Gitmo Prisoners Pose Thorny Problem for Obama

Closing Guantanamo and ending the military commissions is the easy part. It’s what to do with the people imprisoned there that’s already presenting a political problem for the president-elect and his new administration.

Jul 31, 20206.9K Shares537K Views

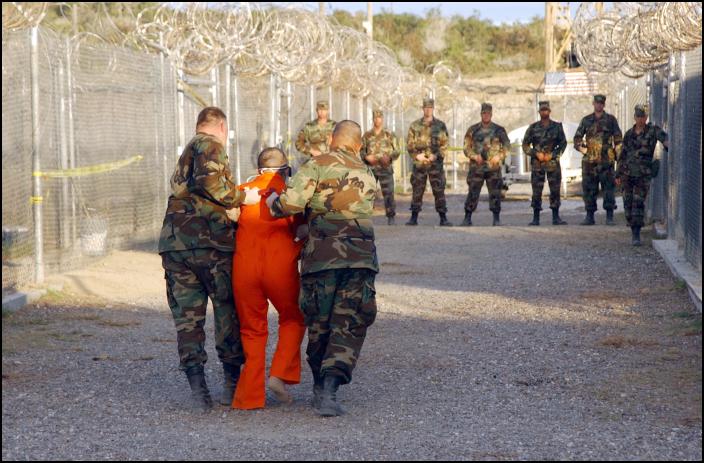

A Guantanamo detainee is escorted to his cell. (Wikimedia Commons)

When word leaked last week that advisers to President-elect Barack Obama were suggesting he create special national-security courts to try high-level Guantanamo detainees, a firestorm erupted among civil-rights advocates and lawyers who’ve represented prisoners there.

By the next day, the Obama camp had issued a statement backing away from the idea. Though Obama agreed that the Guantanamo Bay prison facility should be closed, there was “absolutely no truth to reports that a decision has been made about how and where to try the detainees,” said Denis McDonough, a senior Obama foreign-policy adviser, “and there is no process in place to make that decision until [Obama’s] national security and legal teams are assembled.”

Image has not been found. URL: http://www.washingtonindependent.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/scales-150x150.jpgIllustration by: Matt Mahurin

These days, there’s little question that the Guantanamo prison has become such a global symbol of American abuse that it must be closed. On the campaign trail, Obama specifically pledged to “close Guantanamo, reject the Military Commissions Act and adhere to the Geneva Conventions.”

But closing Guantanamo and ending the military commissions is the easy part. It’s what to do with the people imprisoned there that’s already presenting a thorny political problem for the new administration.

In voting for an amendment to the Military Commissions Act in 2006, Obama said it is “military courts, and not federal judges, who should make decisions on these detainees.”

Obama has never specified what he means by military courts, or how they would function differently than regular civilian courts. But law professors who’ve argued for military commissions or specialized courts say they would reduce the burden on the civilian court system and provide specialized judges knowledgeable about terrorism and handling classified information.

Equally important, some argue, is that it would allow for the prosecution of alleged terrorists for things that wouldn’t qualify as federal crimes under civilian criminal law, like group membership.

These courts would allow introduction of sensitive evidence against detainees provided by informants and other intelligence sources that the government wouldn’t want presented in an open civilian court, and might, depending on the particular rules, allow introduction of coerced evidence, or other evidence that “might not meet every jot and tittle of American criminal law,” as law professors Neal Katyal and Jack Goldsmith wrote in a New York Times op-ed on the subject last year.

Lawyers and organizations representing Guantanamo detainees, however, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights, Human Rights Watch and Human Rights First have called for trying suspected terrorists in the civilian federal court system, and oppose creating specialized courts. So have many law professors.

“I’m very much in favor of using the civilian system—regular federal courts based on criminal charges,” said George Fletcher, an expert in international criminal law at Columbia Law School. It would be dangerous in my view to create a whole new court.”

“From everything I can gather, there really is no need for it,” said American University Law Professor Herman Schwartz, talking about the national-security court proposal. “Classified information is not a serious problem,” he said, noting that the Classified Information Protection Act allows district court judges to delete or summarize classified information when necessary to protect state secrets. “They handle problems of large conspiracies, of evidence overseas. Most of the problems that might be raised have been handled quite well by federal court judges.”

Law professors from Harvard and Georgetown, however, who apparently have the ear of the Obama administration, have supported creating a special national-security court system.

Laurence Tribe, a Harvard law professor who is an Obama adviser, wrote in a 2002 Yale Law Journal article, with Neal Katyal, a Georgetown law professor, that specially created courts or commissions could be a wise idea — as long as they’re authorized by Congress and comport with the U.S. Constitution.

As Tribe told The Associated Press last week, in the story that’s ramped up the tension around this issue: “It would have to be some sort of hybrid that involves military commissions that actually administer justice rather than just serve as kangaroo courts.”

He and another Harvard law professor and close Obama advisor, Cass Sunstein, testified in December 2001 to the Senate Judiciary Committee that the creation of military commissions to try suspected terrorists of war crimes is perfectly legal.

Katyal, who represented Salim Hamdan, Osama Bin Laden’s driver, in a habeas corpus petition and before the U.S. military commission, and is reportedly offering advice to the Obama team, has more explicitly advocated for a national-security court system that would allow “preventive detention” — among the most controversial aspects of Bush administration detainee policy.

In a New York Times op-ed articlelast year, Katyal and Harvard Law Professor Jack Goldsmith advocated “a comprehensive system of preventive detention that is overseen by a national security court composed of federal judges with life tenure.”

Given the current sensitivity of the issue, Katyal, Tribe, Sunstein and Goldsmith all declined to be interviewed for this article.

The debate isn’t about all the approximately 250 detainees left at Guantanamo. Legal experts generally agree that many should be released, after the new administration internally assesses the evidence against them.

Donald Rumsfeld called the Gitmo detainees "the worst of the worst." (Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, though Defense. Sec. Donald Rumsfeld in 2002 called the Gitmo prisoners “the worst of the worst,” the Bush administration itself let about 500 of the 750 detained there go home, usually based on diplomatic arrangements with their home countries. Another 60 or so have been given clearance to leave, though the administration hasn’t figured out where to send them. Many could be in danger if they return to their home countries, and neither the U.S. nor other countries have offered to accept them.

The debate really centers around what to do with the few dozen people being held at Guantanamo that the Defense Dept. or CIA still believe are truly dangerous. This includes people like Khalid Sheikh Muhammad, an al Qaeda member who the 9/11 commission named “the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks.” He’s been charged with murder and war crimes. (Though the Bush administration has said it wants to try about 80 people before military commissions, so far only about 20 have been charged.)

No one wants to let him go free based on procedural technicalities, but it’s not clear at this point whether the evidence against him has been tainted by torture or involves sensitive classified information the government wouldn’t want him to see.

Obama has already pledged to shut down the existing military commissions. That leaves the civilian federal court system, where major crimes like terrorism, organized crime, drug offenses and other federal crimes are ordinarily tried.

Prisoners of war accused of war crimes, meanwhile, could be tried in the military justice system, though determining who qualifies as a prisoner of war in a “war on terror” will be problematic, given that Al Qaeda isn’t a country, and the “war on terror” isn’t really a war.

“Wars have beginnings, middles and ends,” said Schwartz, of American University. “They have battles. They have surrenders. This isn’t that. The two wars we’re in have very little to do with Al Qaeda.”

Equally dicey is that, under the laws of war, prisoners of war may be detained without charge until the end of hostilities, yet the “war on terror,” as defined by the Bush administration, has no apparent end.

Proponents of national-security courts say they could function as a hybrid between civilian courts and the military commissions already created, providing for temporary preventive detention, and exceptions to rules that normally grant the accused the right to see all the evidence against him, or to exclude evidence based on hearsay or obtained by coercion or torture.

The rules of criminal procedure that apply in federal district courts “go further than the Constitution requires,” said Benjamin Wittes, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of “Law and the Long War: The Future of Justice in the Age of Terror.” “You could alleviate some of the problems of these prosecutions and facilitate more trials if you streamline the rules.”

As the Yale law professor Ruth Wedgwood wrote in a 2001 op-edin The Wall Street Journal supporting the Bush-created military commissions: “U.S. Marines may have to burrow down into an Afghan cave to smoke out the leadership of Al Qaeda. It would be ludicrous to ask that they pause in the dark to pull an Afghan-language Miranda card from their kit bag. This is war, not a criminal case.”

But is it? Is it different than the war on drugs, for example? Are these cases really different than previous terrorism prosecutions, like those arising out of the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993, or the East African embassy bombings in 1998? And what are the consequences of creating special courts to get around the rules of evidence?

“National security courts are unnecessary and dangerous,” said Sharon Bradford Franklin, senior counsel at The Constitution Project. “The use of coerced evidence violates our constitutional safeguards provided by our traditional federal courts. Our courts have demonstrated they can handle these prosecutions.”

American University’s Schwartz agrees. “You shouldn’t be able to introduce evidence if it’s tainted by torture,” he said, “How reliable can it be? Khalid Sheik Mohammed, according that what he’s said, seems to have planned everything that’s ever happened going back to 1916. There’s something like 37 terrorist acts he’s supposedly confessed to. The thing about torture is you never know, because people will say anything.”

Mohammed has reportedly confessed to everything from the 9-11 attacks to personally beheading the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl to the attempted shoe bombing by Richard Reid to an attempt to assassinate Pope John Paul II.

Of course, excluding coerced confessions means some guilty people could be let go.

“A lot of the evidence produced in the military commissions was taken through torture,” said Candace Gorman, a Chicago-based lawyer who represents two prisoners at Guantanamo. “It might mean that men have to be let go that maybe we wouldn’t want to let go. But that’s the way the judicial system is structured.”

That could create real risks, though. What if some of those people are returned home, then join the ranks of those fighting against U.S. forces? The Pentagon claims that as many as three dozen former Guantanamo prisoners have taken up arms against Americans since their repatriation, although human rights groups say it’s closer to a handful, many of whom were radicalized by their experiences at Guantanamo.

Ultimately, it may be a more practical consideration that will drive the decision.

“I think Obama intends to act really quickly, to get prosecutions that result in the convictions of high-profile people,” said Scott Horton, an international lawyer and visiting professor at Hofstra Law School. “If he were to go for a national-security court, it would have to be done by legislation. That’s at least a year to set up a new commission.”

What’s more, any new commission would likely be attacked in the courts. “No matter what you do in a military commission there’s going to be a fight,” said Fletcher, of Columbia Law School, who assisted the Hamdan defense team during the military commission trial. “A clever lawyer can always defeat the government in a military commission case” by raising procedural objections, said Fletcher.

“My concern is that any new national-security court that might be devised is likely to contain the same sorts of unworkable procedures and problems that we see in the MCA,” said Joe McMillan, a Seattle lawyer who also worked on the Hamdan defense. “It’s just unnecessary. The civilian courts of the United States have dealt with terrorism cases and have at this point a better record of conviction than the military commissions.”

Indeed, the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay have only convicted 3 people so far (including one plea bargain and another in a trial boycotted by the accused), whereas the Justice Dept. has convicted 145 defendants in terrorism cases between Sept. 11, 2001 and the end of last year.

“We want the right to introduce evidence that a long tradition in our legal system has recognized is unreliable,” said McMillan, referring to evidence obtained under torture. “So we want to build a new court system to do that. I think we should resist that impulse.”

Hajra Shannon

Reviewer

Latest Articles

Popular Articles