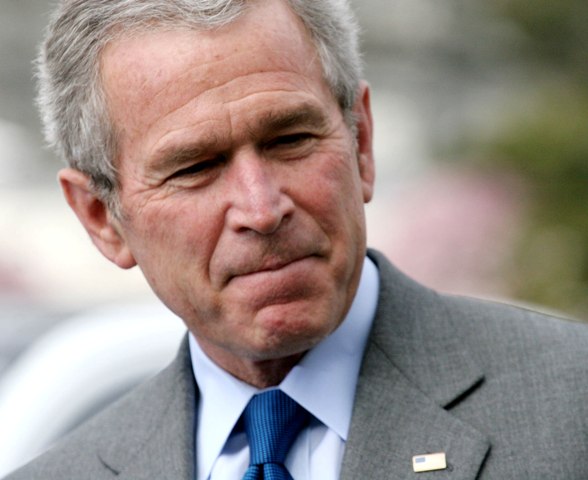

Pressure Mounts for Torture Prosecutions

When President George W. Bush wrote on February 7, 2002 that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions did not apply to al Qaeda or Taliban detainees, he took the first step down a slippery slope of legal interpretation that he and members of his administration may come to regret.

Jul 31, 20201.1K Shares556.7K Views

When President George W. Bush wrote on February 7, 2002 that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions did not apply to al Qaeda or Taliban detainees, he took the first step down a slippery slope of legal interpretation that he and members of his administration may come to regret.

Illustration by: Matt Mahurin

The release of the complete unclassified version of a Senate Armed Services Committee report on Tuesday, following the release last week of more Office of Legal Counsel memos that detailed the interrogation methods used by the CIA and their legal justifications, are ratcheting up the pressure on Congress, as well as on President Barack Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder, to initiate more in-depth investigations that may, some experts say, ultimately lead to criminal prosecution.

On Tuesday, President Obama did not rule outthat Holder might prosecute the legal architects of the abusive interrogation policies, and said he was open to a bipartisan congressional commission investigating the Bush administration’s use of harsh interrogation techniques and how the policies were developed. And European and U.N. officialsare increasingly saying that if the United States does not prosecute what appears to be a violation of the Convention Against Torture, to which the United States is a signatory, then European prosecutors may initiate prosecution themselves.

The release on Tuesdayof the complete Senate Armed Services Committee report makes turning a blind eye to the past even more difficult. That’s because the report concludes that in many respects, Bush administration officials ignored prevailing domestic and international law and the legal advice of U.S. military lawyers in developing the abusive interrogation policies.

Among its findings, the report concludes that the use of techniques such as stripping detainees of their clothing, placing them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads and “treating them like animals” was “at odds with the commitment to humane treatment of detainees in U.S. custody”; was “inconsistent with the goal of collecting accurate intelligence information”; “created a serious risk of physical and psychological harm to detainees”; and was justified based on legal opinions that “distorted the meaning and intent of anti-torture laws, rationalized the abuse of detainees in U.S. custody and influenced Department of Defense determinations as to what interrogation techniques were legal for use during interrogations conducted by U.S. military personnel.”

Some of the facts set out in the report strongly suggest that further investigation is warranted as to whether the legal conclusions were reached in good faith by the lawyers, and whether policymakers acted reasonably in relying on them. That’s critical to the defenseput forward by Bush administration officials such as former Attorney General Michael Mukasey and Vice President Dick Cheney, who have consistently defended the Bush administration’s conduct by saying they all reasonably relied on the good-faith advice of government lawyers.

The Senate Armed services report repeatedly calls that “good faith” into question.

“The report talks about Haynes disregarding the advice from JAGS [Judge Advocates General], and disregarding other legal opinions,” said Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights who has been calling for years for appointment of an independent prosecutor to investigate the Bush administration’s interrogation policies. “If you’re a prosecutor, that gives you something. That questions good faith.”

The Armed Services report concludes that “leaders at GTMO … ignored warnings” from lawyers within the Defense Department and FBI that “the techniques were potentially unlawful and that their use would strengthen detainee resistance.” It adds that Chairman of Jt. Chiefs of Staff General Richard Myers cut short the legal and policy review initiated by his legal counsel, which “undermined the military’s review process.” And the report finds that the conclusions reached about the legality of the interrogation techniques “followed a grossly deficient review and were at odds with conclusions previously reached by the Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Criminal Investigate Task Force.”

As one example, the report cites a meeting between Jonathan Fredman, chief counsel to the CIA’s CounterTerrorist Center, and GTMO staff about aggressive interrogation tactics. According to the meeting minutes, Fredman said that ”the language of the [torture] statutes is written vaguely … It is basically subject to perception. If the detainee dies you’re doing it wrong.”

Bush administration critics claim the committee report and OLC memos support their claims that senior officials knowingly flouted the law and used administration lawyers to justify it.

“The consistent story is that there was high-level pressure to authorize these things,” said Alex Abdo, a legal fellow with the National Security Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. “That certainly bears upon the question of whether DOJ lawyers were merely ratifying their bosses’ wishes.”

As Ratner puts it, “the facts on what they did and who they ignored in getting their legal advice is quite damning.”

The four Office of Legal Counsel memosreleased last week as part of a lawsuit filed against the government by the ACLU, in addition to previous legal memos released earlier, also support the view that the administration was not seeking objective legal advice, but justification of pre-ordained policies, say many legal experts.

The memos conclude, for example, that techniques such as slamming a prisoner repeatedly into a wall, confinement in a small box with insects, waterboarding up to 183 times, forced nudity in extreme hot and cold temperatures, and sleep deprivation for almost six days at a time are not only not torture, but don’t constitute even “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” in a constitutional sense.

Part of the reasoning, according to the May 30, 2005 memo, is that these things were done for a legitimate governmental purpose — to thwart another terrorist attack. But legal experts say that even if there was reason to believe that such tactics would be effective — which is itself not supportedby the evidence — the legal reasoning falls apart under both domestic and international law.

“There is no exigency exception to the law against torture,” says Abdo. “Even if it’s not torture, it would without a doubt be degrading and inhuman treatment. But it seems pretty inescapable that what was justified was torture. And that these lawyers should have known better. You don’t have to look very far in our history to show that waterboarding was something we prosecuted after World War II when it was used on our soldiers. So you can look at the memos and conclude this was not good-faith legal advice.”

Indeed, waterboarding has long been considered a form of torture, as Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse(D-R.I.) and others have noted. It’s even been referred to as torture in U.S. case law, most recently when U.S. Attorneys prosecuted a local sheriff for using the tactic in Texas.

“That’s nowhere mentioned in the memo,” said Abdo. “There’s no attempt to reconcile the U.S. past position on the technique with current authority.”

As the Armed Services Committee report notes, the problem begins with Bush’s decision early on that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions does not apply to the conflict with al Qaeda and the Taliban. Although the Supreme Court eventually said he was wrong, that didn’t happen until 2006 in the case of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. But many international law scholars insist that was an unsupportable position to take even back in 2002.

Common Article 3 sets a floor,” said Carolyn Patty Blum, an emeritus law professor at Berkeley School of Law and expert on international human rights law. “You can’t go below this. It’s basic to every person, be they civilian or combatant.”

Even if it didn’t, however, there’s the Convention Against Torture, the U.S. anti-torture law, the Torture Victims Protection Act and customary international law (which the OLC memos don’t even mention), all of which define torture and have been interpreted in a body of caselaw. “If you were doing a thorough job to try to understand what torture is, you’d be drawing from a much vaster body of law that exists, that’s used by all the major courts,” said Blum. “If your goal is to get a certain result, you wouldn’t do that.”

That isn’t to say that there aren’t ways of rationalizing a wide range of acts in the name of national security.

“There is a conservative instinct to try to say among some people that anything goes as long as you’re protecting the U.S. from terorrism,” said David Golove, a law professor at New York University School of Law and expert on international law and executive power. “I think that the notion that you can use tactics like waterboarding and extended sleep deprivation and hitting people against the walls, the idea that those are tactics that can be used under any circumstances for any governmental purpose is outlandish. That’s not to say that there isn’t case law that invokes the relevant government interest, but to say that justifies this conduct” — as some of the OLC memos do — “is taking it out of context. In no way have the courts ever suggested that these sorts of extreme tactics could be justified.”

Still, even if the legal conclusions the Bush administration relied upon were wrong, were they criminal? That depends in part on how they were reached.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know, about how this all took place, how this went up and down the chain of command,” said Blum. “Based on what we know now, it would indicate that the Department of Justice would be derelict in its duties to not follow the evidence where it might lead and initiate some sort of criminal investigation. Both of those who perpetrated it and those who ordered it — the relationship between the lawyers who were assisting part of a criminal conspiracy. Because that’s what we’re talking about here. A criminal conspiracy to violate the U.S. law against torture.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles